The roots of Ayurvedic science are so ancient that it is difficult to conjure up the chronological history of Ayurveda. Long before Ayurveda was documented in writing, it existed as an oral tradition. The preceptor and the pupil recited hymns that conveyed Ayurvedic knowledge; this tradition exists even today in certain traditional families, where the knowledge is passed from one generation to the next by reciting the hymns and memorizing them. One can clearly observe that Ayurveda has been a living tradition for quite a long time and that its concepts remain intertwined with present-day life on the Indian subcontinent.

The number of Ayurvedic literary works available shows that Ayurveda had a glorious past. Albrecht Weber in his History of Indian Literature remarks:“The number of medical works (compiled in Sanskrit language) and authors is extraordinarily large. The sum of knowledge embodied in their content appears really to be the most respectable. Many of the statements on dietetics and on origin and diagnosis of disease they speak a very keen observation. Also, in surgery, the Indians seem to have attained a special prophecy and proficiency. European surgeons might perhaps still learn something from them as indeed they have already borrowed from them, the operation of rhinoplasty.” In one of the most ancient medical works of Ayurveda, the Charaka Samhita , its author, Charaka, states “Ayurveda(knowledge of life) is eternal”. The explanation for the eternal nature of Ayurveda is linked to the mystery of the origins of human life. Since the origins of human life cannot be determined,so is the knowledge of life. Charaka holds Ayurveda higher than any other knowledge as it imparts health without which human life cannot progress. The information in the history sections were compiled from the History of Indian Medicine by Mukhopadhyaya, History of Ayurveda by N.K. Krishna Kutty Warrier,and Handbook of History of Ayurveda by Dr. K.Nishteswar. [1–3]

In order to understand the origins and historic development of Ayurveda we have to comb through the literature in chronological order, starting from the following five sources:The Vedas, Upanishadic literature, Purana literature, Buddhist literature and Medival period.

In his classical compilation of surgical procedures, the Sushruta Samhita , Sushruta,the Father of Surgery, described Ayurveda as an upaveda (sub-branch) of the Atharva Veda.The Atharva Veda is the last among the four canons of Vedic literature. To know the origins of Ayurveda it is important to explore the four Vedas, namely Rig Veda, Yajur Veda, Sama Veda, Atharva Veda.

Unquestionably the Vedas are one of the most ancient literatures available to humans.Literally word veda in Sanskrit language originates from the root vid , which means“to know or to reason upon”. The purpose of Vedas is to elevate human values and raise human consciousness. The Vedic civilization documented in the Vedas can be approximately placed in the late Mesolithic age, which archaeologically and historically refers to the period between 5000 BCE to 3500 BCE, when early humans started settling down in farming villages. The dates when these villages emerged vary widely across different geographical regions. Geographically, excavations at Indus Valley sites link the early Vedic period to Indus Valley civilization, and archeologically, the sites and numerous artifacts discovered there directly correlate with references found in the Rig Veda. In contrast, references in the last of the four Vedas, namely, the Atharva Veda,link Vedic civilization to the Gangetic Valley.This evidence suggests that Vedic civilization spanned for over 2,000 years, starting with early human settlements in the Indus Valley and continuing to evolve into an advanced society in the Gangetic Valley. The excavations of Neolithic archaeological sites in south central Asia, including the pre-Harappa phase in the Baluchistan region, also point to a connection between the Indus Valley sites and Vedas.Additionally, excavations in and historical references to the Gangetic Valley of the Indian subcontinent show a continuum of traditions across this period.

A detailed study of food articles and herbs used in the Vedic ceremonies, as well as healing practices recorded in the Vedas, suggests that Ayurveda co-evolved and co-existed with the earlier volumes of the Vedas and is entitled to equal respect. Its association with the Atharva Veda seems to stem mainly from the fact that both of them deal with methods of disease management and detail practices that promote long life. Information about medicine and healing practices appears frequently throughout the Vedas and is included in the literature as far back its first volume, the Rig Veda. A comparison of the four Vedas indicates that the amount of information pertaining to healing gradually increased over the period extending from the appearance of Rig Veda to the later arrival of the Atharva Veda. Traditionally attributed to a class of holy sages known as Atharvans, the Atharva Veda describes various treatment modalities, elaborating in detail on the origins and pathogenesis of a variety of diseases and enumerating remedies. Ayurveda seems to have branched out from Atharva Veda due to its extensive information about health and disease management. The celebrated commentator on the Charaka Samhita , Chakrapani Datta(12 th century CE) noted that the Atharva Veda itself evolved into Ayurveda as the information contained in it primarily focused on therapeutics.Scholar Darila-Bhatta, an early commentator on the Atharva Veda’s Kaushika Sutra section explained the difference between Ayurveda and Atharva Veda in terms of their contrasting goals.He noted that there are two kinds of diseases:those that stem from an unwholesome diet and those result from sins and transgressions.Ayurveda aims to increase knowledge of diseases of the first type, whereas Atharva Veda focuses on with second kind.

