T HIS IS A BOOK ABOUT bullshit. It is a book about how we are inundated with it, about how we can learn to see through it, and about how we can fight back. First things first, though. We would like to understand what bullshit is, where it comes from, and why so much of it is produced. To answer these questions, it is helpful to look back into deep time at the origins of the phenomenon.

Bullshit is not a modern invention. In one of his Socratic dialogues, Euthydemus, Plato complains that the philosophers known as the Sophists are indifferent to what is actually true and are interested only in winning arguments. In other words, they are bullshit artists. But if we want to trace bullshit back to its origins, we have to look a lot further back than any human civilization. Bullshit has its origins in deception more broadly, and animals have been deceiving one another for hundreds of millions of years.

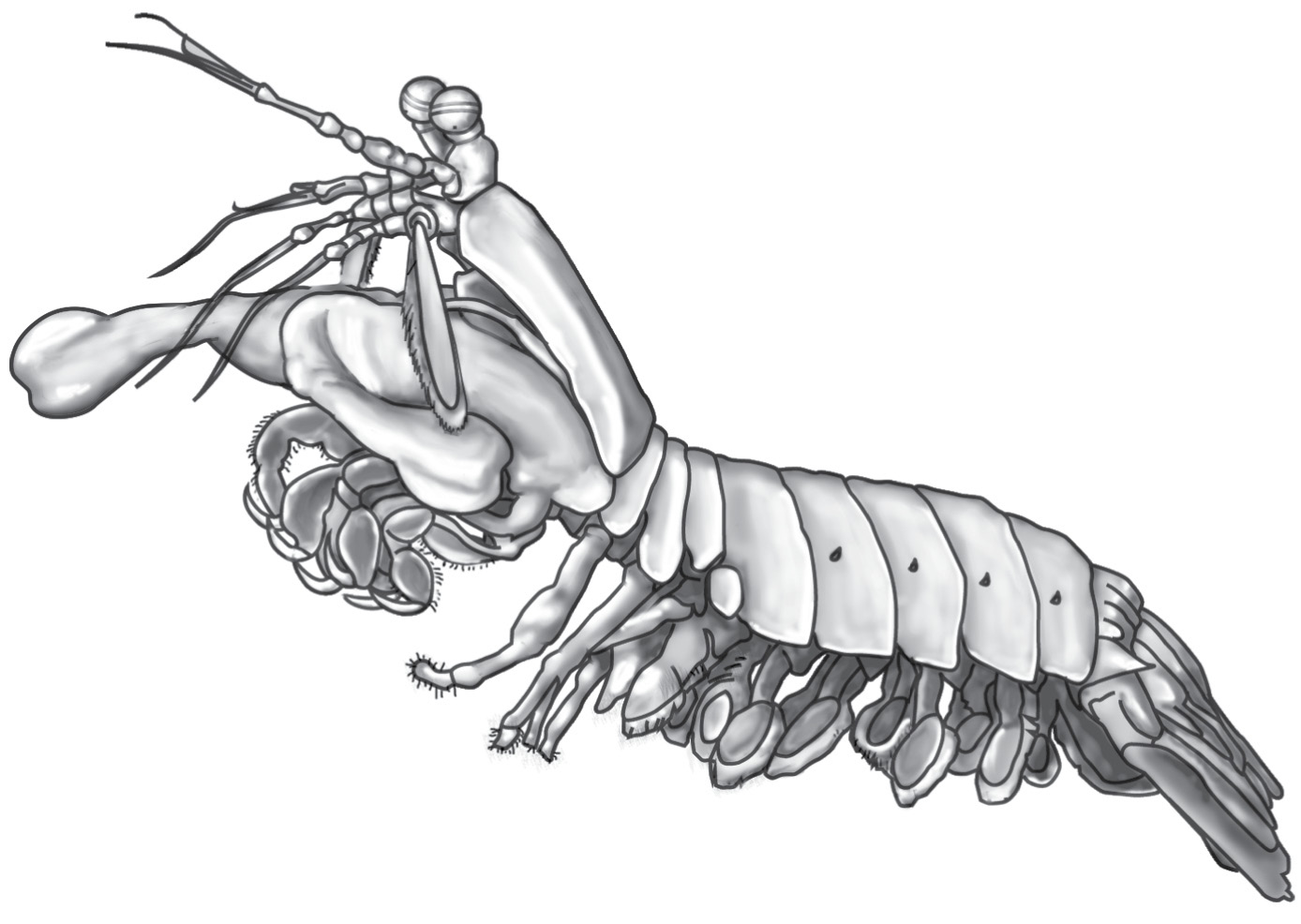

The oceans are full of fierce and wonderful creatures, but few are as badass as the marine crustaceans known as the mantis shrimp or, in more technical circles, stomatopods. Some specialize in eating marine snails, which are protected by hard, thick shells. To smash through these calcite defenses, mantis shrimp have evolved a spring-loading mechanism in their forelimbs that allows them to punch with enormous force. Their hammer-like claws travel 50 mph when they strike. The punch is so powerful that it creates an underwater phenomenon known as cavitation bubbles, a sort of literal Batman “KAPOW!” that results in a loud noise and a flash of light. In captivity they sometimes punch right through the glass walls of their aquariums.

This punching power serves another purpose. Mantis shrimp live on shallow reefs, where they are vulnerable to moray eels, octopi, sharks, and other predators. To stay safe, they spend much of their time holed up in cavities in the reef, with just their powerful foreclaws exposed. But suitable cavities are in short supply, and this can lead to fights. When an intruder approaches a smaller resident, the resident typically flees. But if the resident is big enough, it waves its claws in a fierce display, demonstrating its size and challenging its opponent.

