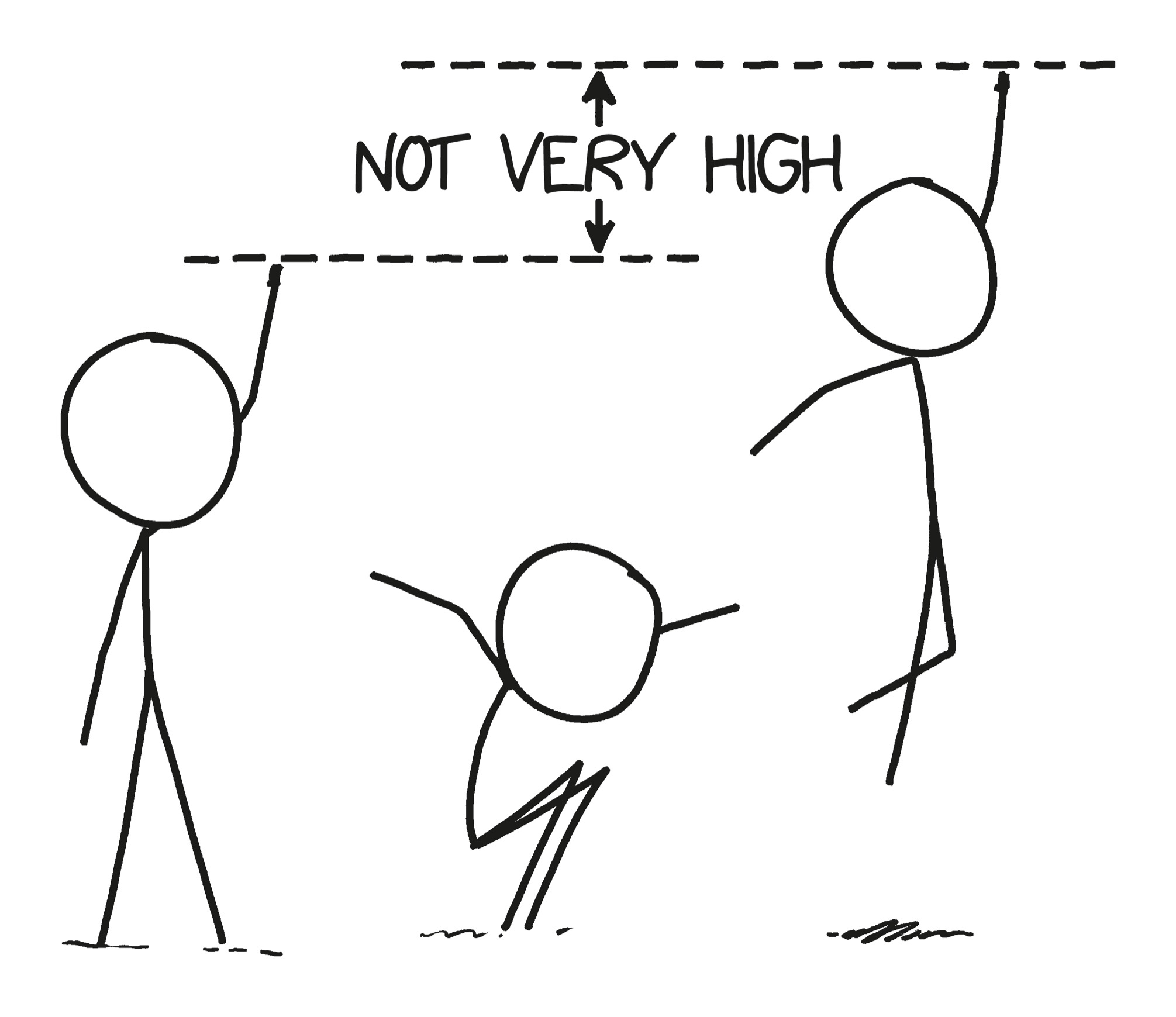

People can’t jump very high.

Basketball players make some impressive leaps to reach hoops placed high in the air, but most of their reach comes from their height. An average professional basketball player can only jump a little more than 2 feet straight up. Non-athletes are more likely limited to jumping a foot or so. If you want to jump higher than that, you’ll need some help.