The origins of many Ayurvedic theories trace back to the earliest Vedas. One such doctrine is the connection between the “macrouniverse” and “micro-human body”. This analogy between nature and the human body appears in the Rig Veda’s observations on the similarities between the body and rest of the material universe in terms of their makeup,operation, and constituent elements. Ayurveda’s focus on the role of balance in health and disease likewise appears rooted in the Rig Veda. The Rig Veda’s conception of the wind,sun, and water as forces that can manifest as either supportive or destructive is echoed in the Atharva Veda’s view of health or disease as an outcome determined by the balance or the imbalance of these forces. Sayana, the famous commentator on the Vedas, interprets these three elemental forces as precursors of the three doshas (vata, pitta and kapha). The tridosha(three humoral) doctrine of Ayurveda also reflects this Vedic concept.

The Rig Veda identified a number of anatomical structures that roughly correspond to those defined in modern anatomy. The following list shows the correlation between the structures described in the Vedas and their modern equivalents: Hridaya (heart), Yakrit (liver), Pleeha (spleen), Antra (intestines), Kaphodau (lungs), Kukshi (stomach), Kloma (pancreas), Mastishka (brain), Vasti (bladder), Gaveni (ureters), Vrishana (testes), Guda (anus), Manya (neck), Dhamani (arteries), and Nadi (nerves).

The Atharva Veda also details many features of human anatomy. In its discussion on the creation of human body and various structures that constitute it, this text names several different skeletal structures, including the following: Gulpha (comparable to heel), Anguli (identified as digits), Shroni (comparable to pelvic cavity), Uru (identified as femur), Uras (comparable to thoracic cavity), Greeva (comparable to cervical region), Skandha (identified as trunk), Prishta (comparable to spine), Amsa (identified as contour of the shoulder), Lalata (identified as forehead), Kapala (comparable to cranial vault),and Hanu (identified as jaw).

Physiological processes such as circulation,metabolism, and immune function are also explained in Vedic literature. The location,structure, and physiology of the heart, as well as the circulation of blood are precisely described.

The Sama Veda presents its explanation of the digestion, absorption, and assimilation of food in the form of a dialogue between Swetaketu and his father Uddalaka. The father’s description of this process prefigures the Ayurvedic concept of agni (digestive fire) as a primal transformative force: “While the universal consciousness itself is without a cause and uncreated, it is the cause and creator of all. Standing alone, it wanted to be many and became many by taking the form of fire. The highest being of all exists as Agni (fire), whose essence is heat and light.As a conveyor of all things it exists in us as the digestive fire and consumes the food we eat through the heat it generates.”