Like any superhero, however, mantis shrimp have an Achilles’ heel. They have to molt in order to replace the hard casings of their hammer claws—which as you can imagine take more than their share of abuse. During the two or three days that the animal is molting, it is extremely vulnerable. It can’t punch, and it lacks the hard shell that normally defends it against predators. Pretty much everything on the reef eats everything else, and mantis shrimp are essentially lobster tails with claws on the front.

So if you’re a molting mantis shrimp holed up in a discreet crevice, the last thing you want to do is flee and expose yourself to the surrounding dangers. This is where the deception comes in. Normally, big mantis shrimp wave their claws—an honest threat—and small mantis shrimp flee. But during molting, mantis shrimp of any size perform the threat display, even though in their current state they can’t punch any harder than an angry gummy bear. The threat is completely empty—but the danger of leaving one’s hole is even greater than the risk of getting into a fight. Intruders, aware that they’re facing the mantis shrimp’s fierce punch, are reluctant to call the bluff.

Stomatopods may be good bluffers, and bluffing does feel rather like a kind of bullshit—but it’s not very sophisticated bullshit. For one thing, this behavior isn’t something that these creatures think up and decide to carry out. It is merely an evolved response, a sort of instinct or reflex.

A sophisticated bullshitter needs a theory of mind —she needs to be able to put herself in the place of her mark. She needs to be able to think about what the others around her do and do not know. She needs to be able to imagine what impression will be created by what sort of bullshit, and to choose her bullshit accordingly.

Such advanced cognition is rare in the animal kingdom. We have it. Our closest primate relatives, chimpanzees and gorillas, may have it as well. Other apes and monkeys do not seem to have this capacity. But one very different family does: Corvidae.

We know that corvids—ravens, crows, and jays—are remarkably intelligent birds. They manufacture the most sophisticated tools of any nonhuman species. They manipulate objects in their environment to solve all manners of puzzle. The Aesop’s fable about the crow putting pebbles into an urn to raise the water level is probably based on a real observation; captive crows can figure out how to do this sort of thing. Ravens plan ahead for the future, selecting objects that may be useful to them later. Crows recognize human faces and hold grudges against those who have threatened or mistreated them. They even pass these grudges along to their fellow crows.

