作品选读

(Excerpt)

THE program of segregation was now instituted. One of its purposes was to protect loyal Japanese Americans from the continuing threats of pro-Japanese agitators. Tule Lake, one of the ten original centers, was chosen as the segregation center for the disloyal. In the fall of 1943 thirteen hundred Topazians (about one tenth of the total) were sent there. The group included all who had said they wished to return to Japan; the “No, nos,” that is, those who would not change their unsatisfactory answers to the questionnaire when they were given a chance to do so; all who remained under suspicion of disloyalty after investigation by the War Relocation Authority and the Federal Bureau of Investigation; and close relatives who would rather be segregated with their families than be separated from them.

Whatever decision was made, families suffered deeply. Children had to go to Tule Lake with their parents, but some adolescents resented the label “disloyal” and fought bitterly to remain behind.

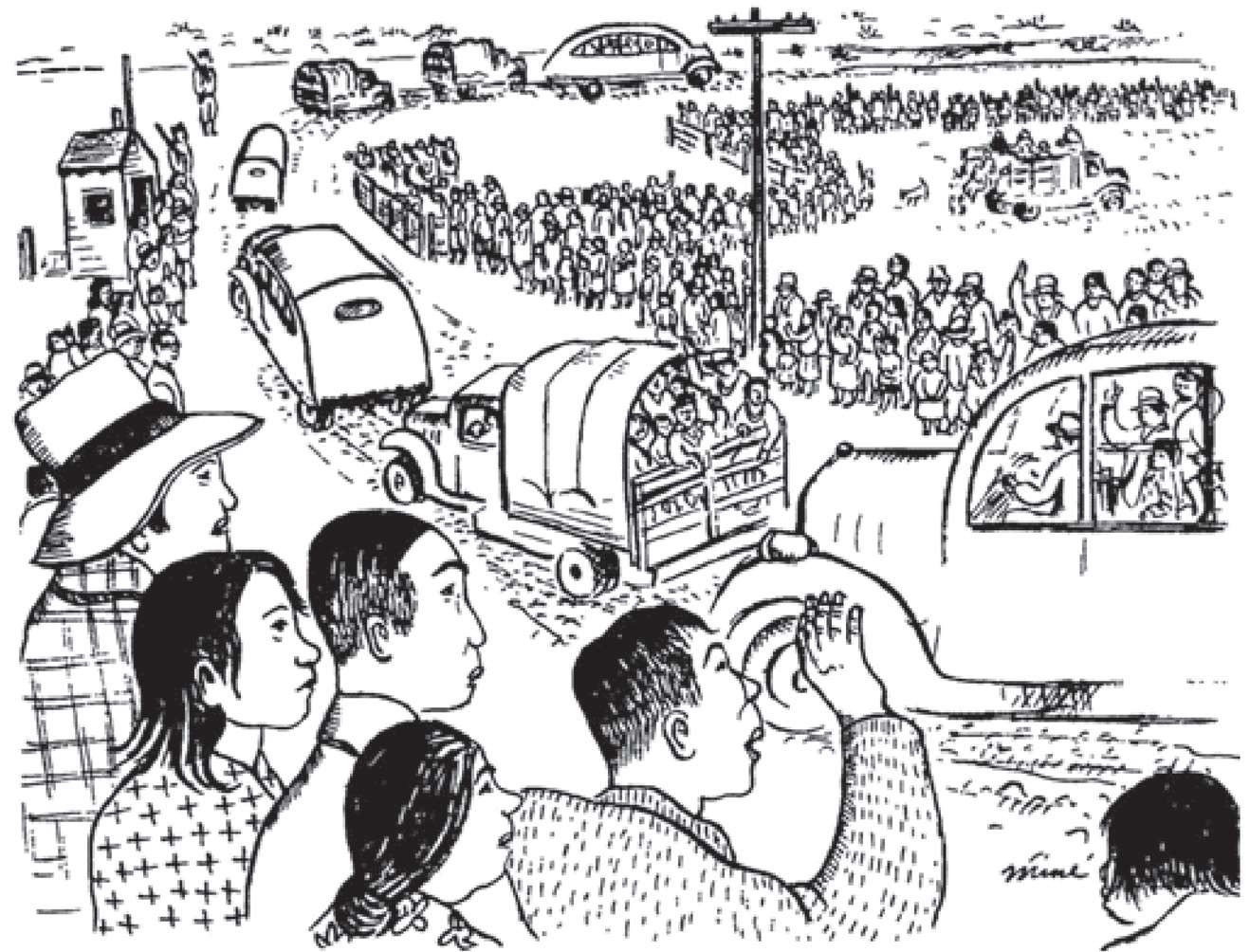

TWELVE hundred loyal citzens and aliens were transferred from Tule Lake to Topaz. Their arrival once more brought excitement to our now relatively peaceful city.