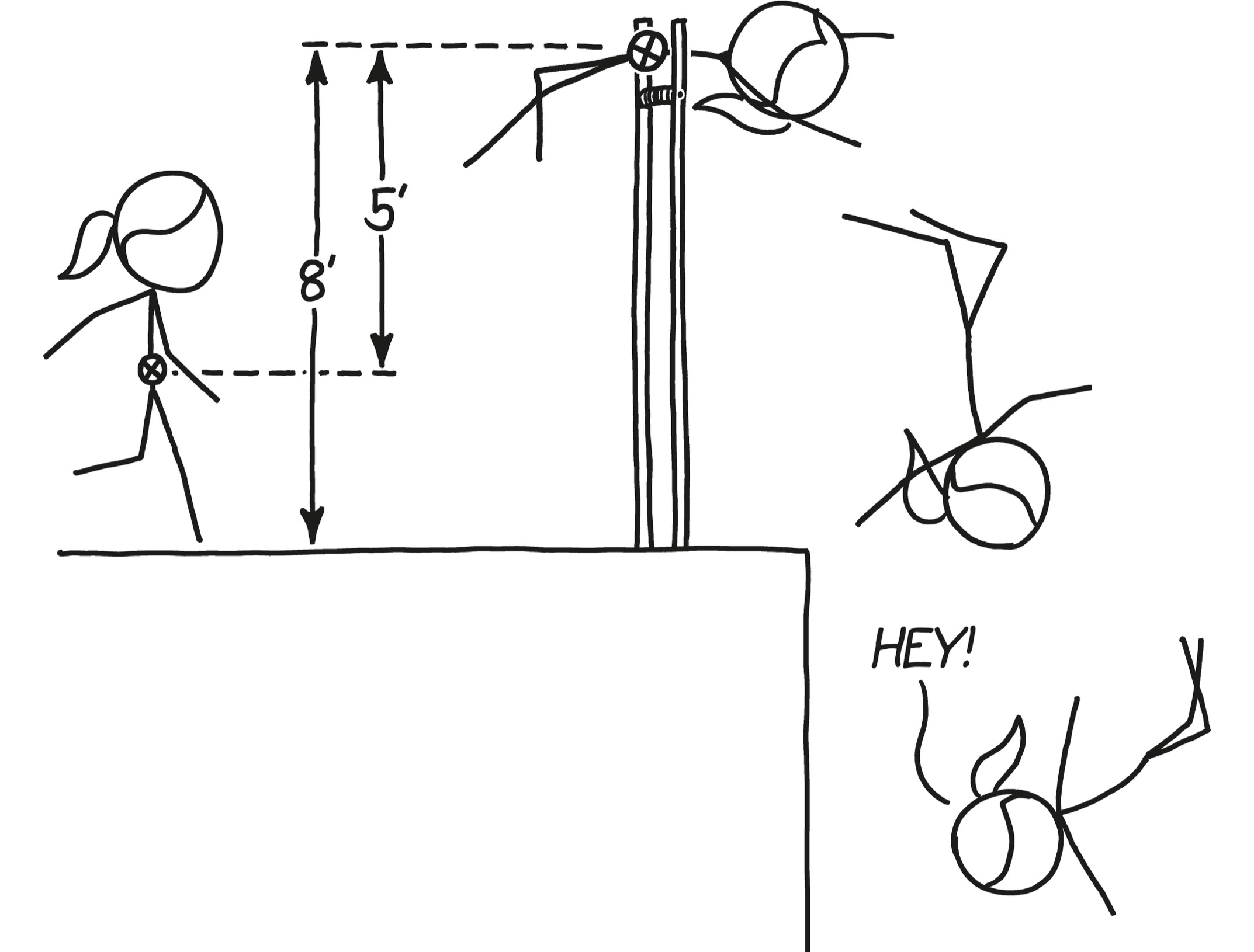

Using a running start can help. This is what athletes competing in the high jump do, and the world record height is 8 feet. However, that’s measured from the ground. Since high jumpers tend to be tall, their center of mass starts off several feet off the ground, and because of how they fold their bodies to pass over the bar, their center of mass may actually pass under it. An 8-foot high jump doesn’t involve launching the center of their body anything like the full 8 feet.

If you want to beat a high jumper, you have two options:

Dedicate your life to athletic training, from an early age, until you become the world’s best high jumper.

Cheat.

The first option is no doubt an admirable one, but if that’s your choice, then you’re reading the wrong book. Let’s talk about option two.