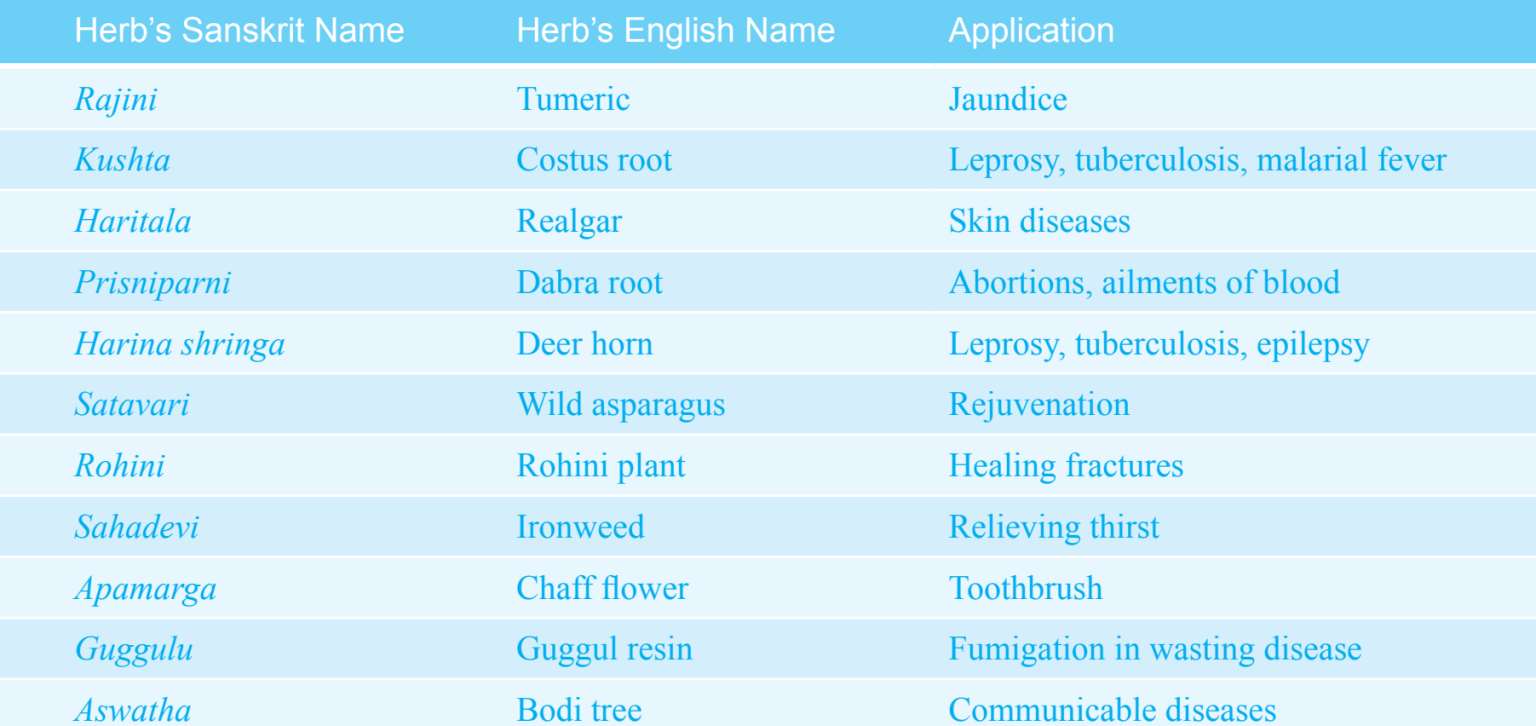

Discussions of herbal, mineral, and animal products used in the various rituals and healing practices appear in all four Vedas. Medicinal plants are classified based on the morphology and their properties and special actions (Table 1–1). Some of the herbs are said to have powerful healing effects, such as the removal of deepseated pathological imbalances. These herbs were used externally as well as internally to ward off the negative consequences of diseases attributed to nonrighteous actions and sins.In addition to numerous medicinal herbs, the Vedas describe a wide range of minerals, such as iron, gold, silver, that were used for health purposes.

Table 1–1 Medicinal Herbs Described in the Vedas

In Vedic tradition, the word soma is associated plants whose juice was said to confer immortality. Ritual offerings of this juice in Vedic fire ceremonies was believed to enhance the well-being of all the members of the family and the community. Considered the king of plants,soma is frequently cited in ancient Ayurvedic texts as an elixir of long life and rejuvenation.

Internal administration of a single herb was a prevalent healing practice during this period. The herbs administered in these healing rituals, which often involved the use of gems and chanting, were said to have potent physical and spiritual properties. Divine therapeutic measures were indispensible to any type of healing ritual or disease treatment.

Properties of medicinal herbs recorded in the Vedas:

A shrub known as ajashringi that emits intensive odor like that of an antelope was said to repel rakshasas (evil spirits).

Apamarga was used an anti-parasitic and antidote for poisons. The same plant is said to help with dysuria.

The ashwatha tree was highly revered for its spiritual power. Its twigs served as offerings in fire ceremonies to help bring wellness to the community and to ward off infectious diseases.

The substitution of arjuna (also known as phalguna ) for the soma plant when it was not available demonstrates the acceptance of substitution of substances during the Vedic period.

Chitraparni (a plant with variegated leaves) was said to protect and nourish the fetus. The variegated leaves were also thought to be helpful in removing skin discolorations. This idea reflects the “doctrine of signatures”, the belief that characteristics of a plant, such as its appearance or smell, reveal the condition of the body that it can heal.

Guggulu was burned as incense during healing rituals. Inhaling the fumes was believed to be therapeutic.

Numerous references to the use of medicinal plants for veterinary purposes are also found in the Vedas.

The following list shows the Sanskrit names of diseases mentioned in Vedas. The English definition for each one describes the condition it is believed to be comparable to: Jwara [ takma (fever)], Kasa (cough), Balasa (emaciating disease), Apachi (soft tissue swelling), Jayanya (wasting disease), Harima (jaundice), Mutrarodha (urinary obstruction), Kilasa (leukoderma), Visuchi (cholera), and Unmada (psychosis).

Three types of factors for the manifestation of diseases have been mentioned in the Vedas under following headings: Accumulated toxins in the body (Ama), krimi (parasites), and Tridoshas (three biological energies).

Eight branches (Ashtanga Ayurveda) of therapeutics in Ayurveda are seen to have precursors in Vedas. For example, the branch of danshtra (toxicology), which deals with exposure to poisons, mentions two groups of poisonous substances: Sthavara visha (toxic substance of plant origin), Jangama visha (toxic substance of animal origin).

Vedic literature shows that people of that era had a clear understanding of properties, signs,and symptoms of poisoning and had formulated and used antidotes effectively. Management of snakebite, for example, involved herbal remedies, precious stones, and incantations.This approach is still in practice among folk healers.