We don’t know exactly why corvids are so smart, but their lifestyle does reward intelligence. They live a long time, they are highly social, and they creatively explore their surroundings for anything that might be edible. Ravens in particular may have evolved alongside pack-hunting species such as wolves and ourselves, and are excellent at tricking mammals out of their food.

Because food is sometimes plentiful and other times scarce, most corvid species cache their food, storing it in a safe place where it can be recovered later. But caching is a losing proposition if others are watching. If one bird sees another cache a piece of food, the observer often steals it. As a result, corvids are cautious about caching their food in view of other birds. When being watched, ravens cache quickly, or move out of sight before hiding their food. They also “fake-cache,” pretending to stash a food item but actually keeping it safely in their beak or crop to be properly cached at a later time.

So when a raven pretends to cache a snack but is actually just faking, does that qualify as bullshitting? In our view, this depends on why the raven is faking and whether it thinks about the impression its fakery will create in the mind of an onlooker. Full-on bullshit is intended to distract, confuse, or mislead—which means that the bullshitter needs to have a mental model of the effect that his actions have on an observer’s mind. Do corvids have a theory of mind? Do they understand that other birds can see them caching and are likely to steal from them? Or do they merely follow some simple rule of thumb—such as “cache only when no other ravens are around”—without knowing why they are doing so? Researchers who study animal behavior have been hard-pressed to demonstrate that any nonhuman animals have a theory of mind. But recent studies suggest that ravens may be an exception. When caching treats, they do think about what other ravens know. And not only do ravens act to deceive other birds sitting right there in front of them; they recognize that there might be other birds out there, unseen, who can be deceived as well. *1 That is pretty close to what we do when we bullshit on the Internet. We don’t see anyone out there, but we hope and expect that our words will reach an audience.

Ravens are tricky creatures, but we humans take bullshit to the next level. Like ravens, we have a theory of mind. We can think in advance about how others will interpret our actions, and we use this skill to our advantage. Unlike ravens, we also have a rich system of language to deploy. Human language is immensely expressive, in the sense that we can combine words in a vast number of ways to convey different ideas. Together, language and theory of mind allow us to convey a broad range of messages and to model in our own minds what effects our messages will have on those who hear them. This is a good skill to have when trying to communicate efficiently—and it’s equally useful when using communication to manipulate another person’s beliefs or actions.

That’s the thing about communication. It’s a two-edged sword. By communicating we can work together in remarkable ways. But by paying attention to communication, you are giving other people a “handle” they can use to manipulate your behavior. Animals with limited communication systems—a few different alarm calls, say—have just a few handles with which they can be manipulated. Capuchin monkeys warn one another with alarm calls. On average this saves a lot of capuchin lives. But it also allows lower-ranking monkeys to scare dominant individuals away from precious food: All they have to do is send a deceptive alarm call in the absence of danger. Still, there aren’t all that many things capuchins can say, so there aren’t all that many ways they can deceive one another. A capuchin monkey can tell me to flee, even if doing so is not in my best interest. But it can’t, say, convince me that it totally has a girlfriend in Canada; I’ve just never met her. Never mind getting me to transfer $10,000 into a bank account belonging to the widow of a mining tycoon, who just happened to ask out of the blue for my help laundering her fortune into US currency.

So why is there bullshit everywhere? Part of the answer is that everyone, crustacean or raven or fellow human being, is trying to sell you something. Another part is that humans possess the cognitive tools to figure out what kinds of bullshit will be effective. A third part is that our complex language allows us to produce an infinite variety of bullshit.

We impose strong social sanctions on liars. If you get caught in a serious lie, you may lose a friend. You may get punched in the nose. You may get sued in a court of law. Perhaps worst of all, your duplicity may become the subject of gossip among your friends and acquaintances. You may find yourself no longer a trusted partner in friendship, love, or business.