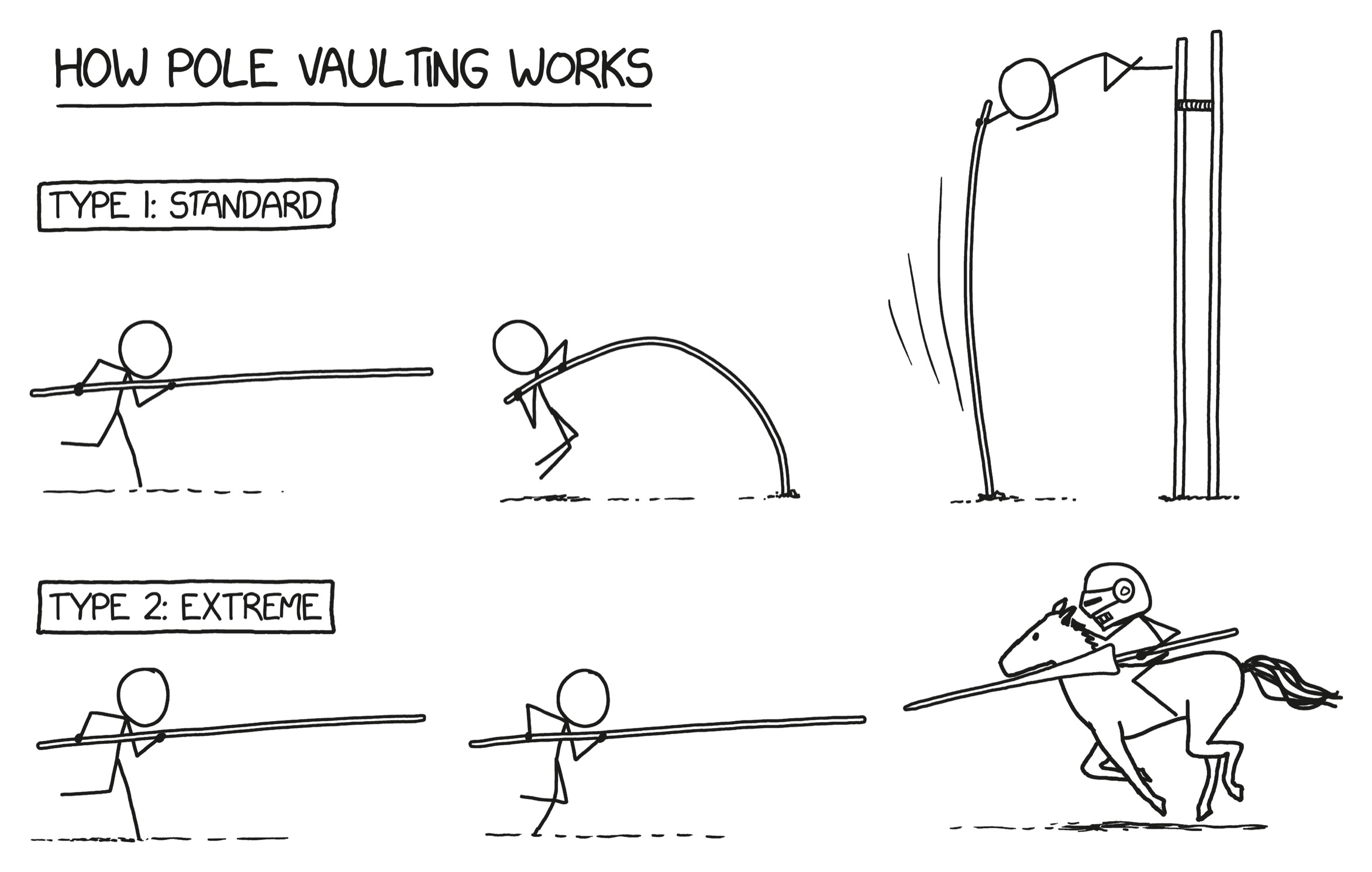

There are a lot of ways you could cheat at high jump. You could use a ladder to get over the bar, but that’s hardly jumping . You could try wearing those spring-loaded stilts * popular with extreme sports enthusiasts, which—if you’re athletic enough—might be enough to give you the edge over an unassisted high jumper. But for sheer vertical height, athletes have already come up with a better technique: pole vaulting.

In pole vaulting, athletes start running, stick a flexible pole into the ground in front of them, and launch themselves into the air. Pole vaulters can fling themselves several times higher than the best unassisted high jumpers.