According to Vedic philosophy, the two fundamental purposes of life on earth are longevity and reproduction. These concerns are reflected in the attention given to rasayana (anti-aging and geriatrics) and to vajeekarana (aphrodisiacs) throughout the Vedas.

The literature also features narrative accounts of rejuvenation, such as the story of the sage Chyavana regaining his youth following treatment by the Ashwini (twin celestial physicians).

The Vedas describe many surgeries performed by the Ashwinis and documents surgical techniques that seem remarkably prophetic. References to shalya (surgery) include the following: Use of a prosthesis to replace the amputated lower limb of Vishphala,who lost her leg in a battle. A prosthesis was made of iron and installed surgically. Surgically replacing the severed head of Dakshaprajapathi,with a goat head to restore his life.

The Vedas also praise the obstetrical and gynecological skills of Vedic physicians such as Susha, Vishkala, Saraswati, and Savitri and describe their pregnancy care, childbirth and infant care practices in detail:

Setting up a labor room along with equipment required, the steps involved in labor, and the management of complications are elaborated in the Atharva Veda. Among the labor positions, dorsal position is recommended during the labor to facilitate childbirth. Rituals and specific herbal remedies during and after the childbirth are also described.

To relieve complications of childbirth such as puerperal fever, spiritual practices are performed along with certain oblations. In case of a breech delivery of the infant, a set of austerities are performed by the caregiver so as to counteract the ill effects.

There is mention of artificial respiration for asphyxia neonatorum, using oral tubing to resuscitate the infant.

Specific information regarding infertility due to female reproductive system infection is also explained.

Daily routine and sadvritta prakarana (section on good conduct): Vedic literature and rituals promoted a positive way of life through good conduct in thought, action,and communication. The details of this code of conduct are enumerated and its benefits reiterated throughout the Vedic literature.Conduct for mental hygiene is also explained.Societal values and social behavior were strongly influenced by Sanskrit precepts such as the following: Matru devo bhava, pitru devo bhava, Acharya devo bhava, Atithi devo bhava (“Mother is divine, so is the father, and the teacher, divine are the guests that come my home”).

Spiritual healing or using divine austerities to relieve various maladies is seen as the most common practice. A number of rituals involving chanting, oblations, fasting, gemstones, and fire ceremonies can be seen in the Vedas as remedies for both physical and mental disorders.A priest or the holy man facilitated the healing by invoking the Gods, kindling a ceremonial fire, and offering necessary austerities.

Using the natural elements is the specialty of Rig Vedic healing. This text attributes divine healing powers to the natural resources detailed in the following list:

Sun exposure was believed to alleviate disorders such as parasites/worms, cardiac problems, anemia, and jaundice.

Water was said to have the most powerful healing properties. Its life-sustaining and growth-promoting qualities were believed to hold miraculous therapeutic properties.

The fierce quality of fire is mentioned as destroyer of visible and invisible parasites and was applied in various morbid conditions involving cold and stagnation.

Flowing air was thought to increase the life force, and its expansive quality was said to have tremendous healing power.

In conclusion, all these previously outlined features of the Rig Veda and subsequent volumes of the Vedas provide strong evidence of a deep connection between Ayurveda and the entire body of Vedic literature. Indeed,the earliest foundations of Ayurveda’s natural approach to medicine and health promotion were laid down in their preliminary form in the Rig Veda. This first volume of the canon even includes a hymn (Oshadhi sukta) entirely dedicated to herbs and dietary substances.Extensive evidence likewise supports the belief that the Atharva Veda is the direct precursor of Ayurvedic Medicine. This relationship is borne out in the Atharva Veda’s many references to the nature, causes, and pathophysiology of disease; to disease management practices; and to the structure and functions of the human body, as well as in this Veda’s focus on the both the spiritual and rational aspects of health, all of which prefigure the fundamental concerns of Ayurveda.

The large collection of texts known as the Upanishads can be considered elaborations on the earlier Vedas. Among the most important of these approximately 108 works are the Katha,Mundaka, Isa, Aitareeya, Brihadaranyaka,Taittiriya and Chandogya Upanishads. The two earliest, the Brihadaranyaka and the Taittiriya Chandogya, were composed before Buddhist period, between 800 BCE and 100 CE.

Like the Vedas, the Upanishads consider living human beings as synthesis of body, mind, and soul. They also contain extensive references to spiritual healing practices and other healing modalities. The idea of prana as the life force that supports and sustains nature as well as the human body feature prominently.The Upanishads detail methods of enhancing the abundance of prana in order to protect health and promote longevity. They specify five types of vata, governed by prana (i.e., prana vata , udana vata , samana vata , vyana vata , and apana vata ) that regulate all bodily functions.When properly controlled through spiritual breathing exercises, prana was said to awaken the kundalini energy that enables individuals to experience the higher self.