With all of these potential penalties, it’s often better to mislead without lying outright. This is called paltering . If I deliberately lead you to draw the wrong conclusions by saying things that are technically not untrue, I am paltering. Perhaps the classic example in recent history is Bill Clinton’s famous claim to Jim Lehrer on Newshour that “there is no sexual relationship [with Monica Lewinsky].” When further details came to light, Clinton’s defense was that his statement was true: He used the present-tense verb “is,” indicating no ongoing relationship. Sure, there had been one, but his original statement hadn’t addressed that issue one way or the other.

Paltering offers a level of plausible deniability—or at least deniability. Getting caught paltering can hurt your reputation, but most people consider it less severe an offense than outright lying. Usually when we get caught paltering, we are not forced to say anything as absurdly lawyerly as Bill Clinton’s “It depends upon what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is.”

Paltering is possible because of the way that we use language. A large fraction of the time, what people are literally saying is not what they intend to communicate. Suppose you ask me what I thought of David Lynch’s twenty-fifth-anniversary Twin Peaks reboot, and I say, “It wasn’t terrible.” You would naturally interpret that to mean “It wasn’t very good either”—even though I haven’t said that. Or suppose when talking about a colleague’s recreational habits I say, “John doesn’t shoot up when he is working.” Interpreted literally, this means only that John doesn’t do heroin when he is working and gives you no reason to suspect that John uses the drug after hours either. But what this sentence implies is very different. It implies that John is a heroin user with a modicum of restraint.

Within linguistics, this notion of implied meaning falls under the area of pragmatics . Philosopher of language H. P. Grice coined the term implicature to describe what a sentence is being used to mean, rather than what it means literally. Implicature allows us to communicate efficiently. If you ask where you can get a cup of coffee and I say, “There’s a diner just down the block,” you interpret my response as an answer to your question. You assume that the diner is open, that it serves coffee, and so forth. I don’t have to say all of that explicitly.

But implicature is also what lets us palter. The implicature of the claim “John doesn’t shoot up when working” is that he does shoot up at other times. Otherwise, why wouldn’t I have just said that John doesn’t shoot drugs, period?

Implicature provides a huge amount of wiggle room for people to say misleading things and then claim innocence afterward. Imagine that John tried to take me to court for slandering him by my saying he doesn’t shoot up at work. How could he possibly win? My sentence is true, and he has no interest in claiming otherwise. People all too often use this gulf between literal meaning and implicature to bullshit. “He’s not the most responsible father I’ve ever known,” I say. It’s true, because I know one dad who is even better—but you think I mean that he’s a terrible father. “He will pay his debts if you prod him enough.” It’s true, because he’s an upright guy who quickly pays his debts without prompting, but you think I mean that he’s a cheapskate. “I got a college scholarship and played football.” It’s true, though my scholarship was from the National Merit society and I played touch football with my buddies on Sunday mornings. Yet you think I was a star college athlete.

An important genre of bullshit known as weasel wording uses the gap between literal meaning and implicature to avoid taking responsibility for things. This seems to be an important skill in many professional domains. Advertisers use weasel words to suggest benefits without having to deliver on their promises. If you claim your toothpaste reduces plaque “by up to” 50 percent, the only way that would be false is if the toothpaste worked too well. A politician can avoid slander litigation if he hedges: “People are saying” that his opponent has ties to organized crime. With the classic “mistakes were made,” a manager goes through the motions of apology without holding anyone culpable.

Homer Simpson understood. Defending his son, Bart, he famously implored “Marge, don’t discourage the boy. Weaseling out of things is important to learn. It’s what separates us from the animals….Except the weasel.”

Homer’s joking aside, corporate weaselspeak diffuses responsibility behind a smoke screen of euphemism and passive voice. A 2019 NBC News report revealed that many global manufacturers were likely using materials produced by child labor in Madagascar. A spokesperson for Fiat Chrysler had this to say: Their company “engages in collaborative action with global stakeholders across industries and along the value chain to promote and develop our raw material supply chain.” Collaborative action? Global stakeholders? Value chain? We are talking about four-year-olds processing mica extracted from crude mines. Entire families are working in the blazing sun and sleeping outside all night for forty cents a day. This is bullshit that hides a horrible human toll behind the verbiage of corporate lingo.

