Farm ponds are small (1 m 2 to approximately 0.05 km 2 ), shallow (< 8 m), natural or man-made surface depressions that permanently or temporarily hold water. They are frequently seen in agricultural regions in many countries(Yin and Shan, 2001; Céréghino et al., 2014; Grobicki et al., 2016). Owing to the low construction cost, high irrigation and drainage efficiency, and value for multiple uses, including drinking, fishing and washing, farm ponds have played an important role during the development of human civilization (Miller,2009; Mushet et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2018). In recent decades, however, the development of reservoir-based water systems has gradually weakened the importance of farm ponds in water supply. Many areas that were once farm ponds have been filled as a result of expanding urbanization (Huang et al., 2012;Hill et al., 2018) and agricultural intensification (Calhoun et al., 2014; Poschlod and Braun-Reichert, 2017) or have become isolated from one another due to the modification of ditches and streams (Fang et al., 2014). Thus, some obvious questions arise: Do farm ponds have functions beyond those of irrigation and water supply? Should they be conserved from contemporary degradation, and what are the challenges and solutions?

Conservation theory and practice pertaining to small, scattered wetlands(e.g., vernal pools, prairie potholes, farm ponds, gilgais, and cypress domes) was developed in the 1980s (Rashford et al., 2011; Raebel et al., 2012; Calhoun et al., 2014; Hunter et al., 2017). Several countries have implemented national conservation programs, including the Vernal Pool Association in the US, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment in France, and the Pond Action in England,in conjunction with transnational research collaborations, such as the European Pond Conservation Network (Reid et al., 2005; Biggs et al., 2010; Lassaletta et al., 2010). Along with numerous scientific papers, which have tripled in number over the last decade (source: Thomson Reuters’Web of Knowledge SM , October 2018), several reviews have highlighted farm ponds as regional biodiversity hotspots, providing habitats and refuges for some of the most endangered wetland plants, invertebrates and amphibians (Céréghino et al., 2014; Mushet et al., 2014; Hunter et al., 2017; Hill et al., 2018). Although developing countries require more effort to combat the increasing crisis of freshwater resource scarcity, most programs and findings have focused on developed countries(Liu and Yang, 2012; UN-Water, 2018). According to FAO (2013), a shortage of freshwater resources in terms of both quantity and quality will occur in 1/5 of the developing countries by 2030 due to high agricultural water consumption and severe nonpoint source pollution. Moreover, the predominance of small farms makes the ponds more important to agricultural activities (e.g., paddy planting, fish farming, and unfenced poultry and livestock breeding) and rural life in peripheral areas (Mitsuo et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2018b).These circumstances point to a need for targeted and systematic analyses of farm ponds in the developing countries.

China is the largest developing country with a total population of 1.4 billion,with approximately 42% of the population living in rural areas. China has faced historical challenges in the conflict between irrigation water demand and spatiotemporally heterogeneous precipitation. To mitigate water shortages and regulate the distribution of water resources, farm ponds were first constructed in Anhui Province early in the 700s BC, and then with the southward movement of agriculture during approximately the next thousand years, their prevalence extended from the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River to the Pearl River Delta and Yunnan Province (Yin and Shan, 2001; Zhang et al., 2009). After the foundation of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, farm ponds were vigorously developed and flourished as a unique natural-economic-social complex across southern China (Verhoeven et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2009;Yu et al., 2015). In recent decades, however, farm ponds, particularly small ponds, have faced a severe decline in numbers and malfunctions in terms of agricultural and ecological services. Although several nationwide environmental protection policies and legislations have been enacted to remedy water quality deterioration and water ecology degradation (e.g., the Water Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan issued by the Ministry of Environmental Protection in 2015, the Revised Water Pollution Prevention and Control Law issued by the National People's Congress in 2017, and the River/Lake Chief Mechanism issued by the General Office of the State Council in 2016),protection of farm ponds in upstream areas has been entirely ignored. Across China, there has been a lack of systematic effort to characterize, monitor, and assess the waters’environmental and ecological status (Fang et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2015). The lack of such efforts is mirrored in other developing countries in Eastern Europe, South Asia, and South America, where farm ponds are used extensively for agriculture, but are excluded in conservation programs for wetland ecosystems (Poschlod and Braun-Reichert, 2017; Hill et al., 2018).

