外交本质上是一个政府间的沟通过程。

[136]

国际政治信号是传达信息的声明或行为,旨在影响接收者的发送者形象。从概念内涵上看,“信号”(signals)是行为体为了达到既定目的——改变对方的认知,而有意识地呈现出来的任何可观察的特征。

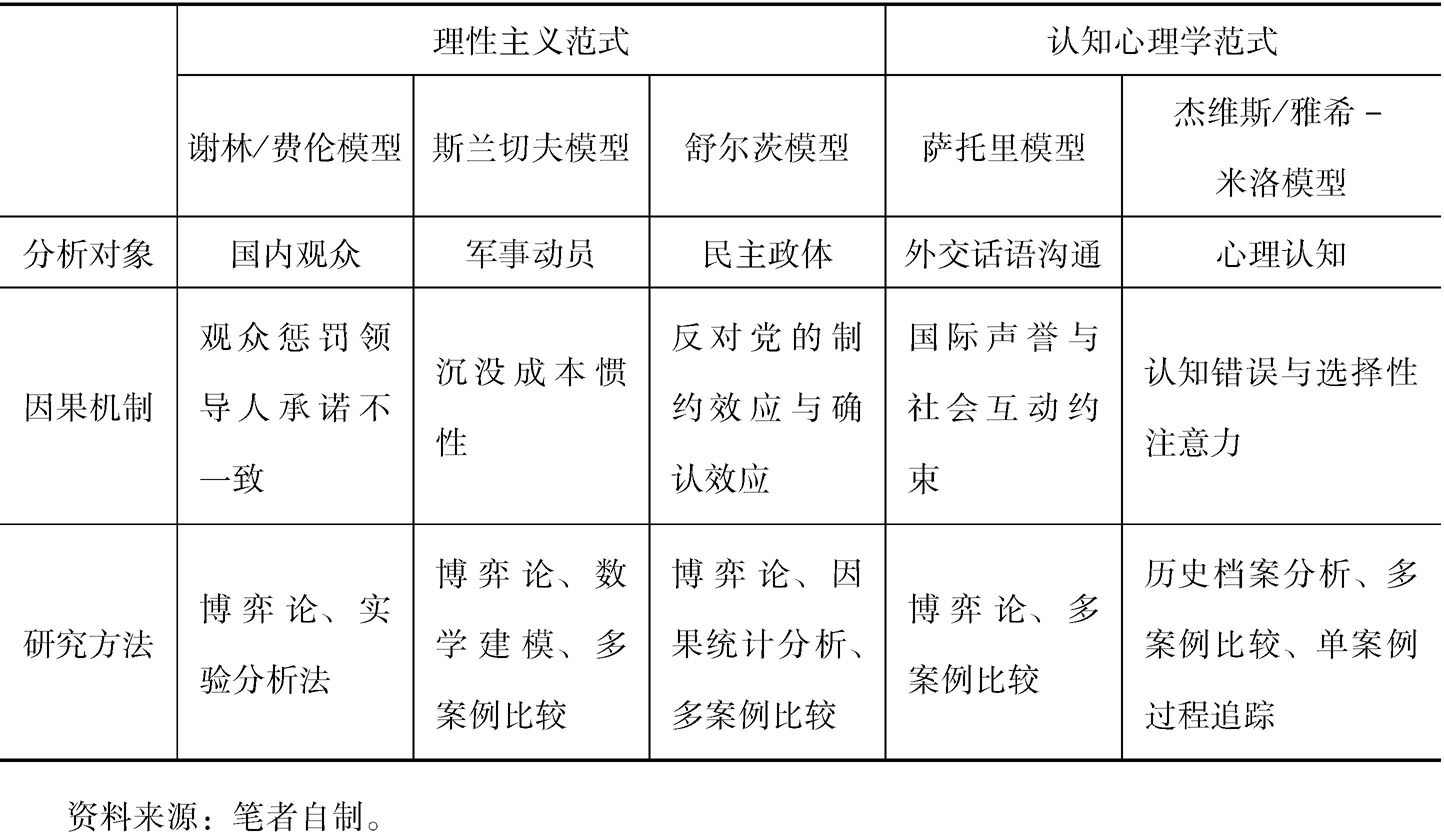

国际政治信号的潜在价值在于,它们能帮助推断内隐的意图,缓解信息不对称引发的信任困境。由于在缺乏约束力的情形下,国家通常很难说服对方。长期以来,围绕信息不对称所引发的意图识别难题,理性主义与认知心理学两大范式既相互批评又彼此竞争(参见表2-2)。

国际政治信号的潜在价值在于,它们能帮助推断内隐的意图,缓解信息不对称引发的信任困境。由于在缺乏约束力的情形下,国家通常很难说服对方。长期以来,围绕信息不对称所引发的意图识别难题,理性主义与认知心理学两大范式既相互批评又彼此竞争(参见表2-2)。