Some bullshitters actively seek to deceive, to lead the listener away from truth. Other bullshitters are essentially indifferent to the truth. To explain, let’s return from weasels back to the animal-signaling stories with which we began this chapter. When animals communicate, they typically send self-regarding signals . Self-regarding signals refer to the signaler itself rather than to something in the external world. For example, “I’m hungry,” “I’m angry,” “I’m sexy,” “I’m poisonous,” and “I’m a member of the group” are all self-regarding signals because they convey something about the signaler.

Other-regarding signals refer to elements of the world beyond the signaler itself. Such signals are uncommon among animal signals, with the notable exception of alarm calls. Most nonhuman animals simply don’t have ways to refer to external objects. Humans are different. One of the novel or nearly novel features of human language is that human language gives us the vocabulary and grammar to talk about not only ourselves but also other people and other external objects in the world.

But even when humans are ostensibly communicating about elements of the external world, they may be saying more about themselves than it seems. Think about meeting someone for the first time at a party or other social event and falling into conversation. Why do you tell the stories that you do? Why do you talk at all, for that matter? Your stories don’t just inform the other person about aspects of the world. They convey things about who you are—or at least about whom you want to be. Maybe you’re trying to come off as brave and adventurous. Or maybe sensitive and troubled. Maybe you’re iconoclastic. Maybe you’re a master of self-deprecating humor. We tell stories to create impressions of ourselves in the eyes of others.

This impulse drives a lot of bullshit production. When you’re talking about a crazy adventure you had on a backpacking trip through Asia, your story doesn’t actually need to be true to create the impression you are seeking. You often don’t care one way or the other. Your story just needs to be interesting, impressive, or engaging. One need only to sit around with friends and a shared pitcher of beer to see this firsthand. This kind of bullshit has become an art form in the so-called attention economy. Think about the stories that go viral on social media: funny things that kids say, horrible first dates, trouble that pets get into. These may or may not be true, and to most people who read them, it doesn’t matter.

Just because people can spew bullshit doesn’t mean that they will, nor does it mean that bullshit will not be quickly eradicated by the force of truth. So why is bullshit ubiquitous?

Perhaps the most important principle in bullshit studies is Brandolini’s principle. Coined by Italian software engineer Alberto Brandolini in 2014, it states:

“The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than [that needed] to produce it.”

Producing bullshit is a lot less work than cleaning it up. It is also a lot simpler and cheaper to do. A few years before Brandolini formulated his principle, Italian blogger Uriel Fanelli had already noted that, loosely translated, “an idiot can create more bullshit than you could ever hope to refute.” Conspiracy theorist and radio personality Alex Jones need not be an evil genius to spread venomous nonsense such as his Sandy Hook denialism and Pizzagate stories; he could be an evil idiot—or even a misguided one.

Within the field of medicine, Brandolini’s principle is exemplified by the pernicious falsehood that vaccines cause autism. After more than twenty years of research, there is no evidence that vaccines cause autism; indeed there is overwhelming evidence that they do not. Yet misinformation about vaccines persists, due in large part to a shockingly poor 1998 study published in The Lancet by British physician Andrew Wakefield and colleagues. In that article, and in numerous subsequent press conferences, Wakefield’s research team raised the possibility that a syndrome involving autism paired with inflammatory bowel disease may be associated with the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine. *2

Wakefield’s paper galvanized the contemporary “antivax” movement, created a remarkably enduring fear of vaccines, and contributed to the resurgence of measles around the world. Yet seldom in the history of science has a study been so thoroughly discredited. Millions of dollars and countless research hours have been devoted to checking and rechecking this study. It has been utterly and incontrovertibly discredited. *3

As the evidence against the MMR-autism hypothesis piled up and as Wakefield’s conflicts of interest came to light, most of Wakefield’s co-authors started to lose faith in their study. In 2004, ten of them formally retracted the “interpretations” section of the 1998 paper. Wakefield did not sign on to the retraction. In 2010, the paper was fully retracted by The Lancet .

