阿魏作为一种药物/香料/植物,其漫长且循环往复的全球行程始于一种互动,是人类在多种时空背景下,因一定的生物、社会、文化需求,与各种食材之间发生的互动。阿魏不寻常的臭味和它对人体和精神的特殊转化能力被关联起来,使得它在宗教和医学领域具有经久不衰的意义。 [47] 在长安等主要的商业中心,被称为兴渠或阿魏的原料以书面文字的形式出现于烹饪和医学的语境里,也融入在阿拉伯、南亚和东亚不同文化背景下的宇宙观中。它是一种吸引人的香料,甚至是春药,同时也是南亚佛教僧人的禁忌。在整个亚洲文化中,它还是一种被用于驱邪送祟的关键性秘药。尤其在东亚,阿魏重新定义了治疗和医学理论的解释范式,在此其独特的臭味又发挥了关键作用。但臭味也导致它没能在东亚和欧洲成为一种食物。

物质性的变化并没有影响它在南亚市场的受欢迎程度,但在东亚,这导致它从14世纪之后便逐渐衰落了。在抵达东亚之前,通过不受控制的生产过程,一种不被人了解的生料成了流通品。而随着全球市场对它的需求的增加,阿魏作为一种高价商品越来越受到质疑。关于其来源和真实性的信息本就混乱,再加上东亚地区使用这种药物的不同方式,更加剧了这种混乱。在广州、杭州和泉州等中心城市,这类互相矛盾的信息异乎寻常地多。与此同时,药物中那些被认为拥有猛烈效力的成分失去了吸引力,并让步于那些更温和的,常常也是更本土的成分。而且,阿魏那独一无二的恶臭,放大了它那显露于外的生硬粗暴的本性。

当欧洲人对阿魏的兴趣和需求在全球范围内升温的时候,东亚人却开始弃置它,尽管是在完全不同的背景下发生的。16世纪后新的远洋航线开辟,加之想要探寻古老知识,点燃了人们搜寻迪奥斯克里德斯《植物志》( De Materia Medica )中提到的这种原料的强烈愿望。人们将阿魏与被称为松香草的经典食材进行比较,从此揭开各种阿魏属(Ferula)植物之间的差异。对于旅行的外交官、医生、商人、当地贸易商和种植者来说,对于欧洲主要的贸易公司、医学院及其附属植物园中的博物史学家以及19世纪新建立的植物实验室来说,这变成了一个吸引人的项目。直至今天,松香草仍是人们热衷研究的对象(见图6)。随着阿魏种子和植物在全球流通,并且在新的地区适应其生长环境,人们也对所有类型的阿魏进行了化学成分的分析,围绕着“阿魏”这种多面一体的材料,一套全新的知识体系逐渐积累成形。然而,尽管关于它的知识已在全球贸易和学术中心,包括孟买、伦敦、巴黎、日内瓦、爱丁堡、江户和广东等地构成的网络中被重新编纂成文,阿魏的“真实”容貌、阿魏植物以及阿魏树脂的生产制造过程,仍然比以往任何时候都更加捉摸不定。