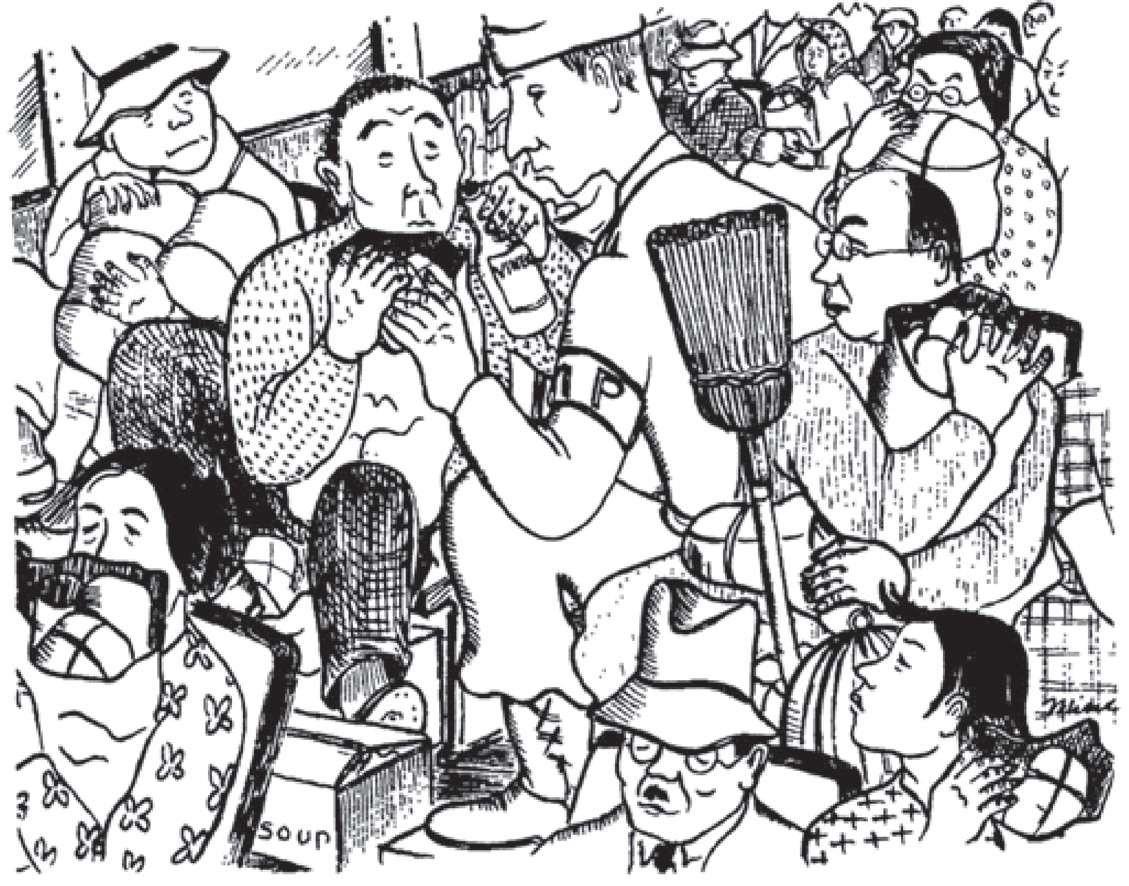

THE rules were becoming much less rigid. Block shopping was introduced, whereby a resident of each block was permitted to shop in the nearby town of Delta for the rest of the block. Special permits were arranged ahead of time by the administration. There was a thorough inspection by the military police both on leaving and returning.