为评析国际政治信号理论的发展脉络,本章从学术争鸣角度以点带面地勾勒出丰富的信号理论谱系。观众成本理论是国际政治信号分析的焦点性议程,两大研究范式之间以及范式内部都对此有着大量学理辩论。以理性主义与认知心理学两大范式为架构,可梳理出五种主流的国际政治信号模型。对比理性主义范式下的谢林/费伦模型、舒尔茨模型与斯兰切夫模型,以及归纳认知心理学范式下的杰维斯/雅希-米洛模型与萨托里模型,有助于理解国际政治信号理论的演进脉络与逻辑得失,并为多元路径整合提供初步启示。理性主义范式下的三大国际政治信号模型,从成本—收益角度将国际政治信号特征界定为三方面:其一,可观察性,即一方面承诺/威胁需要被对方观测到,即合同法的“有效到达”;其二,不可逆性或违约代价巨大;其三,收益性。传递信号与相信他人信号的根本动力在于利益。不同的是,认知心理学范式关注国际政治信号的主观可信度感知,误解、偏见与心理定式会让昂贵成本信号失败。这种视野下的信号特征有:(1)主观性,不同行为体的信念、价值观与认知偏见,都会影响对同一个信号的不同解读;(2)动态性。没有不变的信号可信度逻辑,可信度受社会情境、注意力分配、情绪氛围等诸多因素影响,不同因素组合产生不同结果。

表2-2 国际政治信号分析的五大模型

在争鸣中两大研究范式对国际政治信号研究达成了一些基本共识:其一,信号是显示不可观察的意图的媒介。国际政治信号的价值在于,能帮助国家推断出内隐的不可观察的品质(意图、决心与类型等)。在自然界和人类社会中,信号发送与信号评估均普遍存在。 [137] 博弈论提供了一种形式化工具来研究在战略互动中如何发送和认知信号;但是无论是理性主义还是认知心理学研究都承认国际政治信号研究的意义,信号构成了外交互动与沟通的基础。

其二,昂贵成本只是信号可信的条件之一。经济学意义上的成本是物质投入与产出比率,但社会学意义上的成本是主观心理代价。某些信号从经济学角度看是廉价的,但从社会学角度看却是昂贵的。例如对于一个和平者而言,放弃进攻性武器将是代价廉价的行动,但是对于扩张主义者就不同了,若扩张主义者主动放下武器则是昂贵成本信号。

其三,国际政治信号传递与甄别不可分。孤立地研究信号传递与感知是片面的,行动者需要预测别人会做什么,别人也对它的行为做出预期。罗伯特·杰维斯主张既要关注国际关系中的信号传递逻辑,也要分析国际政治中的认知与误解。 [138] 因而需要更加综合性的逻辑框架,整合信号互动的两部分。

[1] “信息不对称”(asymmetic information)是指互动双方各自拥有对方所不知道的私有信息。或者说,某些博弈者拥有其他人不拥有的信息。参见A.Michael Spence,“Signaling in Retrospect and the Informational Structure of Markets”, American Economic Review ,Vol.92,No.1,2002,pp.434-459。

[2] James D.Fearon,“Signaling Foreign Policy Interests:Tying Hands Versus Sinking Costs”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.41,No.1,1997,pp.68-90.

[3] In-Koo Cho and David M.Kreps,“Signaling Games and Stable Equilibria”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics ,Vol.102,No.2,1987,pp.179-221.

[4] 国际政治信号理论的早期研究请参见Thomas C.Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict ,Cambridge,MA:Harvard University Press,1960;Thomas C.Schelling, Arms and Influence ,New Haven:Yale University Press,1966;Robert Jervis, The Logic of Images in International Relations ,New York:Columbia University Press,1970;Raymond Cohen, Theatre of Power : The Art of Diplomatic Signaling ,New York:Longman,1987。

[5] 尽管中国学者在研究案例和视角上带来了一些新理解和新观点,但整体上依然没能突破既有研究范式,中国视角的探索尚处于起步阶段。中国学者对国际政治信号研究的代表性文献有:蒲晓宇:《地位信号、多重观众与中国外交再定位》,《外交评论》2014年第2期;Xiaoyu Pu, Rebranding China : Contested Status Signaling in the Changing Global Order ,Stanford,California:Stanford University Press,2019;尹继武:《私有信息、外交沟通与中美危机升级》,《世界经济与政治》2020年第8期;漆海霞:《崛起信号、战略可信度与遏制战争》,《国际政治科学》2020年第4期。

[6] James Fearon,“Domestic Political Audiences and the Escalation of International Disputes”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.88,No.3,1994,pp.577-592;James Fearon,“Signaling Foreign Policy Interests:Tying Hands versus Sinking Costs”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.41,No.1,1997,pp.68-90.

[7] Jack Snyder and Erica Borghard,“The Cost of Empty Threats:A Penny,Not a Pound”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.105,No.3,2011,pp.437-456;Branislav Slantchev,“Politicians,the Media,and Domestic Audience Costs”, International Studies Quarterly ,Vol.50,No.2,2006,pp.445-477;Alastair Smith,“International Crises and Domestic Politics”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.92,No.3,1998,pp.623-638;Kenneth Schultz,“Looking for Audience Costs”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.45,No.1,2001,pp.32-60.

[8] 谢林在《冲突的战略》一书中指出“烧毁桥梁”“扔掉方向盘”等看起来自断后路的行动,是主动放弃自由选择增加可信度的做法,这与费伦模型的“捆绑双手”逻辑一致。参见Thomas C.Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict ,Cambridge,MA:Harvard University Press,1960;James D.Fearon,“Signaling Foreign Policy Interests:Tying Hands versus Sinking Costs”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.41,No.1,1997,pp.68-90。

[9] 美国政治学学者巴里·温加斯特(Barry R.Weingast)对此进行了系统分析,政治学文献也将可信承诺问题称为“温加斯特困境” (Weingast's Dilemma)。参见Barry R.Weingast,“The Political Foundations of Limited Government:Parliament and Sovereign Debt in 17th-and 18th-Century England”,in John N.Drobak and John V.C.Nye eds., The Frontiers of the New Institutional Economics ,San Diego:Academic Press,1997,pp.213-246;Douglass C.North and Barry R.Weingast,“Constitutions and Commitment:The Evolution of Institutions Governing Public Choice in Seventeenth-Century England”, Journal of Economic History ,Vol.49,No.4,1989,pp.803-832;Kenneth Shepsle,“Discretion,Institutions,and the Problem of Government Commitment”,in Pierre Bourdieu and James Coleman eds., Social Theory for a Changing Society ,Boulder:Westview Press,1991,pp.245-263。

[10] Brandon C.Prins,“Institutional Instability and the Credibility of Audience Costs:Political Participation and Interstate Crisis Bargaining,1816-1992”, Journal of Peace Research ,Vol.40,No.1,2003,pp.67-84.