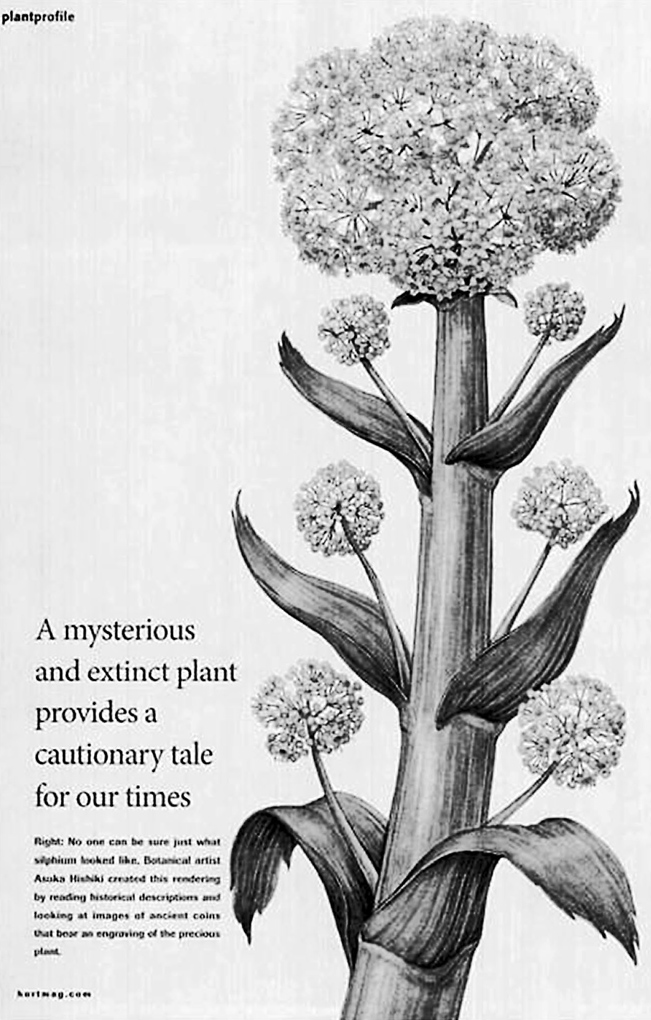

图6 图中呈现了我们今天对松香草的一种现代想象,出自 Horticulture (F&W Media,2010)

(朱霓虹 译,严娜 校)

[1] Angela K. C. Leung and Ming Chen,“The Itinerary of Hing/ Awei /Asafetida across Eurasia,400-1800”,in Entangled Itineraries:Materials,Practices,and Knowledge across Eurasia ,ed. Pamela H. Smith(Pittsburgh:The University of Pittsburgh Press,2019),141-164.

[2] 参见C. Anderson,A. Dunlop,and P. Smith,“Introduction”in their edited volume, The Matter of Art:Materials,Practices Cultural Logics,c . 1250-1750(Manchester:Manchester University Press,2015),2-12;D. Rodgers,“Cultures in Motion:An Introduction,”in Cultures in Motion ,ed. D. Rodgers,B. Raman,and H. Reimitz(Princeton:Princeton University Press,2014),esp.8-12.也可参见研究全球流通商品的先驱之作:Arjun Appadurai ed., The Social Life of Things:Commodities in Cultural Perspectives (Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,1986).

[3] Hobson Jobson, A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases,and of Kindred Terms,Etymological,Historical,Geographical and Discursive (London:J. Murray,1903),418.

[4] A. Dalby, Dangerous Tastes:The Story of Spices (Berkeley:University of California Press,2000),110-112;John H. Balfour, Description of Asafoetida Plants ( Narthex asafetida,Falconer )(Cambridge,MA:Harvard University Herbarium,1860),367.

[5] W. Dymock,C. J. H. Warden,and D. Hooper, Pharmacographia Indica ,vol.2(London:Kegan Paul,1891,Reproduced by Hamdard,The Institute of Health and Tibbi Research,Pakistan,V. XV,1972),148.

[6] B. Laufer,“Three Tokharian Bagatelles,” T'oung Pao 17,no.4/5(1916):273-275.陈明修正了劳佛的观点,提出“awei”是由吐火罗文中的“ankwas(t)”一词转译来的,而这个词与波斯语中的“anguzad”术语密切相关。

[7] 关于吐火罗人的复杂历史和种族渊源,参见Valerie Hansen, The Silk Road:A New History (Oxford:Oxford University Press,2012),70-80,esp.79-80.作者在童丕(Eric Trombert)著作的基础上,证实了当时龟兹贸易商在将龟兹转变成贸易中心的过程中起到的重要作用。

[8] 《十诵律》( Sarvāstivāda-Vinaya. Ten recitations Vinaya ),第二十一卷(CBETA,T23,no.1435,p.157,a1-3);第二十六卷(CBETA,T23 no.1435,p.194,a12-14).

[9] [唐]孙思邈:《千金翼方》,北京:人民卫生出版社,1955年,第232页。有关中国古代疾病传播的观念,参见Angela K. C. Leung,“The evolution of the idea of chuanran contagion,”in Health and Hygiene in Chinese East Asia ,ed. Angela Ki Che Leung and Charlotte Furth(Durham:Duke University Press,2010),31-32;Li Jian-min,“They shall expel demons:etiology,the medical canon and the transformation of medical techniques before the Tang,”in Early Chinese Religion . Part 1: Shang through Han (1250 BC -220 AD ),ed. J. Lagerwey and M. Kalinowski(Leiden:Brill),1103-1150.

[10] Angela K. C. Leung, Leprosy in China:A History (New York:Columbia University Press,2009),54-55.