Digestive fire, or agni, is represented in the Upanishads as a conveyor of offerings to the higher self and sustainer of life that, when offered wholesome food, brings about clarity of thought and enhances lifespan. Fasting as a spiritual practice to promote health was in wide practice during this era as much as the use of a wholesome diet and herbs to enrich body, sense organs, and mind and to achieve longevity.

The Upanishads also continued the Vedic tradition of describing various plants that were used for healing and spiritual purposes,including the ashwatha and Nyagroda , which were worshiped as eternal trees that enhanced health and spiritual well-being.

At the turn of 4 th century CE, Purana literature emerged and began disseminating Vedic knowledge in the form of mythological narrations that glorify Vedic lifestyle and spiritual practices. The main purpose of these texts, which total 18, was to motivate people toward meditation, righteous living, health, and longevity.

In terms of health information, the Puranas describe the mythological origins of certain health conditions such as fever, skin ailments,and wasting diseases. Fundamental doctrines of Ayurveda like five elements and tridosha theories are explained in the Padma Purana.

Other Puranic literature details the healing properties of certain dietary preparations, herbs,precious metal, and gemstones. This information both draws on and adds to knowledge preserved in the Vedas and Upanishads.

The Vishnu Purana also provides daily and seasonal routines for health promotion and a code of conduct for a positive lifestyle. The Skanda Purana describes the qualities of an ideal Ayurvedic physician as well as a code of ethics and the setup required for a successful Ayurvedic practice.

Thus, the Puranas present a spiritually driven healthcare model aimed at delivering physical and mental well-being.

Buddhist literature suggests that this philosophy had a major impact on the development of Ayurveda:

Buddha himself was referred to in the literature as the Maha Bhishak (“greatest physician”), as he showed the path of liberation from disease and death.

The Taittiriya (c. 200 BCE), the oldest treatise of Buddhism, talks about native medicine in Buddhist tradition.

The Navanitaka (a.k.a. the Bowers Manuscript) provides a glimpse of a Buddhist version of Ayurvedic healing.

The Saddharma Pundarika Sutra (c. 1 st century CE) mentions that special nursing homes attached to flower gardens, with good infrastructure for healing, were used for diagnosis and treatment of illness.

Ayurveda had an equally profound impact on Buddhism. Buddhist literature shows that the Buddhist theory of disease draws directly from Ayurvedic principles. Diseases were classified as follows: originating from imbalance of vata dosha, originating from imbalance of pitta dosha, originating from imbalance of kapha dosha, and originating from imbalance of all three doshas ( sannipatika ).

Formulations of herbs such as the following were also in wide use: freshly expressed juices,pastes, decoctions, cold infusions, and hot infusions.

The pancha mahabhuta (five elements) theory is explained in Buddhist literature, and the word dhatu (primitive matter), serving as the equivalent to mahabhuta (elements), is used to represent the basic unit of matter that forms all structures in nature, including the human body. In the Suvarna Prabha Sutra,the influence of the seasons on health and the need for seasonal adjustments in lifestyle and diet changes are explained. The literature also elaborates on the anatomical and physiological features of many organs and organelles. The Buddhist scripture the Vinaya Pitika adapts the eight limbs of Ayurveda that were already developed and in practice to the Buddhist way of life and values. Buddhists and Hindus alike revered, the ancient university Takshashila, and its life science curriculum included Ayurveda.

The Ayurvedic concept of the six tastes and its utility in disease management was also popular among Buddhist healers. It is documented that the renowned physician Jeevaka administered some of the purification procedures used in Ayurvedic panchakarma (five cleansing procedures) therapy to the Buddha himself, and prescribed a special post detoxification diet afterward.

In the Vinaya Pitaka , there are references to a remedy called pancha bheshaja , a combination of five substances that promote health and manage diseases by pacifying the three doshas: ghee and butter (alleviates pitta),oil (reduces vata), and honey jaggery (pacifies kapha).

A later text, the Milinda Prashna , describes the same combination as an antidote for poisoning. In the same text, tridosha theory serves as the basis for understanding the pathophysiology of disease. This theory is explained in the form of a dialogue between a Greek king, Milinda, and his teacher, the Buddhist sage Nagasen, who sorted the causes of diseases into eight categories: Vata imbalance,Pitta imbalance, Kapha imbalance, imbalance of sannipata (all three dosha), seasonal influences,irregular diet, improper treatment, and past deeds.

As Buddhist teachings spread, a refined form of Ayurveda reached distant nations.Along with other ancient Indian knowledge systems such as astrology and architecture,Ayurveda became part of the repertoire of scholars that traveled abroad.