The same year, Wakefield was found guilty of serious professional misconduct by Britain’s General Medical Council. He was admonished for his transgressions surrounding the 1998 paper, for subjecting his patients to unnecessary and invasive medical procedures including colonoscopy and lumbar puncture, and for failure to disclose financial conflicts of interest. *4 As a result of this hearing, Wakefield’s license to practice medicine in the UK was revoked. In 2011, British Medical Journal editor in chief Fiona Godlee formally declared the original study to be a fraud, and argued that there must have been intent to deceive; mere incompetence could not explain the numerous issues surrounding the paper.

These ethical transgressions are not the strongest evidence against Wakefield’s claim of an autism-vaccine link. Wakefield’s evidence may have been insufficient to justify his conclusions. His handling of the data may have been sloppy or worse. His failure to follow the ethics of his profession may have been egregious. The whole research paper may have indeed been an “elaborate fraud” rife with conflicts of interest and fabricated findings. In principle Wakefield’s claim could still have been correct. But he is not correct. We know this because of the careful scientific studies carried out on a massive scale. It is not the weaknesses in Wakefield’s paper that prove there is no autism-vaccine link: it is the overwhelming weight of subsequent scientific evidence .

To be clear, there was nothing inappropriate about looking to see if there is a connection between autism and vaccination. The problem is that the original study was done irresponsibly at best—and that when its frightening conclusions were definitively disproven, antivaxxers invented a story about a Big Pharma conspiracy to hide the truth. Wakefield eventually directed a documentary titled Vaxxed, which alleged that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was covering up safety problems surrounding vaccines. The film received a large amount of press attention and reinvigorated the vaccine scare. Despite all the findings against Wakefield and the crushing avalanche of evidence against his hypothesis, Wakefield retains credibility with a segment of the public and unfounded fears about a vaccine-autism link persist.

TWO DECADES LATER, WAKEFIELD’S hoax has had disastrous public health consequences. Vaccine rates have risen from their nadir shortly after Wakefield’s paper was published, but remain dangerously lower than they were in the early 1990s. In the first six months of 2018, Europe reported a record high 41,000 measles cases. The US, which had nearly eliminated measles entirely, now suffers large outbreaks on an annual basis. Other diseases such as mumps and whooping cough (pertussis) are making a comeback. Particularly in affluent coastal cities, many Americans are skeptical that vaccines are safe. One recent trend is for parents to experiment with delayed vaccination schedules. This strategy has no scientific support and leaves children susceptible for a prolonged period to the ravages of childhood diseases. Children with compromised immune systems are particularly vulnerable. Many of them cannot be vaccinated, and rely for their safety on the “herd immunity” that arises when those around them are vaccinated.

So here we have a hypothesis that has been as thoroughly discredited as anything in the scientific literature. It causes serious harm to public health. And yet it will not go away. Why has it been so hard to debunk the rumors of a connection between vaccines and autism? This is Brandolini’s principle at work. Researchers have to invest vastly more time to debunk Wakefield’s arguments than he did to produce them in the first place.

This particular misconception has a number of characteristics that make it more persistent than many false beliefs. Autism is terrifying to parents, and as yet we do not know what causes it. Like the most successful urban legends, the basic narrative is simple and gripping: “A child’s vulnerable body is pierced with a needle and injected with a foreign substance. The child seems perfectly fine for a few days or even weeks, and then suddenly undergoes severe and often irreversible behavioral regression.” This story taps into some of our deepest fears—in this case, fears about hygiene and contamination, and anxiety about the health and safety of our children. The story caters to our desire for explanations, and to our tendency to ascribe cause when we see two events occurring in succession. And it hints at a way we might protect ourselves. Successfully refuting something like this is a decidedly uphill battle.