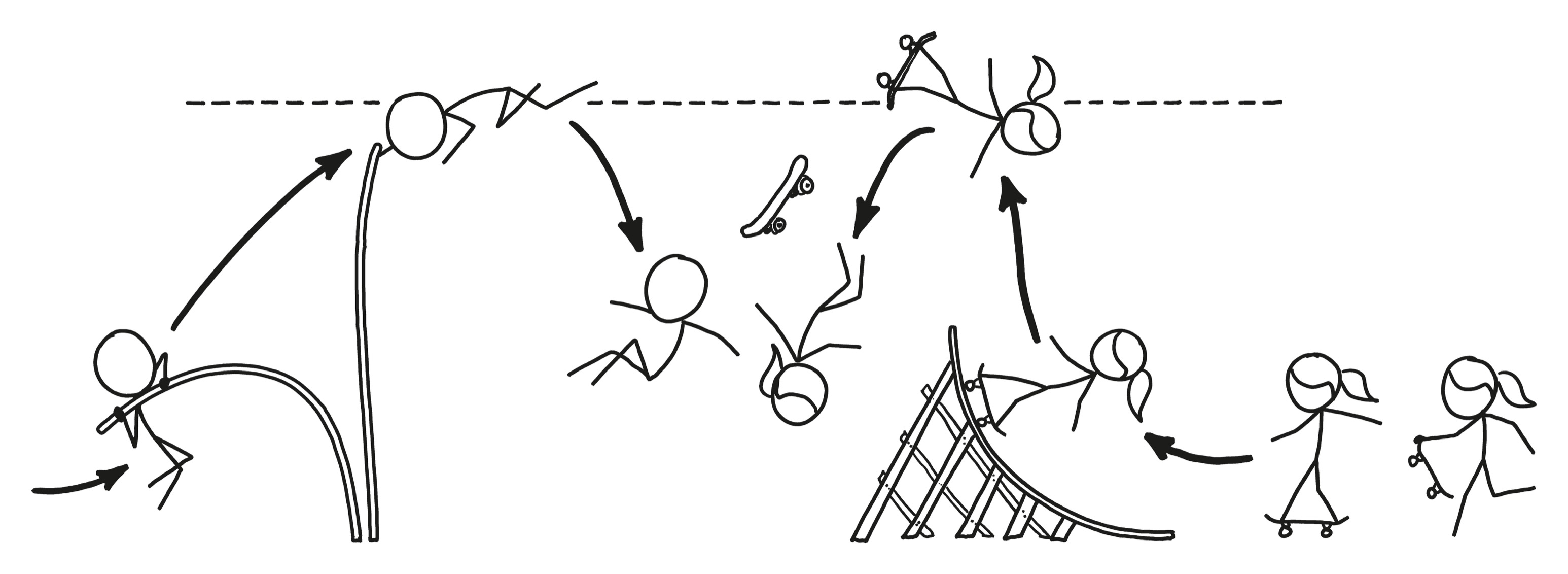

The physics of pole vaulting are interesting, and don’t revolve around the pole nearly as much as you might think. The key to vaulting isn’t the springiness of the pole, it’s the athlete’s running speed. The pole is just an efficient way to redirect that speed upward. In theory, the vaulter could use some other method to change direction from forward to up . Instead of sticking a pole in the ground, they could jump onto a skateboard, go up a smooth curved ramp, and reach just about exactly the same height as the vaulter.

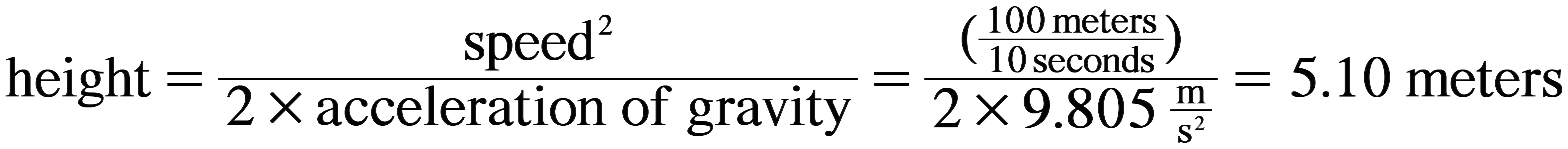

We can estimate a pole vaulter’s maximum height using simple physics. A champion sprinter can run 100 meters in 10 seconds. If an object is launched upward at that speed under Earth’s gravity, a little math can tell us how high it should go:

Since the pole vaulter is running before they jump, their center of gravity starts off above the ground already, which adds to the final height it reaches. A normal adult’s center of gravity is somewhere in their abdomen, usually at a height of about 55 percent of their actual height. Renaud Lavillenie, the world record holder in the men’s pole vault, is 1.77 meters tall, so his center of gravity adds another 0.97 meters or so, giving a final predicted height of 6.08 meters.