[11] Beth A.Simmons and Allison Danner,“Credible Commitments and the International Criminal Court”, International Organization ,Vol.64,No.2,2010,pp.225-256.

[12] 一个典型的例子就是“烧桥”行动,即面对大军压境之时自断后路,烧掉逃生的唯一桥梁,这种主动限制选择范围的昂贵做法不仅能够激发背水一战的斗志,而且向对方传递出强烈的决心信号。参见Thomas C.Schelling,“Essay on Bargaining”, American Economic Revie w,Vol.46,No.3,1956,pp.281-306;Thomas C.Schelling,“The Strategy of Conflict:Prospectus for a Reorientation of Game Theory”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.2,No.3,1958,pp.203-264。

[13] James Fearon,“Domestic Political Audiences and the Escalation of International Disputes”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.88,No.3,1994,pp.577-592;James Fearon,“Signaling Foreign Policy Interests:Tying Hands versus Sinking Costs”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.41,No.1,1997,pp.68-90.

[14] Michael Tomz,“Domestic Audience Costs in International Relations:An Experimental Approach”, International Organization ,Vol.61,No.4,2007,p.821;William G.Nomikos and Nicholas Sambanis,“What is The Mechanism Underlying Audience Costs?Incompetence,Belligerence,and Inconsistency”, Journal of Peace Research ,Vol.56,No.4,2019,pp.575-588.

[15] James D.Fearon,“Domestic Political Audiences and the Escalation of International Disputes”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.88,No.3,1994,p.577.

[16] James D.Fearon,“Signaling versus the Balance of Power and Interests:An Empirical Test of a Crisis Bargaining Model”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.38,No.2,1994,pp.236-269;James Fearon,“Rationalist Explanations for War”, International Organization ,Vol.49,No.3,1995,pp.379-414;James Fearon,“Signaling Foreign Policy Interests:Tying Hands versus Sinking Costs”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.41,No.1,1997,pp.68-90.

[17] James D.Fearon,“Rationalist Explanations for War”, International Organization ,Vol.49,No.3,1995,pp.379-414;Robert Powell,“Bargaining Theory and International Conflict”, Annual Review of Political Science ,Vol.5,2002,pp.1-30;Robert Powell,“War as a Commitment Problem”, International Organization ,Vol.60,No.1,2006,pp.169-203.

[18] James D.Fearon,“Domestic Political Audiences and the Escalation of International Disputes”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.88,No.3,1994,p.577.

[19] James D.Morrow,“Capabilities,Uncertainty,and Resolve:A Limited Information Model of Crisis Bargaining”, American Journal of Political Science ,Vol.33,No.4,Nov.,1989,pp.941-972;Mark Fey and Kristopher W.Ramsay,“Uncertainty and Incentives in Crisis Bargaining:Game-Free Analysis of International Conflict”, American Journal of Political Science ,Vol.55,No.1,2011,pp.149-169.

[20] James D.Morrow,“Alliances,Credibility,and Peacetime Costs”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.38,No.2,1994,pp.270-297;Alastair Smith,“Alliance Formation and War”, International Studies Quarterly ,Vol.39,No.4,1995,pp.405-425;Alastair Smith,“Extended Deterrence and Alliance Formation”, International Interaction s,Vol.24,No.4,1998,pp.315-343.

[21] James D.Morrow,“The Strategic Setting of Choices:Signaling,Commitments,and Negotiation in International Politics”,in David A.Lake and Robert Powell eds., Strategic Choice and International Relations ,Princeton:Princeton University Press,1999,p.87.

[22] Robert Jervis, How Statesmen Think : The Psychology of International Politics ,Princeton:Princeton University Press,2017,pp.114-115.

[23] James G.March and Johan P.Olsen,“The Institutional Dynamics of International Political Order”, International Organization ,Vol.52,No.4,1998,pp.943-969;Robert Nalbandov,“Battle of Two Logics:Appropriateness and Consequentiality in Russian Interventions in Georgia”, Caucasian Review of International Affairs ,Vol.3,No.1,2009,pp.20-36.

[24] Erik Gartzke,“War is in the Error Term”, International Organization ,Vol.53,No.3,1999,p.570.

[25] Marc Trachtenberg,“Audience Costs:An Historical Analysis”, Security Studies ,Vol.21,No.1,2012,pp.37-40.

[26] Joshua D.Kertzer,Ryan Brutger,“Decomposing Audience Costs:Bringing the Audience Back into Audience Cost Theory”, American Journal of Political Science ,Vol.60,No.1,2016,pp.234-249.

[27] Jack S.Levy,Michael K.McKoy,Paul Poast and Geoffrey P.R.Wallace,“Backing Out or Backing in?Commitment and Consistency in Audience Costs Theory”, American Journal of Political Science ,Vol.59,No.4,2015,pp.988-1001.