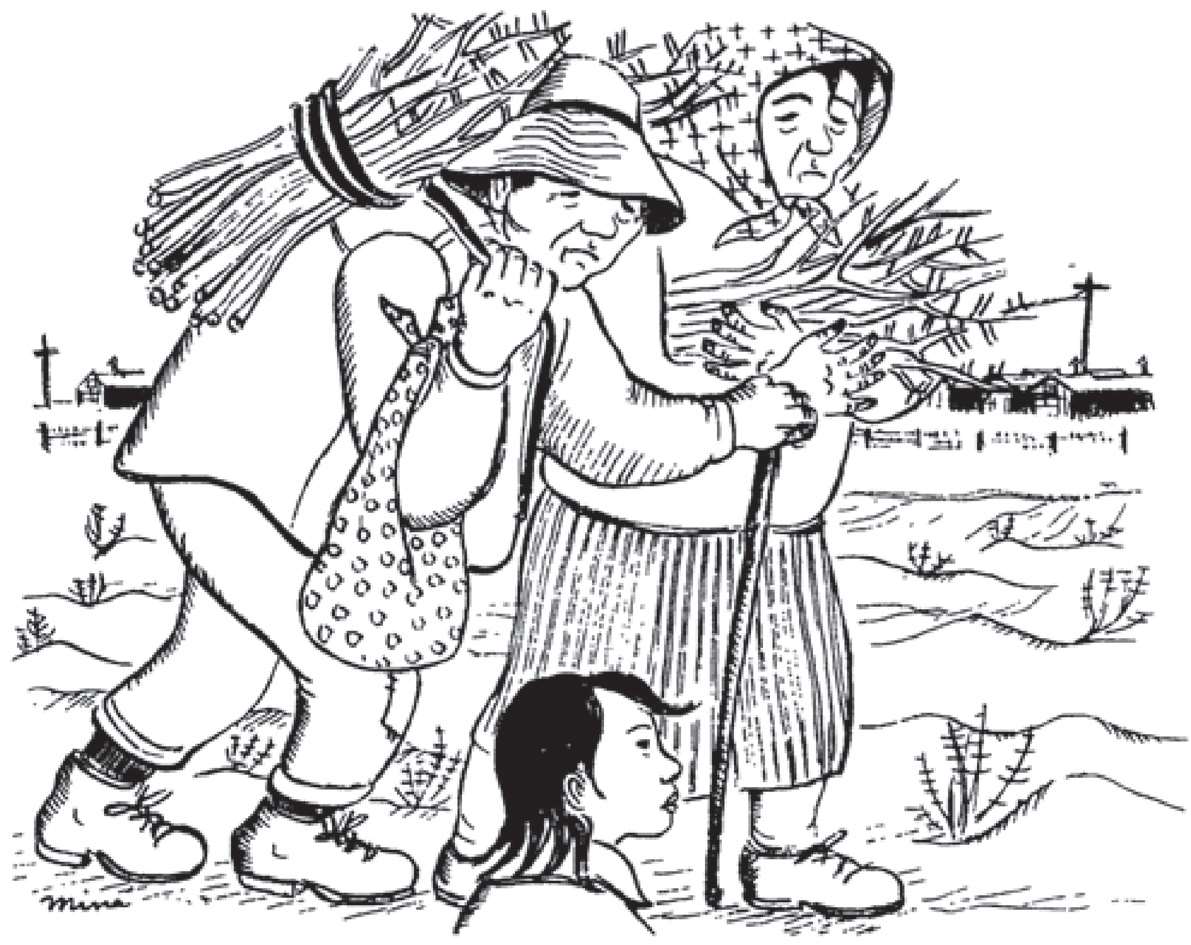

UNDER the change in rules, many now went outside the fences to the outer project area to gather vegetation and small stones for their gardens. Others hunted for arrow heads.