How does our prediction compare to reality? Well, the actual world record height is 6.16 meters. That’s pretty close for a quick approximation! *

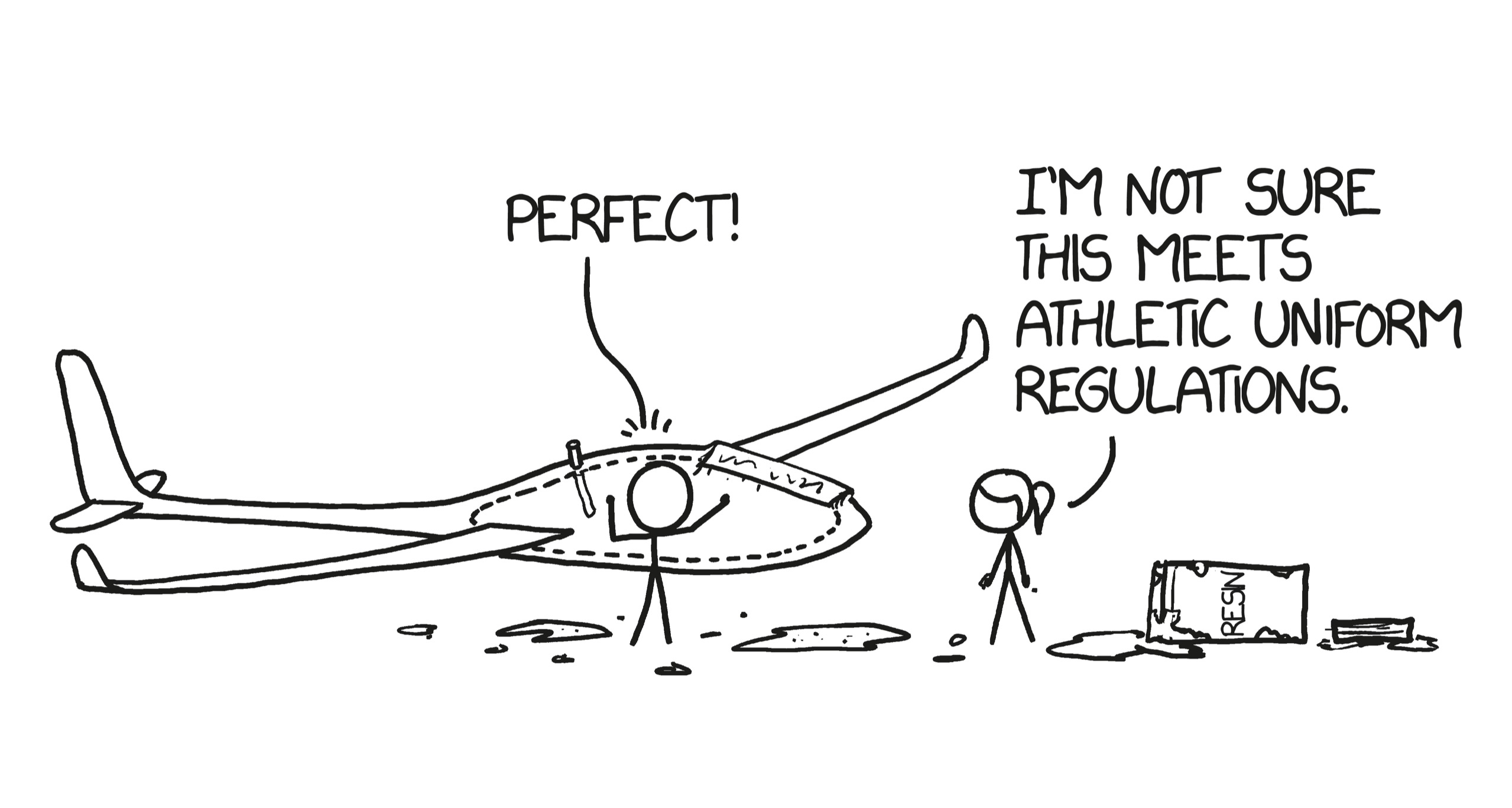

Of course, if you show up at a high jump championship with a vaulting pole, you’ll be immediately disqualified. * But while the judges might object, they probably won’t stop you, especially if you wave the pole around threateningly as you approach.

Your record won’t go on the books, but that’s ok—you’ll know in your heart how high you jumped.

But if you’re willing to cheat more blatantly, you can go higher than 6 meters. A lot higher. You just need to find the right spot to launch from.

Runners take advantage of aerodynamics. They wear sleek, tight-fitting outfits to cut down on air resistance, which helps them to gain greater speeds and thus soar higher. * Why not take it a step further?

Of course, actually pushing yourself forward with a propeller or a rocket doesn’t count. There’s no way you can call that a “jump” with a straight face. * That’s not a jump, that’s a flight . But there’s nothing wrong with just ... gliding a little.