[28] Kai Quek and Alastair Iain Johnston,“Can China Back Down?Crisis De-escalation in the Shadow of Popular Opposition”, International Security ,Vol.42,No.3,2017/2018,pp.7-36.

[29] Brian C.Rathbun, Diplomacy's Value : Creating Security in 1920s Europe and the Contemporary Middle East ,Ithca:Cornell University Press,2014,pp.8-19.

[30] Joshua D.Kertzer,Brian C.Rathbun and Nina Srinivasan Rathbun,“The Price of Peace:Motivated Reasoning and Costly Signaling in International Relations”, International Organization ,Vol.74,No.1,2020,pp.95-118;Ole R.Holsti and James N.Rosenau,“The Domestic and Foreign Policy Beliefs of American Leaders”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.32,No.2,1988,pp.248-294.

[31] 有研究指出,尼克松对华关系解冻的动机在于重塑国内观众偏好、获得国内观众奖赏。参见尹继武、李宏洲《观众奖赏、损失框定与关系解冻的起源——尼克松对华关系缓和的动力机制及其战略竞争管控启示》,《当代亚太》2020年第4期;Matthew S.Levendusky and Michael C.Horowitz,“When Backing Down is the Right Decision:Partisanship,New Information,and Audience Costs”, Journal of Politics ,Vol.74,No.2,2012,pp.323-338;Robert Trager and Lynn Vavreck,“The Political Costs of Crisis Bargaining:Presidential Rhetoric and the Role of Party”, American Journal of Political Science ,Vol.55,No.3,2011,pp.526-545。

[32] Robert F.Trager and Lynn Vavreck,“The Political Costs of Crisis Bargaining:Presidential Rhetoric and the Role of Party”, American Journal of Political Science ,Vol.55,No.3,2011,pp.526-545;Anne E.Sartori,“A Reputational Theory of Diplomacy”,in Anne E.Sartori, Deterrence by Diplomacy ,Princeton University Press,2005,pp.43-46.

[33] Jack Snyder and Eerica D.Borghard,“The Cost of Empty Threats:A Penny,Not a Pound”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.105,No.3,2011,pp.437-456.

[34] Daniele L.Lupton,“Signaling Resolve:Leaders,Reputations,and the Importance of Early Interactions”, International Interactions ,Vol.44,No.1,2018,p.64.

[35] Joe Eyerman and Robert A.Hart Jr.,“An Empirical Test of the Audience Cost Proposition:Democracy Speaks Louder than Words”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.40,No.4,1996,pp.597-616;Bruce Bueno de Mesquita,James D.Morow,Randolph M.Siverson and Alastair Smith,“An Institutional Explanation for the Democratic Peace”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.93,No.4,1999,pp.791-807;Branislav L.Slantchev,“Audience Cost Theory and Its Audiences”, Security Studies ,Vol.21,No.3,2012,p.379.

[36] Keren Tenenboim-Weinblat et al.,“Beyond Peace Journalism:Reclasifying Conflict Naratives in the Israeli News Media”, Journal of Peace Research ,Vol.53,No.2,2016,pp.151-165.

[37] Marc Trachtenberg,“Audience Costs:An Historical Analysis”, Security Studies ,Vol.21,No.1,2012,pp.37-40.

[38] Sarah Burns and Andrew Stravers,“Obama,Congress,and Audience Costs:Shifting the Blame on the Red Line”, Political Science Quarterly ,Vol.135,No.1,2020,pp.67-101;William G.Nomikos and Nicholas Sambanis,“What is The Mechanism Underlying Audience Costs?Incompetence,Belligerence,and Inconsistency”, Journal of Peace Research ,Vol.56,No.4,2019,pp.575-588.

[39] 蒲晓宇:《地位信号、多重观众与中国外交再定位》,《外交评论》2014年第2期;Xiaoyu Pu, Rebranding China : Contested Status Signaling in the Changing Global Order ,Stanford,California:Stanford University Press,2019,pp.70-85.

[40] Branislav L.Slantchev, Military Threats : The Costs of Coercion and the Price of Peace ,Cambridge,UK:Cambridge University Press,2011,p.4.

[41] Branislav L.Slantchev,“Military Coercion in Interstate Crises”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.99,No.4,2005,pp.533-547.

[42] Branislav L.Slantchev,“Military Coercion in Interstate Crises”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.99,No.4,2005,pp.533-547;Branislav L.Slantchev,“Audience Cost Theory and Its Audiences”, Security Studies ,Vol.21,No.3,2012,pp.376-382.

[43] Jack Snyder and Erica D.Borghard,“The Cost of Empty Threats:A Penny,Not a Pound”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.105,No.3,2011,pp.437-456.

[44] Branislav L.Slantchev, Military Threats : The Costs of Coercion and the Price of Peace ,New York:Cambridge University Press,2011,p.150.

[45] Branislav L.Slantchev,“Military Coercion in Interstate Crises”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.99,No.4,2005,p.533.

[46] Kai Quek,“Type Ⅱ Audience Costs”, Journal of Politics ,Vol.79,No.4,2017,p.1440.

[47] James D.Morrow,“Alliances:Why Write Them Down?” Annual Review of Political Science ,Vol.3,2000,pp.63-83;Brett Ashley Leeds,“Alliance Reliability in Times of War:Explaining State Decisions to Violate Treaties”, International Organization ,Vol.57,No.4,2003,pp.801-827;Brett Ashley Leeds,“Do Alliances Deter Aggression?The Influence of Military Alliances on the Initiation of Militarized Interstate Disputes”, American Journal of Political Science ,Vol.47,No.3,2003,pp.427-439.