Bullshit is not only easy to create, it’s easy to spread. Satirist Jonathan Swift wrote in 1710 that “falsehood flies, and truth comes limping after it.” *5 This saying has many different incarnations, but our favorite is from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s secretary of state, Cordell Hull: “A lie will gallop halfway round the world before the truth has time to pull its breeches on.” We envision hapless Truth half-running and half-tripping down the hallway, struggling to pull its pants up from around its ankles, in hopeless pursuit of a long-departed Lie.

Taken together, Brandolini’s principle, Fanelli’s principle, and Swift’s observation tell us that (1) bullshit takes less work to create than to clean up, (2) takes less intelligence to create than to clean up, and (3) spreads faster than efforts to clean it up. Of course, they are just aphorisms. They sound good, and they feel “truthy,” but they could be just more bullshit. In order to measure bullshit’s spread, we need an environment where bullshit is captured, stored, and packaged for large-scale analysis. Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms provide such environments. Many of the messages sent on these platforms are rumors being passed from one person to the next. Rumors are not exactly the same as bullshit, but both can be products of intentional deception.

Retracing the path of a rumor’s spread is largely a matter of looking at who shared what with whom and in what order, all information that is readily available given adequate access to the system. Tweets about crises are particularly consequential. The concentration of attention during these events creates both the incentive to generate misinformation, and a vital need to refute it.

One such crisis was the terrorist bombing of the Boston Marathon in 2013. Shortly after the attack, a tragic story appeared on Twitter. An eight-year-old girl was reported to have been killed in the bombing. This young girl had been a student at Sandy Hook Elementary School, and she was running the marathon in memory of her classmates who were killed in the horrific mass shooting that had occurred there a few months prior. The terrible irony of her fate, surviving Sandy Hook only to die in the Boston Marathon bombing, propelled her story to spread like wildfire across the Twitter universe. The girl’s picture—bib #1035 over a fluorescent pink shirt, ponytail streaming behind her—led thousands of readers to respond with grief and compassion.

But other readers questioned the story. Some noted that the Boston Marathon does not allow kids to run the race. Others noticed that her bib referred to a different race, the Joe Cassella 5K. Rumor-tracking website Snopes.com quickly debunked the rumor, as did other fact-checking organizations. The girl hadn’t been killed; she hadn’t even run the race. Twitter users tried to correct the record, with more than two thousand tweets refuting the rumor. But these were vain efforts. More than ninety-two thousand people shared the false story of the girl. Major news agencies covered the story. The rumor continued to propagate despite the many attempts to correct it. Brandolini was right yet again.

Researchers at Facebook have observed similar phenomena on their platform. Tracing rumors investigated by Snopes, the researchers found that false rumors spread further than true rumors, even after the claim had been debunked by Snopes. Posts that spread false rumors are more likely to be deleted after being “Snoped,” but they are seldom taken down quickly enough to stop the propagation of false information.

Other researchers have looked at what drives these rumor cascades. When comparing conspiracy theory posts to posts on other subjects, conspiracy theories have much larger reach. This makes it especially difficult to correct a false claim. Jonathan Swift’s intuition about bullshit has been well corroborated. People who clean up bullshit are at a substantial disadvantage to those who spread it.

Truth tellers face another disadvantage: The ways that we acquire and share information are changing rapidly. In seventy-five years we’ve gone from newspapers to news feeds, from Face the Nation to Facebook, from fireside chats to firing off tweets at four in the morning. These changes provide fertilizer for the rapid proliferation of distractions, misinformation, bullshit, and fake news. In the next chapter, we look at how and why this happened.

*1 One experiment worked as follows. A first raven was given food to cache, while a second raven in an adjacent room watched through a large window. Knowing that it was being watched, the raven with the food would cache hastily and avoid revisiting the cache lest it give away the location. If the investigators placed a wooden screen over the window so that the ravens could not see each other, the raven with the food took its time to cache its food and unconcernedly revisited the cache to adjust it.