This era is considered the golden age of Ayurveda. In the early days of Ayurveda, its principles were transmitted orally by sages who shared the knowledge they had intuited while deep in meditation with their disciples. During the Samhita period, this knowledge was codified in the classic works of Ayurvedic literature, and the main therapeutic branches emerged as full fledged schools of medicine, such as Athreya (internal medicine), Dhanvanatari (surgery),and Kashyapa (pediatrics).

Although each of the samhita focused on one specialty, these works concisely conveyed the basics of all eight therapeutic branches of Ashtanga Ayurveda. Compilations that covered all the branches were entitled samhitas .Students who initially concentrated on any one of the branches ultimately gained the gist of all of them. Each of these specialties advocated the same basic approach of treating prevention and cure as its two equally important aims.Rulers of this period encouraged the growth and development of Ayurveda.

The three major compilations: Charaka Samhita , Sushruta Samhita , and Ashtanga Sangraha and Ashtanga Hridaya .

Charaka Samhita This is the earliest major medical text of Ayurveda, attributed to the physician Charaka. Although traditionally he is thought to have lived around during the period between 1000 and 800 BCE, most Western scholars now place him around the 1 st century CE, when the Charaka Samhita probably reached its present form. The work contains the basic philosophy of disease, based on an imbalance of the three humors (vata, pitta,and kapha). The Charaka Samhita catalogs the following fundamental aspects of medical philosophy, medical care, and treatment:

Sutra (aphorism) — origin of Ayurveda,general principles, and philosophy.

Nidana (diagnosis) — causes, and symptoms of disease.

Vimana (measure) — many subjects,including physiology, methodology, and ethics.

Sharira (body) — anatomy, embryology,metaphysics, and ethics.

Indriya (sense organ) — prognosis.

Chikitsa (treatment) — therapeutics.

Kalpa (preparation) — pharmacy.

Siddhi (success in treatment) — purification therapy.

The Charaka Samhita contains 120 adhyayas (chapters), divided into 8 parts: Sutra Sthana (30 chapters), Nidana Sthana (8 chapters), Vimana Sthana (8 chapters), Sharir Sthana (8 chapters), Indriya Sthana (12 chapters), Chikitsa Sthana (30 chapters), Kalpa Sthana (12 chapters), and Siddhi Sthana (12 chapters).

Commentaries on the Charaka Samhita : Dridabala — 4 th century CE, Chakrapani —11 th century CE, and Gangadhara — 16 th century CE.

Sushruta Samhita In his compendium of surgical procedures, Sushruta mentions that his teacher and surgical mentor was Divodasa,the king of Kashi, who was considered the incarnation of Lord Dhanvanthari, the physician of the gods. Ancient texts recognized Sushruta as son of the sage Vishwamitra. He was reputed to have written his treatise in Varanasi(Banaras) sometime between 600 and 200 BCE.It was through Sushruta’s accomplishments that surgery achieved a leading position in general medical training.

The Sushruta Samhita contains discussions of surgical equipment; a classification of abscesses; and treatments for burns, fractures,and wounds, as well as instructions for amputation. It gives a complete description of human anatomy, including bones, nerves,blood vessels, and the circulatory system,and it mentions the brain as the center of the senses. Sushruta’s treatise describes anatomical dissection and details surgical techniques that were the most advanced in the world at the time of their recording.

The text is divided into two parts, each comprising several sections: the Purva-tantra ( Sutra-sthana , Nidana-sthana , Sarira-sthana , Kalpa-sthana , and Chikitsa-sthana ); the Uttara-tantra ( Salakya Kaumarabhrtya , Kayacikitsa ,and Bhutavidya ).

In addition to surgery ( shalya and salakya ) ,those two parts together encompass specialties such as general medicine; pediatrics; geriatrics;diseases of the ear, nose, throat, and eye;toxicology; aphrodisiacs; and psychiatry. Thus the complete samhita, despite its devotion to the science of surgery, manages to incorporate the salient portions of numerous other disciplines as well.

Sushruta describes 9 types of surgical procedures:

Chedana (excision) — the surgical removal of a part or whole of the limb.

Bhedana (incision) — a cut made in the flesh to achieve effective drainage or to expose underlying structures.

Lekhya (scraping) — the removal by scraping of scooping out material such as a growth, flesh of an ulcer, or tooth tartar.

Vedhya (puncturing) — piercing tissue with a special instrument ( vyadhana ) to drain veins, hydroceles, or ascitic fluid in the abdomen.

Esya (exploration) — probing sinuses and cavities to locate foreign bodies and determine their size, number, shape, position, and condition.

Visravaniya (evacuation of fluids).

Ahrya (extraction).

Sravana (blood-letting) — draining blood from the body to treat skin diseases, abscesses( vidradhis ), localized swelling, etc.

Svana (suturing) — sewing together the flaps of a wound or surgical incision.

Sushruta also classifies the different bones and characterizes their reaction to injuries.Various dislocations of joints ( sandhimukt a ) and fractures of the shaft ( kanda-bhagna ) are systematically described.