[48] Branislav L.Slantchev, Military Threats : The Costs of Coercion and the Price of Peace ,p.4.

[49] Branislav L.Slantchev, Military Threats : The Costs of Coercion and the Price of Peace ,p.250.

[50] Branislav L.Slantchev,“Military Coercion in Interstate Crises”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.99,No.4,2005,p.533.

[51] 当然长时间保持较高的战备状态也可能导致疲劳,随之而来的是令人惊讶的风险。参见Branislav L.Slantchev, Military Threats : The Costs of Coercion and the Price of Peace ,p.77。

[52] Branislav L.Slantchev, Military Threats : The Costs of Coercion and the Price of Peace ,pp.116-118.

[53] Branislav L.Slantchev, Military Threats : The Costs of Coercion and the Price of Peace ,pp.124-132.

[54] Branislav L.Slantchev,“Military Coercion in Interstate Crises”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.99,No.4,2005,p.533.

[55] Kai Quek,“Type Ⅱ Audience Costs”, Journal of Politics ,Vol.79,No.4,2017,pp.1438-1443.

[56] Kai Quek,“Four Costly Signaling Mechanisms”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.115,No.2,2021,pp.540-542.

[57] Brian Lai,“The Effects of Different Types of Military Mobilization on the Outcome of International Crises”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.48,No.2,2004,pp.211-229.

[58] Branislav L.Slantchev, Military Threats : The Costs of Coercion and the Price of Peace ,pp.79-80.

[59] Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky,“Prospect Theory:An Analysis of Decision under Risk”, Econometric ,Vol.47,No.2,1979,pp.263-292;国际关系的前景理论分析参见Jack S.Levy,“Prospect Theory,Rational Choice,and International Relations”, International Studies Quarterly ,Vol.41,No.1,1997,pp.87-112。

[60] Daniel Friedman et.al.,“Searching for the Sunk Cost Fallacy”, Experimental Economics ,Vol.10,No.1,2007,pp.79-104.

[61] Nick Benschop et.al.,“Construal Level Theory and Escalation of Commitment”, Theory and Decision ,Vol.91,No.1,2021,pp.135-151;Hal Richard Arkes and Catherine Blumer,“The Psychology of Sunk Cost”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes ,Vol.35,No.1,1985,pp.124-140.

[62] Jack Snyder and Erica Borghard,“The Cost of Empty Threats:A Penny,Not a Pound”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.105,No.3,2011,pp.437-456;Joshua D.Kertzer and Ryan Brutger,“Decomposing Audience Costs:Bringing the Audience:Back into Audience Cost Theory”, American Journal of Political Science ,Vol.60,No.1,2016,pp.234-249.

[63] Clayton L.Thyne, How International Relations Affect Civil Conflict : Cheap Signals,Costly Consequences ,New York:Lexington Books,p.45.

[64] Bernardo Teles Fazendeiro,“Keeping a Promise:Roles,Audiences and Credibility in International Relations”, International Relation ,Vol.35,No.2,2021,pp.299-319.

[65] Kenneth Schultz, Democracy and Coercive Diplomacy ,Cambridge,UK:Cambridge University Press,2004,pp.63-66.

[66] Kenneth Schultz, Democracy and Coercive Diplomacy ,Cambridge,UK:Cambridge University Press,2004,pp.118-119.

[67] Branislav L.Slantchev,“Politicians,the Media,and Domestic Audience Costs”, International Studies Quarterly ,Vol.50,No.2,2006,pp.445-477.

[68] Miriam Fendius Elman,“Unpacking Democracy:Presidentialism,Parliamentarism,and Theories of Democratic Peace”, Security Studies ,Vol.9,No.4,2000,pp.91-126.

[69] Joe Clare,“Domestic Audiences and Strategic Interests”, Journal of Politics ,Vol.69,No.3,2007,pp.735-737;Alexander B.Downes and Todd S.Sechser,“The Illusion of Democratic Credibility”, International Organization ,Vol.66,No.3,2012,p.485;Jack Snyder and Erica D.Borghard,“The Cost of Empty Threats:A Penny,Not a Pound”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.105,No.3,2011,pp.439-441;Marc Trachtenberg,“Audience Costs:An Historical Analysis”, Security Studies ,Vol.21,No.1,2012,pp.37,39-40.

[70] Kenneth A.Schultz,“Do Democratic Institutions Constrain or Inform?Contrasting Two Institutional Perspectives on Democracy and War”, International Organization ,Vol.53,No.2,1999,pp.233-266;Kenneth A.Schultz, Democracy and Coercive Diplomacy ,Cambridge,UK.:Cambridge University Press,2001;Kenneth A.Schultz,“Domestic Opposition and Signaling in International Crises”, American Political Science Association ,Vol.92,No.4,1998,pp.829-844;David Kinsella,Bruce Russett,“Conflict Emergence and Escalation in Interactive International Dyads”, Journal of Politics ,Vol.64,No.4,2002,pp.1045-1068;Brandon J.Kinne,Nikolay Marinov,“Electoral Authoritarianism and Credible Signaling in International Crises”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.57,No.3,2013,pp.359-386.

[71] John J.Mearsheimer, Why Leaders Lie : The Truth About Lying in International Politics ,Oxford:Oxford University Press,2011,p.16.