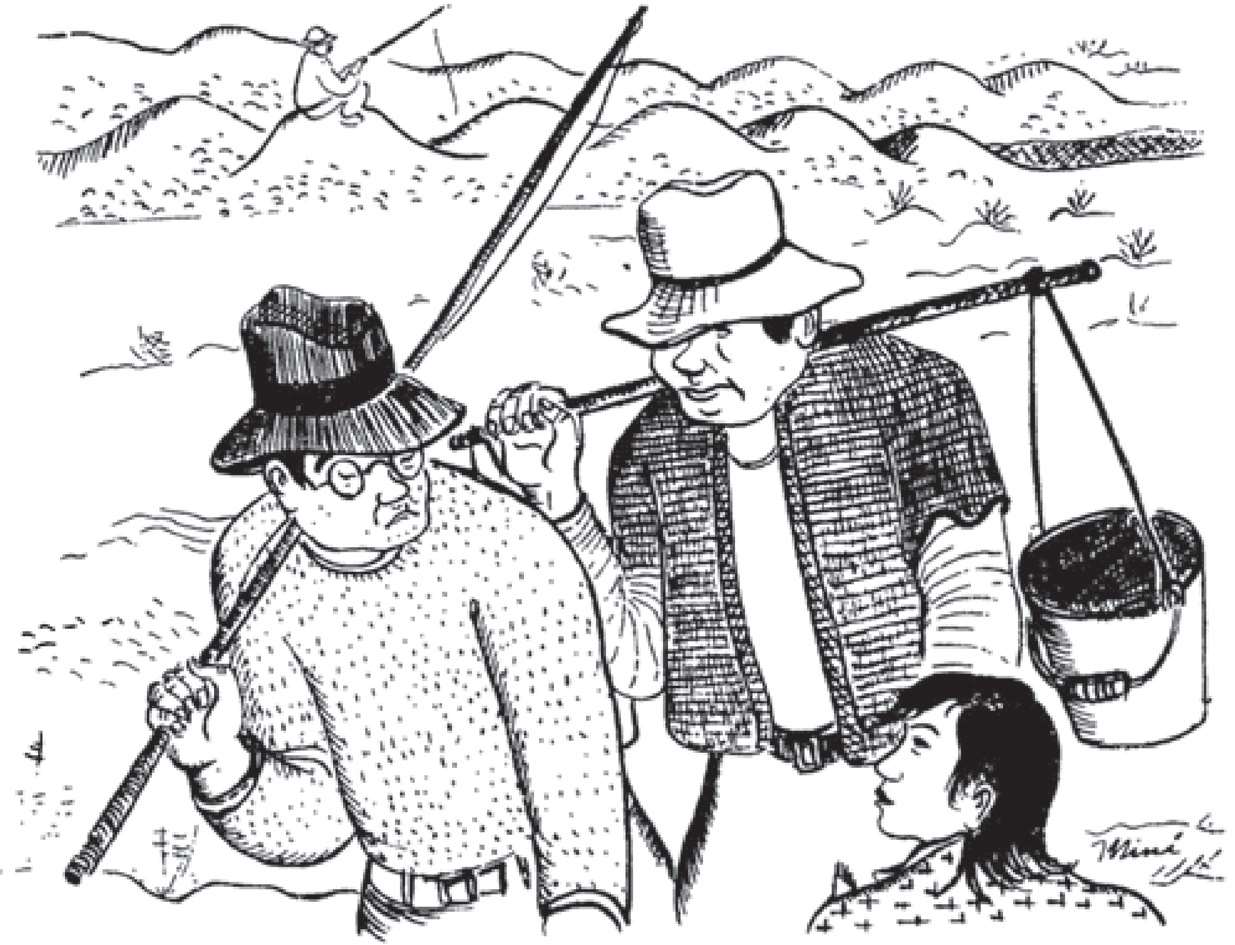

MANY went fishing in the irrigation ditches, about three miles away on the outskirts of the project’s agricultural area.