He also describes over 120 surgical instruments, 300 surgical procedures, and identifies 8 categories of surgery in categories,including plastic surgery operations. The earliest of these types of procedure probably involve nasal reconstruction.

He enumerates 107 marma points that are essential for healing injuries, identifying their structure, anatomical location, and complications due to their injury.

Ashtanga Sangraha and Ashtanga Hridaya Two separate authors with the same name,Vagbhata I (c. 2 nd century CE) and Vagbhata II(c. 7 th century CE) are considered the respective authors of the Ashtanga Sangraha and the Ashtanga Hridaya.

Where does the word Ashtanga start for 8 branches of Ayurveda?

In the Ashtanga Sangraha, Vagbhata I, or Vridda Vagbhata, a Mahayana Buddhist, edited content from earlier texts and arranged it in a well-organized format. Similar to Sushruta’s text, there are two major divisions of the text,namely, the Poorva (introductory section) and the Uttara (treatment section). The author combined relevant sections from Charaka and Sushruta’s writings with his own work to create a comprehensive text.

The Ashtanga Sangraha has six sections with 150 chapters. The number of chapters in each section is as follows:

Sutra (introductory section) — principles of Ayurveda, preventative care, dietetic principles,and therapeutic methods.

Sharira (body section) — embryology,anatomy, and physiology.

Nidana (diagnosis section) — causes and symptoms of disease, and pathogenesis.

Chikitsa (treatment section) — line of treatment of disease, herbal prescriptions,dietetics and patient care.

Kalpa (formulations section) — formulations for cleansing procedures.

Uttara (second half) ENT and ophthalmology,toxicology, geriatrics, and general surgery.

The text deals exclusively with the etiology,symptomatology, and therapeutics of disease.

The conciseness of Vagbhata I ’s work makes it clear that the author has no patience for irrelevant content, does not elaborate on any unnecessary information, and shuns unnecessary repetition.

Vagbhata II edited and reorganized Ayurvedic knowledge from other texts in a simple and student-friendly fashion. In the Ashtanga Hridayam , he remarks that earlier text(i.e., the Ashtanga Sangraha ) was composed by collecting only the relevant and important information from the other works. The Ashtanga Hridayam provides an even more refined knowledge of Ayurveda that is highly beneficial for students.

The title Ashtanga Hridaya means “the heart of eight branches of Ayurveda”. Due to its popularity, the text was translated into the Arabic,Persian, Tibetan, and German languages.

The Ashtanga Hridayam is divided into six sections and has a total of 120 chapters.The number of chapters in each section is as follows:

Sutra (introductory section) — 30 chapters dealing with principles of Ayurveda, preventative care, dietary principles, and therapeutic methods.

Sharira (body section) — 6 chapters dealing with embryology, anatomy, and physiology.

Nidana (diagnosis section) — 16 chapters that deal with causes and symptoms of disease and pathogenesis.

Chikitsa (treatment section) — 22 chapters dealing with a line of treatments for disease,herbal prescriptions, dietetics, and patient care.

Kalpa (formulations section) — 6 chapters explaining formulations for cleansing and detoxification procedures.

Uttara (second half) — 40 chapters dealing with pediatrics, psychiatry, ENT and ophthalmology, toxicology, geriatrics, and general surgery.

The three minor compilations: Madhava Nidhana , Sharnagadhara Samhita , and Bhava Prakasha .

Madhava Nidana Written in the 7 th century BCE by Madhavakara, the son of Indukara, this compendium of information pertains exclusively to pathology. In addition to quoting earlier works by Charaka, Sushruta,and Vagbhata, the author offers his views on specific pathologies.

The layout of the content is based on the five categories of pathogenesis:

Nidana — the factors responsible for producing disease (i.e., etiological factors).

Purvaroopa — the warning signs of disease that arise as doshas (bio-energies) become aggravated.

Roopa — the manifestation of disease with prominent clinical features.

Upashaya — aggravating and relieving factors.

Samprapti — the entire process of manifestation of disease.

There are 69 chapters in the text: Chapters 2~19, 22~37, and 49~54 deal with pathologies of diseases explained under kaya chikitsa (internal medicine); Chapters 20 and 21 explain pathology of pathologies of diseases explained under bhutavidya (psychiatry); Chapters 38 and 55 discuss pathologies of diseases explained under shalya (surgical conditions);Chapters 56~60 deal with pathologies of diseases explained under shalakhya (ENT and ophthalmology); Chapters 61~68 enumerate the pathologies of pathologies of diseases explained under kaumara brithya (pediatrics); Chapters 69 explains pathologies of pathologies of diseases explained under agada tantra (toxicology).