[72] 参见Brian C.Rathbun, Trust in International Cooperation : International Security Institutions,Domestic Politics and American Multilateralism ,Cambridge,UK:Cambridge University Press,2012。

[73] Branislav L.Slantchev,“Politicians,the Media,and Domestic Audience Costs”, International Studies Quarterly ,Vol.50,No.2,2006,pp.445-477;Jessica L.Weeks,“Autocratic Audience Costs:Regime Type and Signaling Resolve”, International Organization ,Vol.62,No.1,2008,pp.35-36.

[74] Jessica Chen Weiss,“Authoritarian Signaling,Mass Audiences,and Nationalist Protest in China”, International Organization ,Vol.67,No.1,2013,pp.1-35.

[75] Alexander B.Downes and Todd S.Sechser,“The Illusion of Democratic Credibility”, International Organization ,Vol.66,No.3,2012,pp.457-489.

[76] James A.Stimson, Public Opinion in America : Moods,Cycles,and Swings ,Boulder,CO:Westview Press,1991,pp.2-8.

[77] Branislav L.Slantchev,“Politicians,the Media,and Domestic Audience Costs”, International Studies Quarterly ,Vol.50,No.2,2006,p.451.

[78] Joe Eyerman,Robert A.Hart and Jr.,“An Empirical Test of the Audience Cost Proposition:Democracy Speaks Louder than Words”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.40,No.4,1996,pp.597-616.

[79] Joe Clare,“Domestic Audiences and Strategic Interests”, The Journal of Politics ,Vol.69,No.3,2007,pp.732-745.

[80] Michael Colaresi,“A Boom with Review:How Retrospective Oversight Increases the Foreign Policy Ability of Democracies”, American Journal of Political Science ,Vol.56,No.3,2012,pp.671-689.

[81] Robert Jervis, The Logic of Images in International Relations ,p.6.

[82] O.R.Holsti,“The Belief System and National Images:A Case Study”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.6,No.3,1962,pp.244-252;O.R.Holsti,“Cognitive Dynamics and Images of the Enemy”, Journal of International Affairs ,Vol.21,No.1,1967,pp.16-39;O.R.Holsti,“Cognitive Process Approaches to Decision-making:Foreign Policy Actors Viewed Psychologically”, American Behavioral Scientist ,Vol.20,No.1,1970,pp.11-32;Arthur A.Stein,“When Misperception Matters”, World Politics ,Vol.34,No.4,1982,pp.505-526.

[83] Keren Yarhi-Milo, Knowing the Adversary : Leaders,Intelligence,and Assessment of Intentions in International Relations ,pp.1-20.

[84] Thomas C.Schelling, Arms and Influence ,p.150.

[85] Dustin H.Tingley and Barbara F.Walter,“The Effect of Repeated Play on Reputation Building:An Experimental Approach”, International Organization ,Vol.65,No.2,2011,pp.343-365.

[86] Robert Jervis, The Logic of Images in International Relations ,p.20.

[87] Dustin Tingley and Barbara Walter,“Can Cheap Talk Deter?An Experimental Analysis”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.55,No.6,2011,pp.996-1020.

[88] Anne E.Sartori, Deterrence by Diplomacy ,Princeton,N.J.:Princeton University Press,2007;Robert F.Trager,“Diplomatic Calculus in Anarchy:How Communication Matters”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.104,No.2,2010,pp.347-368;Alexandra Guisinger and Alastair Smith,“Honest Threats:The Interaction of Reputation and Political Institutions in International Crises”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.46,No.2,2002,pp.175-200;Shuhei Kurizaki,“Efficient Secrecy:Public versus Private Threats in Crisis Diplomacy”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.101,No.3,2007,p.543.

[89] Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler,“When Corrections Fail:The Persistence of Political Misperceptions”, Political Behavior ,Vol.32,No.2,2010,pp.303-330.

[90] Yaacov Vertzberger, The World in Their Minds : Information Processing,Cognition,and Perception in Foreign Policy ,Stanford,California:Stanford University Press,1990,p.17.

[91] Keren Yarhi-Milo, Knowing the Adversary : Leaders,Intelligence,and Assessment of Intentions in International Relations ,pp.1-20.

[92] Yaacov Vertzberger, The World in Their Minds : Information Processing,Cognition,and Perception in Foreign Policy ,p.17.

[93] Charles S.Taber and Milton Lodge,“Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs”, American Journal of Political Science ,Vol.50,No.3,2006,pp.755-769.

[94] Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler,“When Corrections Fail:The Persistence of Political Misperceptions”, Political Behavior ,Vol.32,No.2,2010,p.307.

[95] Gerd Gigerenzer,“Why Heuristics Work”, Perspectives on Psychological Science ,Vol.3,No.1,2008,pp.20-29.

[96] Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber,“Why Do Humans Reason?Arguments for an Argumentative Theory”, Behavioral and Brain Sciences ,Vol.34,No.2,2011,pp.57-111.

[97] Keren Yarhi-Milo, Knowing the Adversary : Leaders,Intelligence,and Assessment of Intentions in International Relations ,pp.4-19.

[98] 公众舆论有时可以被操纵,至少看起来会限制政府的选择,这种情况可以被利用来实现外交政策的目的。Fraser Harbutt, Yalta 1945 : Europe and America at the Crossroads ,Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,2010,pp.310-330;Fraser Harbutt, The Iron Curtain : Churchill,America and the Origins of the Cold War ,Oxford:Oxford University Press,1986,pp.86-92。

[99] Todd H.Hall, Emotional Diplomacy : Official Emotion on the International Stage ,Ithaca,NY:Cornell University Press,2015,p.10.