The path of every falling object is affected by how the air moves around it. Ski jumpers adjust their shape to gain a huge aerodynamic boost to their jumps. In an area with the right winds, you can do the same thing.

When sprinters run with the wind at their backs, they can reach higher speeds. Similarly, if you jump in an area where the wind is blowing upward , you can reach greater heights.

It takes strong wind to push you upward—wind blowing faster than your terminal velocity . Your terminal velocity is the maximum speed you’ll reach while falling through air, when the force of the air rushing past balances out the downward acceleration of gravity. This is the same as the minimum upward wind speed needed to lift you off the ground. Since all motion is relative, it doesn’t really matter whether you’re falling downward through the air or the air is blowing upward past you. *

People are a lot denser than air, so our terminal velocity is pretty high. A falling person’s terminal velocity is around 130 miles per hour (mph). In order to get much of a boost from wind, you’ll need the upward wind speed to be at least in the same range as your terminal velocity. If the wind is a lot slower, then it won’t affect your jump height very much.

Birds use columns of warm, rising air—called thermals—like elevators. The birds soar in circles without flapping, letting the rising air carry them upward. These thermal updrafts are relatively weak; to lift your larger human body, you’ll need to find a stronger source of rising air.

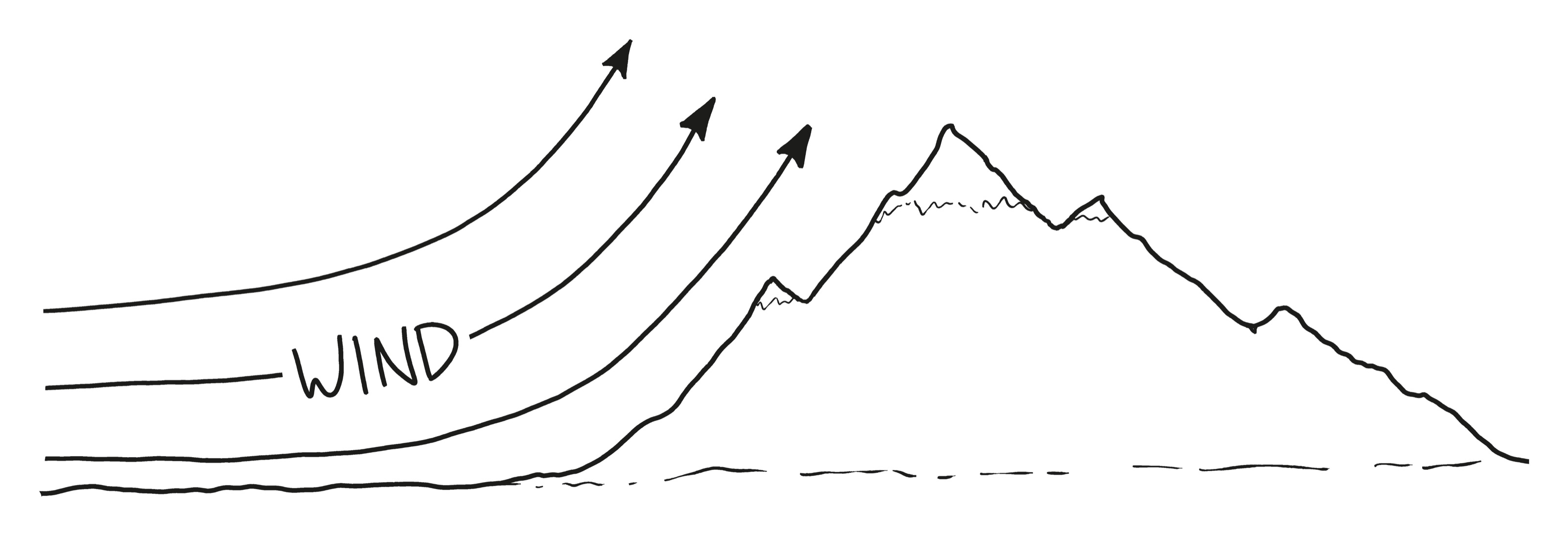

Some of the strongest updrafts near the ground happen near mountain ridges. When wind encounters a mountain or ridge, the airflow can be diverted upward. In some areas, these winds can be quite fast.