[11] 慧日和尚的生平,参见[宋]赞宁:《宋高僧传》,第29卷,第890—892页。其他写过或翻译过有关阿魏树脂的佛教僧侣作家有:阿地瞿多(Atigupta),他在公元654年翻译了《陀罗尼集经》( Dhārao ī samuccaya sutra );以及义净(625—713),他撰著了《南海寄归内法传》。

[12] [唐]段成式:《酉阳杂俎》,台北:台湾商务印书馆,1965年,第101页。Diego Santos提出,为段成式提供消息的“拂菻僧弯”,可能是一位默基特(Melkite)天主教徒,他把希腊语、古叙利亚语、阿拉伯语、波斯语的植物知识介绍到中国。参见Diego Santos,“A note on the Syriac and Persian sources of the pharmacological section of the Youyang zazu ,” Collectanea Christiana Orientalia 7(2010):217-229.

[13] 据Robert Hartwell统计,中国港口的国际贸易额度占GNP的1.7%,或者说占10%—20%的非农收入总值,参见Robert Hartwell,“Foreign trade,monetary policy and Chinese mercantilism,”in Collected Studies on Sung History Dedicated to James T. C. Liu in Celebration of his 70 th Birthday ,ed. Kinugawa Tsuyoshi(Kyoto:Sohosha,1989),453-454.

[14] J. Hinrichs and Linda L. Barnes,eds. Chinese Medicine and Healing:An Illustrated History (Cambridge,MA:Harvard University Press,2013),chapter 4.

[15] Lucien Leclerc, Traité des simples (Paris:Institut du monde Arabe,1912),143.

[16] “ T-S Ar . 39.458(Recto)”in Medical Prescriptions in the Cambridge Genizah Collections:Practical Medicine and Pharmacology in medieval Egypt ,ed. E. Lev & L. Chipman(Leiden:Brill,2012),52-54.

[17] Robert Carrubba,“The first report of the harvesting of asafetida in Iran,” Agricultural History 53 no.2(1979):456. 1398年,John Trevisa把1360年的文本从拉丁文译成英语。

[18] 宋岘:《回回药方考释》第1册,北京:中华书局,2000年,前言,第1—31页。同时参见Angela Schottenhammer,“Transfer of Xiangyao from Iran and Arabia to China—A reinvestigation of Entries in the Youyang zaz u(863),”in Aspects of the Maritime Silk Road ,ed. R. Kauz(Wiesbaden:Harrassowitz Verlog,2010),128.

[19] [唐]宇妥·元丹贡布等:《四部医典》,李永年译,北京:人民卫生出版社,1983年,第57页。关于西藏、阿拉伯和印度文化中阿魏作为春药的用法,参见Gyatso and Hakim, Essentials of Tibetan Traditional Medicine (Berkeley:North Atlantic Books,2010),137.

[20] 吕西安·勒克莱尔翻译并注释了伊本·阿尔·贝塔尔在13世纪所著的药典,他注意到“东方人”尤会将阿魏作为调味品使用,然而由于其腥臭的气味,它在欧洲从未作此用途。参见Lucien Leclerc, Traité des simples ,144-145.

[21] 关于蒙古族饮食在中国的影响,参见Thomas Allsen, Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia (Cambridge University Press,2001).尤见第131页关于香料使用的部分。同时参见[元]忽思慧:《饮膳正要》,北京:人民卫生出版社,1986年,第20、21、29、35、251—252页以及它的译注文本P. Buell,E. Anderson,and C. Perry, A Soup for the Qan (Leiden:Brill,2010),106,159,272,287.关于短期存在于中原地区的蒙古族饮食文化的探讨,参见Frederick W. Mote,“Yuan and Ming”,in Food in Chinese Culture ,ed. KC Chang(New Haven:Yale University Press,1977),207-227.

[22] S. R. Whyte,S. Geest,and A. Hardon eds., Social Lives of Medicines (Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,2002),Introduction,esp.7.

[23] Kapil Raj, Relocating Modern Science:Circulation and the Construction of Knowledge in South Asia and Europe ,1650-1900(London:Palgrave Mcmillan,2007),esp. chapter 1.

[24] Garcia da Orta, Seven Colloquy ,in Colóquios dos simples e drogas he cousas medicinais da India ,47.与加西亚·达·奥尔塔同时代的克里斯托旺·德·科斯塔(Cristóvão Da Costa,1515—1594)补充道,树脂在阿拉伯地区和印度被用作春药。德国旅行家约翰·阿尔布雷希特·冯·曼德斯洛(Johann A. Von Mandelslo,1616—1644)曾于17世纪30年代在波斯和印度旅行,他提到印度人食用的“hiṅgu”多数来自波斯,参见Da Costa, Tractado de las drogas,y medicinas de las Indias orientales (Burgos,1578),357. 转引自Berthold Laufer,“Chinese Contributions to the History of Civilization in Ancient Iran,with Special Reference to the History of Cultivated Plants and Products,” Field Museum of Natural History Publication 15,no.3(1967):356.