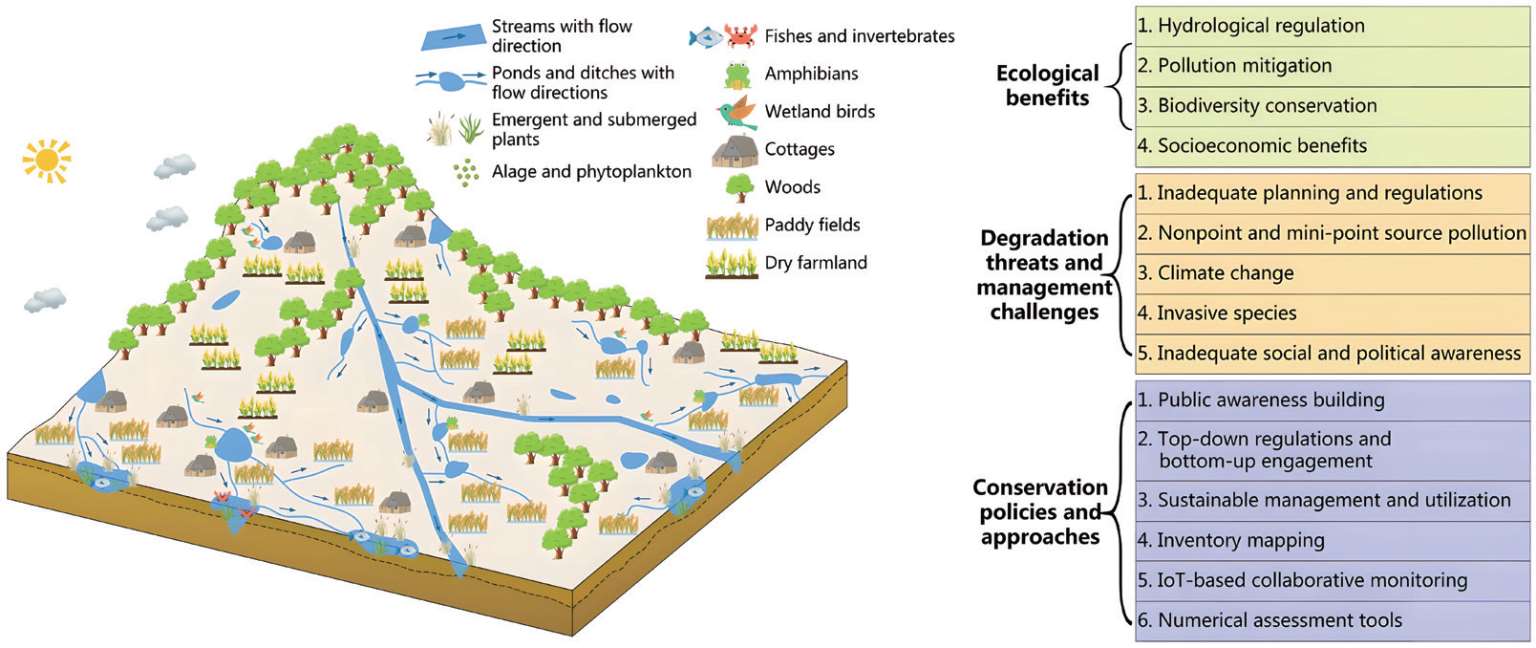

In view of the above scientific challenges and policy deficiencies, this study aims to analyze the ecosystem services, degradation threats, and conservation strategies associated with farm ponds in southern China (Fig. 2.1). Although these water bodies exist in other regions across China, they are ubiquitous in southern China owing to the humid subtropical climate and prevalence of paddy planting. After a historical and spatial overview (Section 2), the importance of farm ponds over scales ranging from within-pond to regional is explored by reviewing historical documents and recent literature (Section 3). Current threats and management challenges for farm ponds are then investigated in the Chinese context (Section 4), followed by a proposed conservation framework derived from, but not limited to, recognized policies and techniques used to manage similar wetland ecosystems (Section 5). This study provides the first synthetic perspective to assist policy-makers and researchers in understanding and restoring the environmental and ecological values of farm ponds in developing countries.

Fig. 2.1 Framework of farm pond perspective research of this chapter