[100] Paul R.Brewer,“Value Words and Lizard Brains:Do Citizens Deliberate About Appeals to Their Core Values?” Political Psychology ,Vol.22,No.1,2001,pp.45-64;James N.Druckman,“On the Limits of Framing Effects:Who Can Frame?” Journal of Politics ,Vol.63,No.4,2001,pp.1041-1066.

[101] Brian C.Rathbun,Joshua D.Kertzer,Jason Reifler,Paul Goren and Thomas J.Scotto,“Taking Foreign Policy Personally:Personal Values and Foreign Policy Attitudes”, International Studies Quarterly ,Vol.60,No.1,2016,pp.124-137;Brian C.Rathbun,“Hierarchy and Community at Home and Abroad:Evidence of a Common Structure of Domestic and Foreign Policy Beliefs in American Elites”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.51,No.3,2007,pp.379-407.

[102] Ryan Brutger and Joshua D.Kertzer,“A Dispositional Theory of Reputation Costs”, International Organization ,Vol.72,No.3,2018,pp.693-724;Charles F.Hermann,“Changing Course:When Governments Choose to Redirect Foreign Policy”, International Studies Quarterly ,Vol.34,No.1,1990,pp.3-21.

[103] Keren Yarhi-Milo, Knowing the Adversary : Leaders,Intelligence,and Assessments of Intentions in International Relations ,pp.18-20.

[104] Ryan Brutger,“The Power of Compromise Proposal Power,Partisanship,and Public Support in International Bargaining”, World Politics ,Vol.73,No.1,2021,pp.128-166.

[105] Jeong-Yoo Kim,“Cheap Talk and Reputation in Repeated Pretrial Negotiation”, The RAND Journal of Economics ,Vol.27,No.4,1996,pp.787-802;James Johnson,“Is Talk Really Cheap?Prompting Conversation Between Critical Theory and Rational Choice”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.87,No.1,1993,pp.74-86.

[106] Azusa Katagir and Eric Min,“The Credibility of Public and Private Signals:A Document-Based Approach”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.113,No.1,2019,pp.156-172.

[107] James Johnson,“Is Talk Really Cheap:Prompting Conversation Between Critical Theory and Rational Choice”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.87,No.1,1993,pp.74-86.

[108] Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler,“When Corrections Fail:The Persistence of Political Misperceptions”, Political Behavior ,Vol.32,No.2,2010,pp.303-330.

[109] Ann E.Sartor,“The Might of the Pen:A Reputational Theory of Communication in International Disputes”, International Organization ,Vol.56,No.1,2002,pp.121-149.

[110] Anne Sartori, Deterrence by Diplomacy ,p.6.

[111] James Johnson,“Is Talk Really Cheap:Prompting Conversation Between Critical Theory and Rational Choice”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.87,No.1,1993,pp.74-86.

[112] 参见Anne E.Sartori, Deterrence by Diplomacy ,Princeton:Princeton University Press,2005;Robert F.Trager, Diplomacy : Communication and the Origins of International Order ,Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,2017。

[113] Jennifer Wolak, Compromise in an Age of Party Polarization ,New York:Oxford University Press,2020,p.10.

[114] Anne E.Sartori,“The Might of the Pen:A Reputational Theory of Communication in International Disputes”, International Organization ,Vol.56,No.1,2002,pp.121-149.

[115] Alexandra Guisinger and Alastair Smith,“Honest Threats:The Interaction of Reputation and Political Institutions in International Crises”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.46,No.2,2002,pp.175-200.

[116] Marion Just and Anne Crigler,“Leadership Image-Building:After Clinton and Watergate”, Political Psychology ,Vol.21,No.1,2000,pp.179-198.

[117]

Michael Tomz,“Domestic Audience Costs inInternational Relations:An Experimental Approach”,

International Organization

,Vol.61,No.4,2007,pp.821-840;Jack S.Levy,Michael K.McKoy,Paul Poast and Geoffrey P.R.Wallace,“Backing Out or Backing in?Commitment and Consistency in Audience Costs Theory”,

American Journal of Political Science

,Vol.59,No.4,2015,pp.988-1001;Ahmer Tarar and Bahar

,“Public Commitment in Crisis Bargaining”,

International Studies Quarterly

,Vol.53,No.3,2009,pp.817-839.

,“Public Commitment in Crisis Bargaining”,

International Studies Quarterly

,Vol.53,No.3,2009,pp.817-839.

[118] Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and David Lalman, War and Reason : Domestic and International Imperatives ,New Haven:Yale University Press,1992,pp.10-30.

[119] Matthew Baum,“Going Private:Public Opinion,Presidential Rhetoric,and the Domestic Politics of Audience Costs in U.S.Foreign Policy Crises”, Journal of Conflict Resolution ,Vol.48,No.5,2004,pp.603-631;James Meernik and Michael Ault,“Public Opinion and Support for U.S.Presidents’ Foreign Policies”, American Politics Research ,Vol.29,No.4,2001,pp.352-373.

[120] Clayton L.Thyne, How International Relations Affect Civil Conflict : Cheap Signals,Costly Consequences ,New York:Lexington Books,2009,p.75.

[121] Eric Gartzke and Yonatan Lupu,“Still Looking for Audience Costs”, Security Studies ,Vol.21,No.3,2012,pp.391-397;Marc Trachtenburg,“Audience Costs:An Historical Analysis”, Security Studies ,Vol.21,No.1,2012,pp.3-42.

[122] Jelena Suboti,“Narrative,Ontological Security,and Foreign Policy Change”, Foreign Policy Analysis ,Vol.12,No.4,2016,pp.616-617.