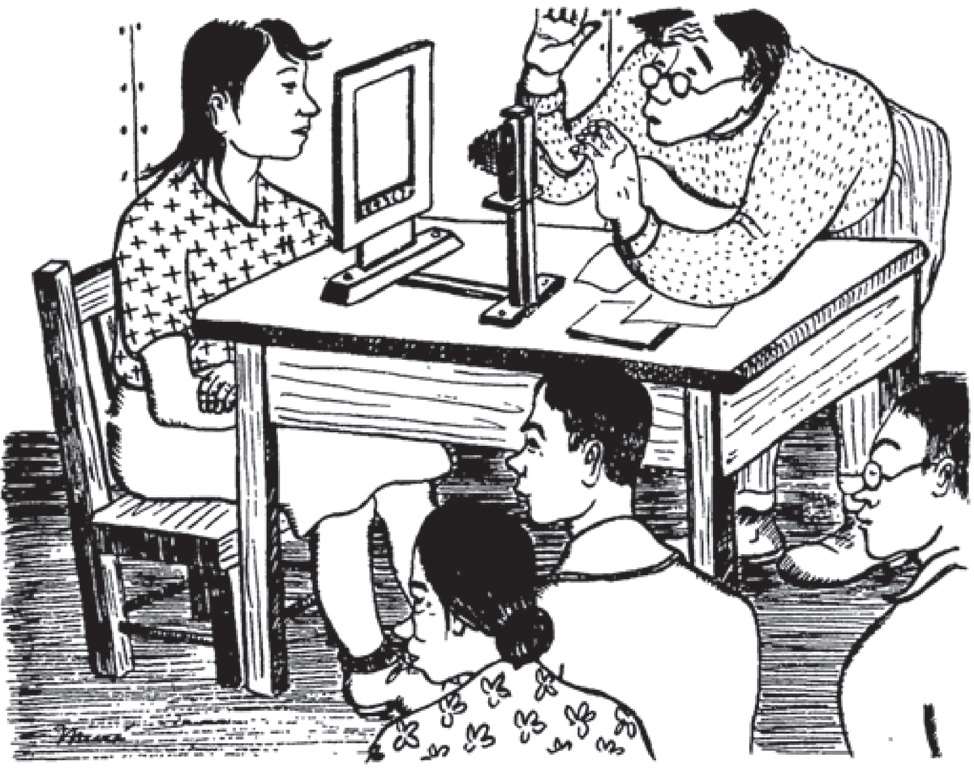

RELOCATION programs were finally set up in the center to return residents to normal life. Students had led the way by going out to continue their education in the colleges and universities willing to accept them. Seasonal workers followed, to relieve the farm labor shortage.

Many volunteered for the army. Government jobs opened up, and the defense plants claimed others. The Intelligence Division of the army and navy demanded still others as instructors and students. My brother had left in June to work in a wax-paper factory in Chicago. Later he was inducted into the army.