[25] 有关刚伯法的生平,参见Detlef Haberland,ed., Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716): Ein Gelehrtenleben zwischen Tradition und Innovation (Wiesbaden:Harrassowitz Verlag,2004),尤见第211—225页这一章节:Roelof van Gelder,“Nec semper feriet quodcumque minabitur arcus—Engelbert Kaempfer as a scientist in the service of the Dutch East India Company”.

[26] Robert Carruba,“The first report of the harvesting of asafetida in Iran,” Agricultural History 53 no.2(1979):456.

[27] 刚伯法的简介也见于Robert Carrubba,“The first report of the harvesting of asafetida in Iran,”451-456.刚伯法对阿魏的描述可见于他书中的“第5个观察(observation 5)”,参见其著作 Amoemitatum exoticarum (Limgovine:Tyous & Impensis Henrici Wilhelmi Meyeri Aulae Lippiacae Typographi,1712),535-552.

[28] John Forbes Royle, A Manual of Materia Medica and Therapeutics (London:John Churchill,1876),462-466.

[29] 这些博物学家的记录见于Balfour, Description of Asafoetida Plants ,361-363.

[30] Balfour, Description of Asafoetida Plants ,366-368.

[31] Otsuki Bansui and Otsuki Banri, Ran'en tekihō (Edo:Suharaya Mohe-e,1815).

[32] [明]陈诚:《西域番国志》,北京:中华书局,2000年,第69页。参见Morris Rossabi,“A Translation of Ch'en Ch'eng's Hsi-Y ü Fan-Kuo Chih ,” Ming Studies ,17,no.1(1983):49-59.撒马儿罕在今乌兹别克斯坦南部。

[33] Garcia da Orta, Colloquies ,45-46,48. Carrubba,“First report,”455.

[34] Royle, A Manual ,467.

[35] Leclerc, Traité des simples ,144.

[36] 关于这一显著变化的讨论见Ulrike Unschuld,“Traditional Chinese pharmacology:an analysis of its development in the 13 th century,” ISIS 242,no.68(1977):224-248.

[37] 例如陈嘉谟(1486—1570)的《本草蒙筌》(1565),明万历元年孟秋月,周氏仁寿堂刊,北京大学图书馆藏版,第1卷,第6页。关于中华帝国晚期御用药方书中涉及药物性质讨论的演变过程,参见Bian He,“Assembling the Cure: Materia Medica and the Culture of Healing in Late Imperial China”(PhD diss.,Harvard University,2014),94.

[38] Garcia da Orta, Colloquies ,46-47.

[39] Otsuki Bansui and Otsuki Banri, Ran'en tekihō ,chapter 1,29a-b.

[40] Peter Osbeck, A Voyage to China and the East Indies ,trans. J. Forster,Vol. 1(London:Benjamin White,1771):257.

[41] W. Dymock,C. J. H. Warden,and D. Hooper,147,151;Watt,George, Dictionary of the Economic Products of India ,Vol. 3(Delhi:Periodical Expert,1972 reprint of edition Calcutta,1889-1896),330.

[42] John Fryer, A new Account of East India and Persia:Being Nine Years' Travels ,1672-1681,vol.2(London:Hakluyt Society,1912),195-196.

[43] 最后这个观点是由H. Yule等人在1903年的术语表中提出的,用于指代阿魏的“hing”这一词条下这样写道:“这个产品提供了一个奇特的例子,说明药物的原产地有时会充满不确定性,而原产地正是进行更大宗贸易的目标。”Henry Yule,et al., Hobson-Jobson:A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases,and of Kindred Terms,Etymological,Historical,Geographical and Discursive (London:J. Murray),418.

[44] Balfour, Description of Asafoetida Plants ,361.

[45] 参见Kapil Raj, Relocating Modern Science ,38-59.同样的过程也发生在中国广州,在那里“种植者/采集者和贸易商/博物学家收集有关新植物、新奇物种及其他科学数据,并将这些资料传回英国”,见Fan Fa-ti, British Naturalists in Qing China (Cambridge,MA:Harvard University Press,2004),26.

[46] Nicolas J-B Guibourt, Histoire naturelle des drogues simples. Tome 3 e .(Paris:Chez J.-B. Baillière,1850),223.

[47] 有关医药作为特定的全球流通物品的讨论,参见Whyte,Geest,and Hardon eds., Social Lives of Medicines (Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,2002),esp.5-8.