[123] Thomas E.Nelson,Zoe M.Oxley and Rosalee A.Clawson,“Toward a Psychology of Framing Effects”, Political Behavior ,Vol.19,No.3,1997,pp.221-246.

[124] James N.Druckman,“Political Preference Formation:Competition,Deliberation,and the (Ir)relevance of Framing Effects”, American Political Science Review ,Vol.98,No.4,2004,pp.671-686.

[125] Ronald R.Krebs and Patrick Thaddeus Jackson,“Twisting Tongues and Twisting Arms:The Power of Political Rhetoric”, European Journal of International Relations ,Vol.13,No.1,2007,pp.38-41;Neta Crawford, Argument and Change in World Politics : Ethics,Decolonization,and Humanitarian Intervention ,Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,2002,pp.26-27;Frank Schimmelfennig, The EU,NATO and the Integration of Europe : Rules and Rhetoric ,New York:Cambridge University Press,2003,pp.220-227.

[126] Margaret E.Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, Activists beyond Borders : Advocacy Networks in International Politics ,Ithaca:Cornell University Press,1998,pp.28-29.

[127] Lesley Wexler,“The International Deployment of Shame,Second-Best Responses and Norm Entrepreneurship:The Campaign to Ban Landmines and the Landmine Ban Treaty”, Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law ,Vol.20,No.3,2003,p.567.

[128] Thomas Risse and Stephen C.Ropp,“International Human Rights Norms and Domestic Change:Conclusions”,in Thomas Risse,Stephen C.Ropp,and Kathryn Sikkink eds., The Power of Human Rights : International Norms and Domestic Change ,Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,1999,p.252.

[129] Emilie M.Hafner-Burton,“Sticks and Stones:Naming and Shaming the Human Rights Enforcement Problem”, International Organization ,Vol.62,No.42008,pp.689-716;Jacqueline H.R.DeMeritt,“International Organizations and Government Killing:Does Naming and Shaming Save Lives?” International Interactions ,Vol.38,No.5,2012,pp.597-621;Matthew Krain,“J’accuse!Does Naming and Shaming Perpetrators Reduce the Severity of Genocides or Politicides?” International Studies Quarterly ,Vol.56,No.3,2012,pp.574-589.

[130] 从词源上看,“污名”是来自希腊语,其最初含义是指一种文身或动物皮上切割或烧伤的痕迹。在现代用法中,污名常常与个体被疏远、孤立有关,特别是在公共场合,被疏远的个体常被认为是“离经叛道”或有“道德污点”。污名化过程主要有:标签(标记差异)、刻板印象(负面印象),认知区隔(区别他我),地位丧失(社会贬低、自我贬低)和歧视(社会排斥)。阿尔弗雷德·齐默恩(Alfred Zimmern)在1936年发表的《国际联盟与法治》是最早提出“羞耻动员”的学术文献之一。参见Alfred Zimmern, The League of Nations and The Rule of Law 1918-1935 ,London:Macmillan,1936,pp.459-460。

[131] Rebecca Adler-Nissen,“Stigma Management in International Relations:Transgressive Identities,Norms,and Order in International Society”, International Organization,Vol.68,No.1,2014,pp.143-176.

[132] Thomas Risse and Kathryn Sikkink,“Conclusions” in Thomas Risse,Stephen C.Ropp and Kathryn Sikkink eds., The Persistent Power of Human Rights : From Commitment to Compliance ,pp.275-295.

[133] T.Ann Dugan, With Words,Not Weapons : Personal Diplomacy in U.S .- Soviet Relations at the End of the Cold War ,2000,pp.3-10;Robert F.Trager,“Diplomatic Signaling among Multiple States”, The Journal of Politics ,Vol.77,No.3,2015,pp.635-647;Howard Raiffa, The Art and Science of Negotiation : How to Resolve Conflicts and Get the Best Out of Bargaining ,Cambridge:Harvard University Press,1982,pp.40-50.

[134] Lance W.Bennet,Regina Lawrence and Steven Livingston, When the Press Fails : From Iraq to Huricane Katnna ,Chicago:University of Chicago Press,2007,p.18.

[135] Douglas Kelner,“Bush Speak and the Politics of Lying:Presidential Rhetoric in the ‘War on Terror’”, Presidential Studies Quarterly ,Vol.37,No.4,2007,pp.622-645.

[136] Christer Jonsson and Karin Aggestam,“Trends in Diplomatic Signalling”,in Jan Melissen ed., Innovation in Diplomatic Practice ,London:Palgrave Macmillan,1999,p.152.

[137] 不少生物学家观察到,动物世界有很多传递信号的例子,那些耗费多余能量长出绚丽羽毛、硕大鹿角或长长尾巴的动物其实就传递出昂贵成本信号。在求偶关系中,信号发送者大多数是雄性,而信号接收者大多数是雌性,那些看起来成本昂贵的信号会在配偶选择中发挥分离性功能,有助于雌雄选择基因强大的配偶。有关进化生物学的信号研究请参见Amos Zahavi,“Mate Selection-A Selection for A Handicap”, Journal of Theoretical Biology ,Vol.53,No.1,1975,pp.205-214;Tim Guilford and Marian Stamp Dawkins,“Receiver Psychology and the Evolution of Animal Signals”, Animal Behaviour ,Vol.42,No.1,1991,pp.1-14;Robert J.Thomas,“The Costs of Singing in Nightingales”, Animal Behaviour ,Vol.63,No.5,2002,pp.959-966。

[138] 参见Robert Jervis, The Logic of Images in International Relations ,Princeton:Princeton University Press,1970;Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics ,Princeton:Princeton University Press,1976。