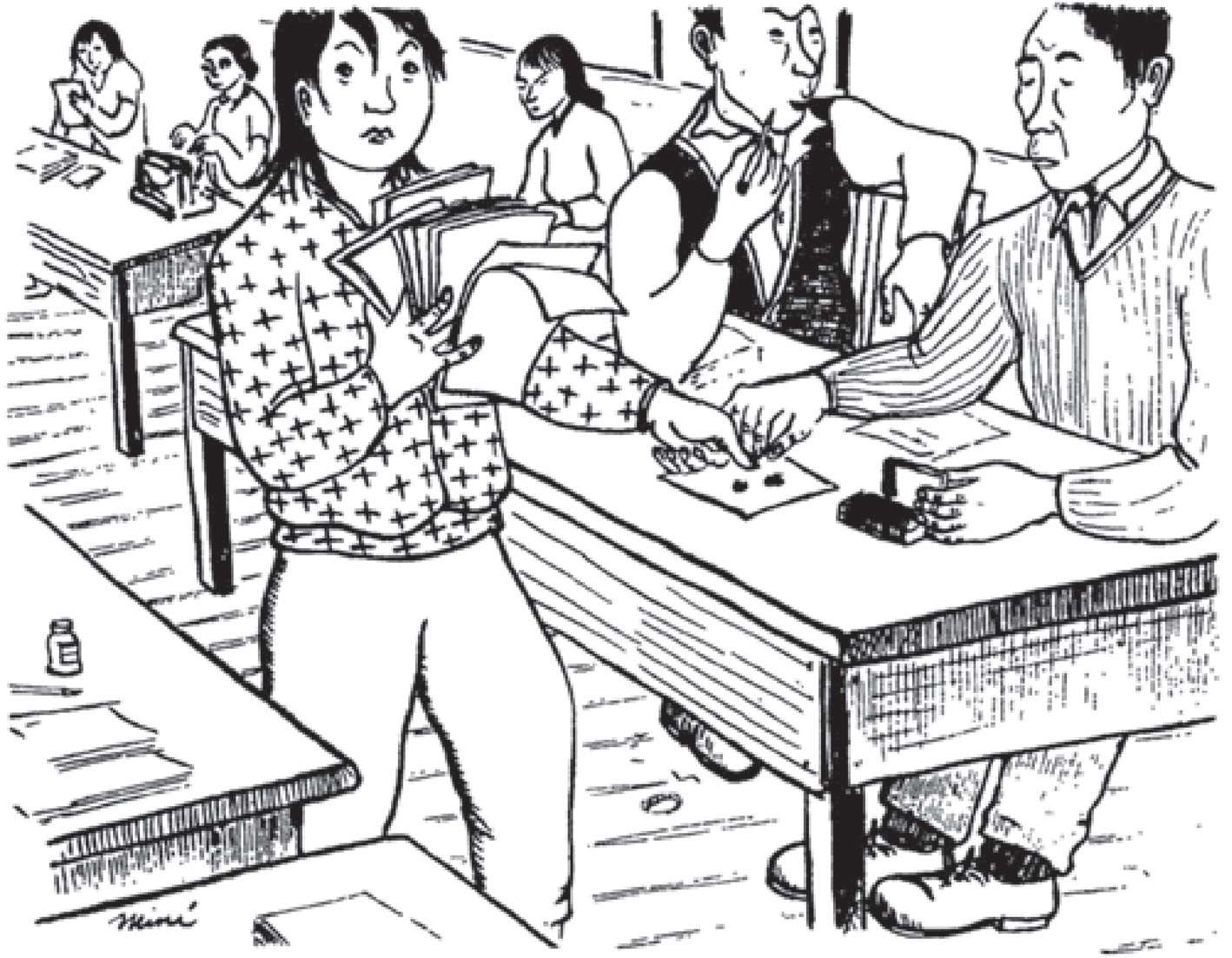

Much red tape was involved, and “relocatees” were checked and double checked and rechecked. Citizens were asked to swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and to defend it faithfully from all foreign powers. Aliens were asked to swear to abide by the laws of the United States and to do nothing to interfere with the war effort. Jobs were checked by the War Relocation offices and even the place of destination was investigated before an evacuee left.

In January of 1944, having finished my documentary sketches of camp life, I finally decided to leave.

AFTER plowing through the red tape, through the madness of packing again, I attended forums on “How to Make Friends” and “How to Behave in the Outside World.”

I was photographed.