Then the investigators added a small peephole to the screen covering the window, and gave the ravens time to learn that they could see each other by peering into the peephole. Then they removed the watching raven from the cage, so that no one was watching through the peephole. The key question was, what will a raven do when the peephole is open, but it cannot directly see whether or not there is a bird watching from within the cage? If the ravens use a simple rule of thumb like “when you can see the other bird, behave as though you are being watched,” they should ignore the peephole. If ravens have a theory of mind, they would realize that they might be under observation through the peephole even if they don’t see another bird, and would behave as if they were being watched. This is exactly what the ravens did. The researchers concluded that the ravens were generalizing from their own experience of watching through the peephole, and recognized that when the peephole was open, an unseen bird could be watching them.

*2 One of the immediately apparent problems with Wakefield’s study was the tiny sample size. His study looked at only twelve children, most of whom reportedly developed the purported syndrome shortly after receiving the MMR vaccine. It is very difficult, if not impossible, to draw meaningful conclusions about rare phenomena from such a tiny sample.

Yet the small sample size of his study was the least of his problems. A subsequent investigation revealed that for many of the twelve patients, the Lancet paper described ailments and case histories that did not match medical records or reports from the parents. In a scathing article for the British Medical Journal, journalist Brian Deer enumerated a host of issues, including: Three of twelve patients listed as suffering from regressive autism did not have autism at all; in several cases the timing of onset of symptoms was not accurately reported; and five of the children reported as normal prior to the vaccine had case histories reflecting prior developmental issues.

*3 Wakefield’s claims came under scrutiny almost immediately after his paper was published. Within a year of Wakefield’s publication, The Lancet published another study investigating a possible vaccination-autism link. This study used careful statistical analysis on a much larger sample—498 autistic children—and found no association whatsoever.

This was only the beginning. On the mechanistic side, other researchers were unable to replicate the original claims that the measles virus persists in the gut of Crohn’s disease patients. On the epidemiological side, numerous studies were conducted and found no association between the vaccine and autism. For example, in 2002, Pediatrics published a study of over half a million Finnish children, and The New England Journal of Medicine published a study of over half a million Danish children. Neither found any connection, and the conclusion of the Danish study states bluntly, “This study provides strong evidence against the hypothesis that MMR vaccination causes autism.”

A natural experiment took place in Japan when the MMR vaccine was replaced by monovalent (single-disease) vaccines in 1993. If Wakefield’s hypothesis—that the combined MMR vaccine can cause autism whereas giving three vaccines, one for each disease, should be safe—we would have seen a decrease in autism rates in Japan. That did not happen. More recently, a meta-analysis combining data from multiple studies looked at 1.3 million children and again found no relation between vaccination and autism.

*4 Investigative work by journalist Brian Deer revealed that Wakefield was concealing massive conflicts of interest. At the time he was working on the 1998 paper, Wakefield’s research was being funded by a lawyer who was putting together a lawsuit against a vaccine manufacturer. Wakefield’s purported vaccine-autism link was to be a major feature of the lawsuit. Over the course of a decade, Wakefield ultimately received well over £400,000 from the UK Legal Services Commission for his work on this lawsuit. Professional ethics require that an author disclose any financial interest he or she has in a published paper, but Wakefield did not do so in his Lancet report. Moreover, his co-authors were reportedly unaware that he was being paid for this work. There was another financial conflict of interest. Prior to publishing his paper Wakefield had filed at least two patent applications, one for a diagnostic test for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis by the presence of the measles virus in the bowel, and a second one for the production of a “safer” measles vaccine. The commercial value of each hinged upon proving his theory that the MMR vaccine was associated with autism and inflammatory bowel disorders. According to Deer, Wakefield also helped to launch, and held a substantial equity stake in, startup companies in this domain.

*5 The full quotation is: “Falsehood flies, and truth comes limping after it, so that when men come to be undeceived, it is too late; the jest is over, and the tale hath had its effect: like a man, who hath thought of a good repartee when the discourse is changed, or the company parted; or like a physician, who hath found out an infallible medicine, after the patient is dead.”