Sharangadhara Samhita Compiled around 12 th century CE, by Sharangadhara, this work has 32 chapters and 2,600 verses. The author has systematically arranged information on Ayurvedic pharmacy. It is one of the most important contributions to the field of Ayurveda,as earlier texts had not yet organized formulation methods that systematically progressed from simple preparations to compound formulations.

Sharangadhara’s text has three sections:

Section 1 — anatomy, pathophysiology,basic principles, pulse diagnosis, pharmacological actions, weights and measures.

Section 2 — extensive information on pharmacy with specific examples of formulations for various pathologies, including detailed instructions on alchemical preparations.

Section 3 — formulations used in detoxification procedures and method of administration, diseases of the head and neck region.

Concepts of Pharmacy in second section of Sharangadhara’s text:

Chapter 1 — Swarasa Kalpana (freshly extracted juice) and examples.

Chapter 2 — Kwatha Kalpana (herbal concoction) and examples.

Chapter 3 — Phanta Kalpana (hot infusion) and examples.

Chapter 4 — Hima Kalpana (cold infusion) and examples.

Chapter 5 — Kalka Kalpana (herbal paste) and examples.

Chapter 6 — Choorna Kalpana (herbal powders) and examples.

Chapter 7 — Gutika Kalpana (pills) and examples.

Chapter 8 — Avalehya Kalpana (herbal jams) and examples.

Chapter 9 — Sneha Kalpana (herbal oils and ghee) and examples.

Chapter 10 — Sandhana Kalpana (fermentative preparations) and examples.

Chapter 11 — Dhatu Shodhana Marana (mineral and metal purifications).

Chapter 12 — Rasa Shodhana Marana (purification of mercury).

Bhavaprakasha Bhava Mishra is the 16 th century CE author of the Bhavaprakash . This significant work focuses primarily on materiamedica. The text stands as a historical landmark since it reflects the state of Ayurvedic Medicine at the transition from the medieval to modern times. The contents of the Bhavaprakasha was compiled from earlier texts; however, the author has contributed a significant amount of information regarding medicinal substances.

This comprehensive guide to a successful Ayurvedic practice has three voluminous sections:

Part 1 (7 chapters) — discusses the origins of Ayurveda, the evolution of life and cosmology, embryology, anatomy, preventive science, and the properties and actions of herbs.

Part 2 (70 chapters) — details the etiopathogenesis of several diseases and their management.

Part 3 (2 chapters) — discusses geriatrics and aphrodisiacs.

Medieval times in India extended from the start of the 6 th century CE until the beginning of the 16 th century CE. Influenced by religious conflicts, the development of Ayurveda was limited at this period. Prior to this time, Ayurveda had received strong support from Indian kings and emperors. Ayurvedic practitioners served as court physicians, and royal treasuries subsidized the practice and development of the science. Resources were provided to advance strategies not only for the health of the royal family but also for the entire kingdom. With the coming of foreign rulers,however, the progress of Ayurveda languished.Muslim rulers attempted to squelch Ayurveda in order to patronize the Unani system of medicine and other forms of Greco-Arab Medicine;Ayurveda was treated like an unwanted stepchild. This situation persisted until the assumption of the throne by Firoz Tughlaq at the beginning of 14 th century, when Muslim rulers began to appreciate the importance of Ayurveda and take steps to patronize it.

The survival of Ayurveda during this period, and later under British rule, stemmed from its close entwinement with Indian culture. In fact, the Unani system of medicine introduced by the Mughals had to borrow and incorporate concepts of Ayurveda for its own good. Because Ayurveda was a rich and widely valued science, the Unani system needed to draw from it to expand its knowledge base and broaden its appeal. Eventually, the two systems came to co-exist. Ayurvedic vaidyas and Unani practitioners ( hakims ) were accorded equal status and encouragement, even though the hakims easily outnumbered the vaidyas.Ayurvedic texts were translated into the Persian language and Ayurvedic medical knowledge spread to the Middle East and Europe. Kings like Akbar and Jahangir built hospitals and encouraged the practice of Ayurveda.

An important, rather a peculiar medical development in medieval India is the increasing number of compilations of materia-medica knowledge. Known as nigantu (lexicons),these compilations systematically grouped diet, herbal, and mineral substances for easy reference. Identification, location, morphology,and qualities along with their actions of various medicinal substances are collected and arranged according to different rationales. To date,there are 57 nigantus from various medieval periods. This effort remained a trend even during British rule. Nigantus seems to be the genuine and persistent attempt by the Ayurvedic scholars of the time to resolve the confusion regarding correct identification and application of medicinal substances.

Colonial rule in India extended from 1757 to 1947. During this time, except few small kingdoms, the entire Indian subcontinent was governed by the British Empire. This period saw a resurgence of doctors in India. Various levels of Western medical education were provided in local languages in the beginning and subsequently in English. There was a significant advancement in Western Medicine,and Ayurveda was regarded as a folk medicine.