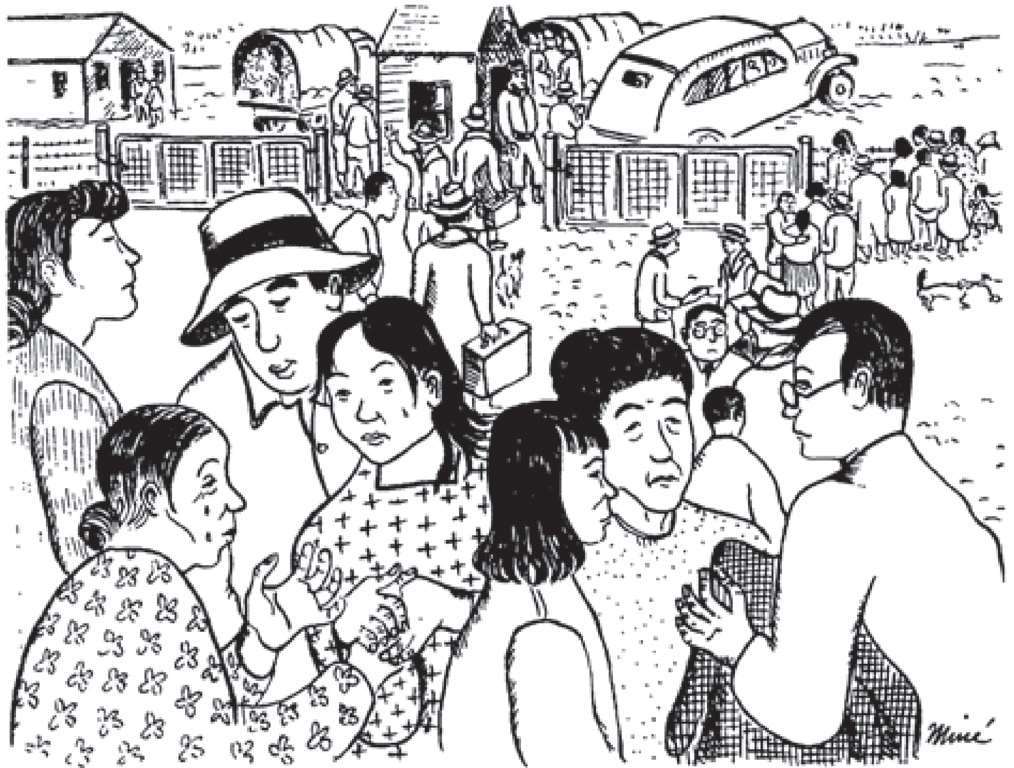

THE day of my departure arrived. I dashed to the block manager’s office to turn in the blankets and other articles loaned to me, and went to the Administration Office to secure signatures on the various forms given me the day before. I received a train ticket and $25, plus $3 a day for meals while traveling; these were given to each person relocating on an indefinite permit. I received four typewritten cards to be filled out and returned after relocation, and a booklet, “When You Leave the Relocation Center,” which I was to read on the train.

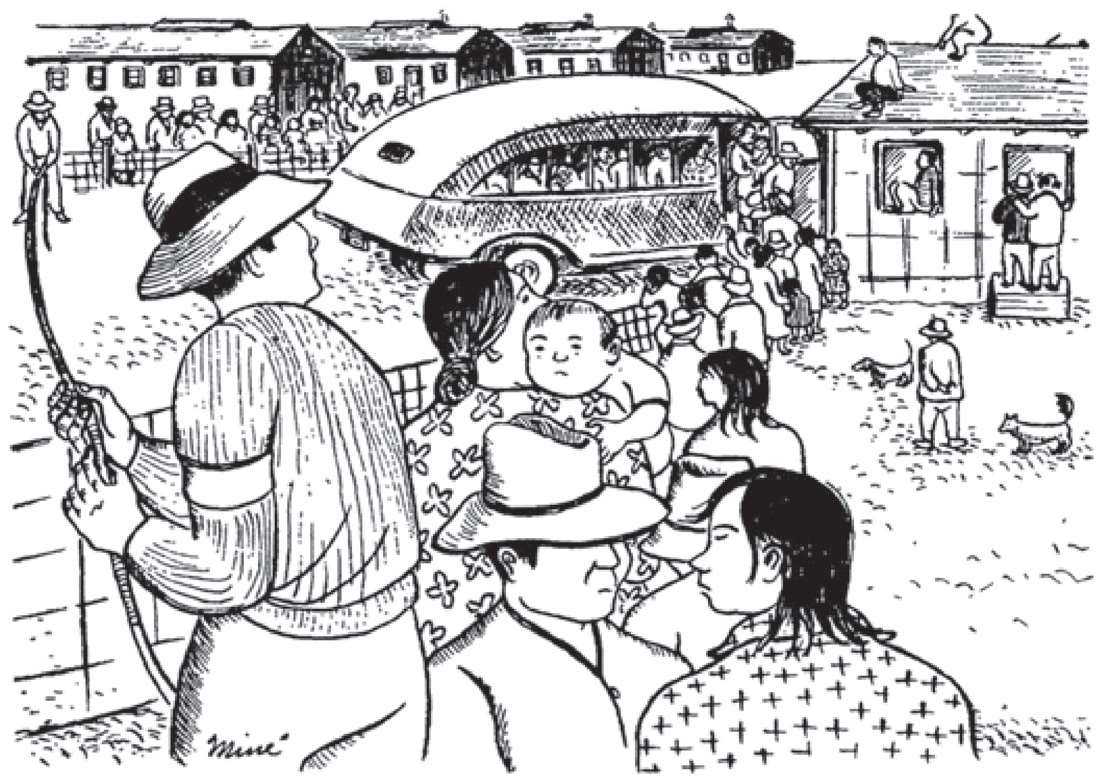

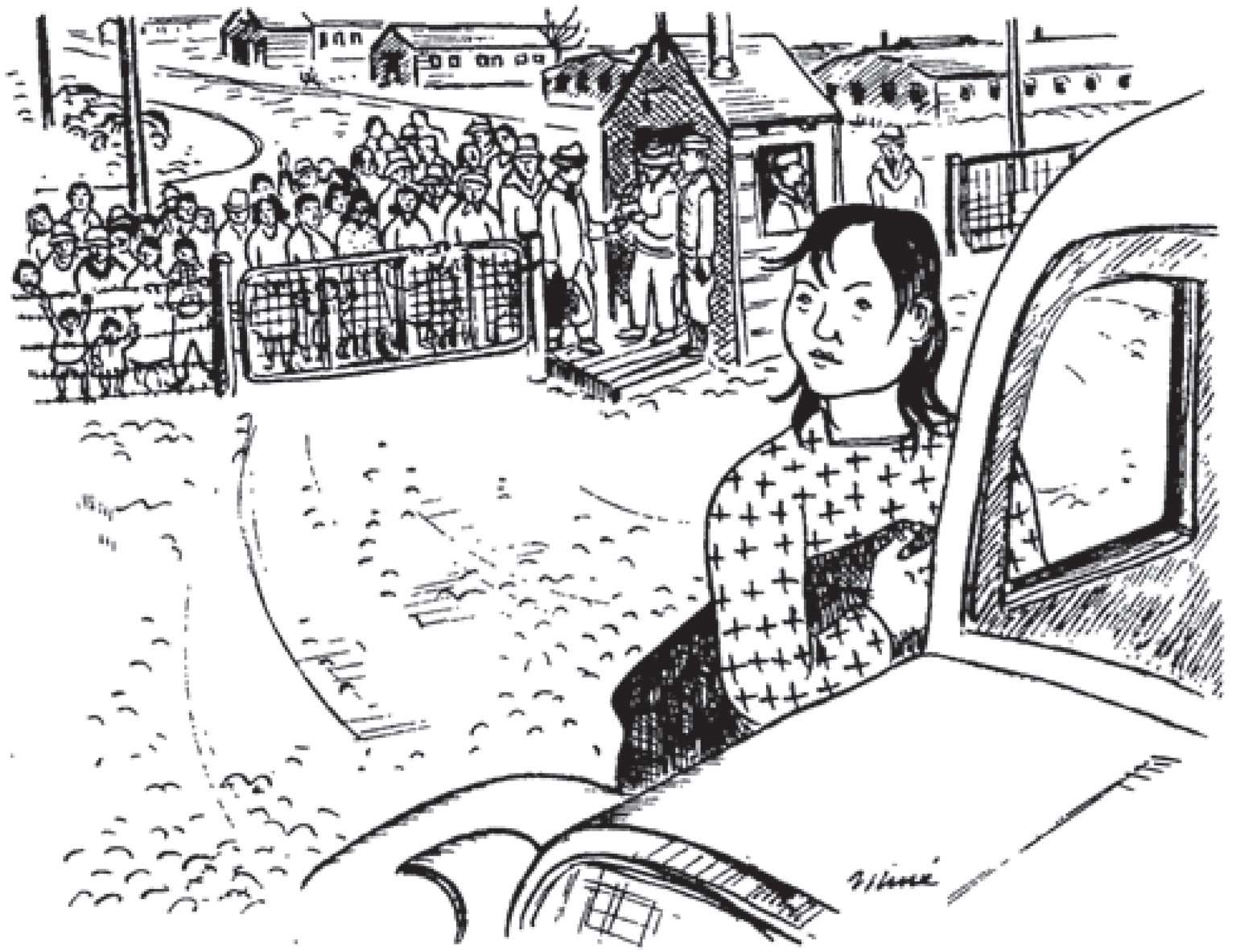

I dashed to the mess hall for a bite to eat, then to the Administration Office, picked up my pass and ration book at the Internal Security Office, and hurried to the gate. There I shook hands with the friends who had gathered to see me off. I lined up to be checked by the WRA and the army.

I was now free.

I looked at the crowd at the gate. Only the very old or very young were left. Here I was, alone, with no family responsibilities, and yet fear had chained me to the camp. I thought, “My...! How do they expect those poor people to leave the one place they can call home.” I swallowed a lump in my throat as I waved goodbye to them.

I entered the bus. As soon as all the passengers had been accounted for, we were on our way. I relieved momentarily the sorrows and the joys of my whole evacuation experience, until the barracks faded away into the distance. There was only the desert now. My thoughts shifted from the past to the future.