Unfortunately, even at the best spots, the vertical winds generally aren’t even close to a human’s terminal velocity. At best, you’d only gain a little bit of height from the wind’s assist. *

Instead of trying to increase the wind speed, you can try reducing your terminal velocity with aerodynamic clothing. A good wingsuit—clothing with sheets of material between the arms and legs—can reduce a person’s sink rate from 130 mph to as little as 30 mph. That’s still not enough to actually ride winds upward, but it would add some height to your jump. On the other hand, you’d have to do your running approach in a full wingsuit, which would probably cancel out the benefit from the wind.

To add substantial height to your jump, you need to go beyond wingsuits, into the world of parachutes and paragliders. These large contraptions reduce a person’s falling speed enough so that surface winds can easily get strong enough to lift them. Skilled paragliders can launch from the ground and ride ridge winds and thermals to thousands of feet.

But if you want a real high jump record, you can do even better.

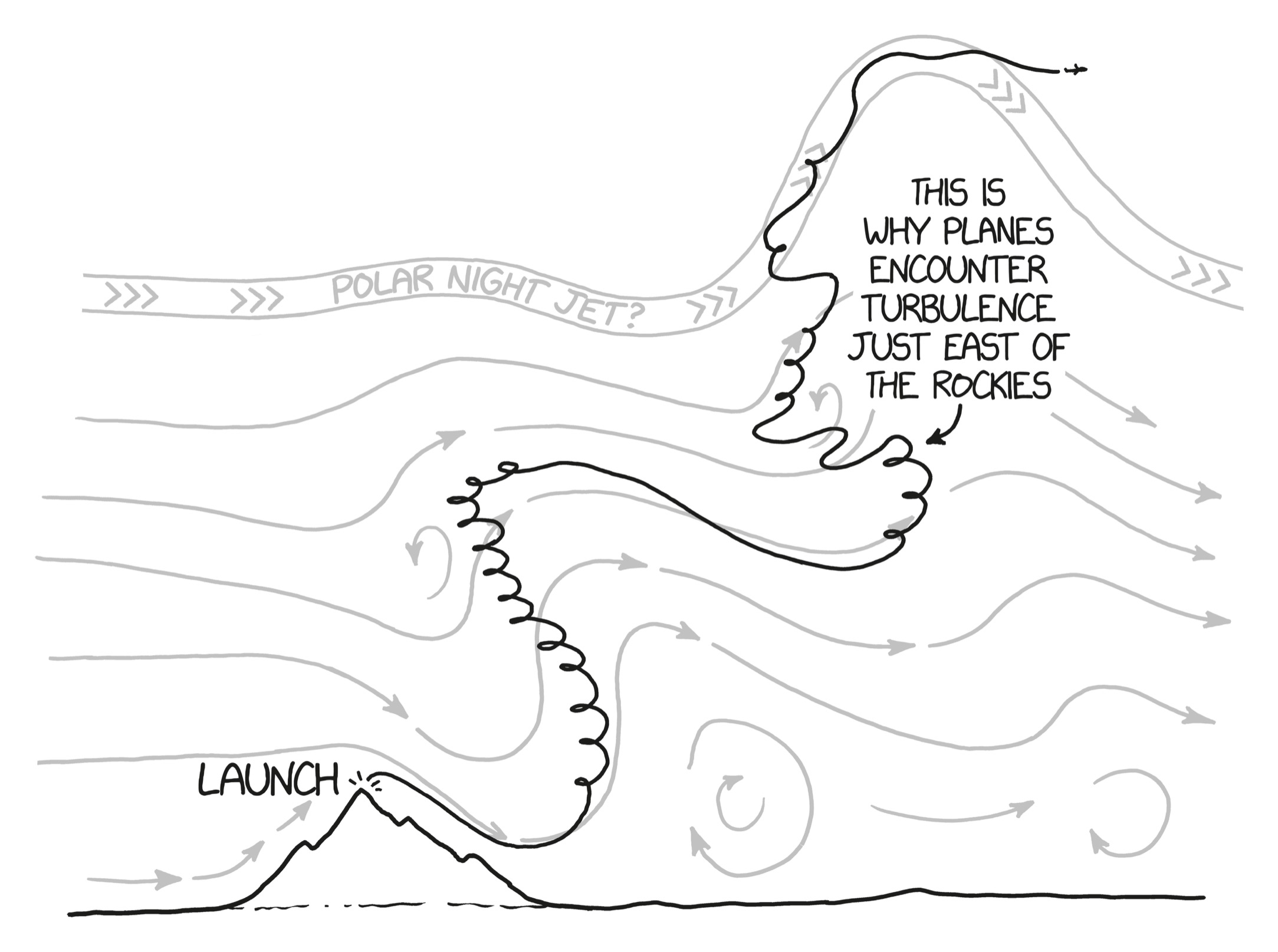

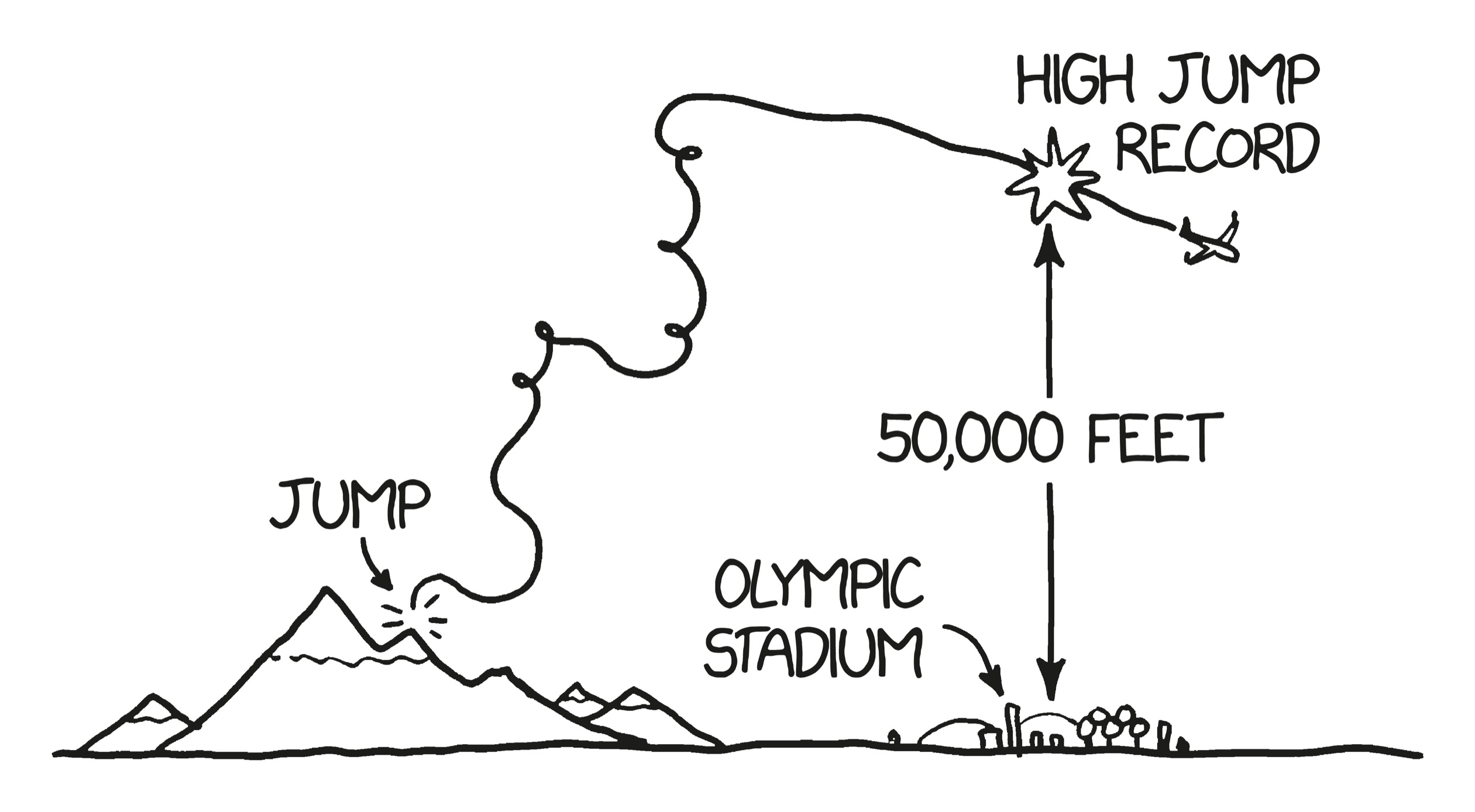

In most areas where air flows over mountains, the “mountain waves” extend up only into the lower atmosphere, which limits the height that gliders can reach. But in some places, when conditions are just right, these disturbances may interact with the polar vortex and polar night jet, * creating waves that reach into the stratosphere.

In 2006, glider pilots Steve Fossett and Einar Enevoldson rode stratospheric mountain waves to over 50,000 feet above sea level. That’s almost twice as high as Mt. Everest, and higher than the highest commercial airline flights. That flight set a new glider altitude record. Fossett and Enevoldson say they could have ridden the stratospheric waves even higher—they only turned back because the low air pressure caused their pressure suits to inflate so much that they couldn’t operate the controls.

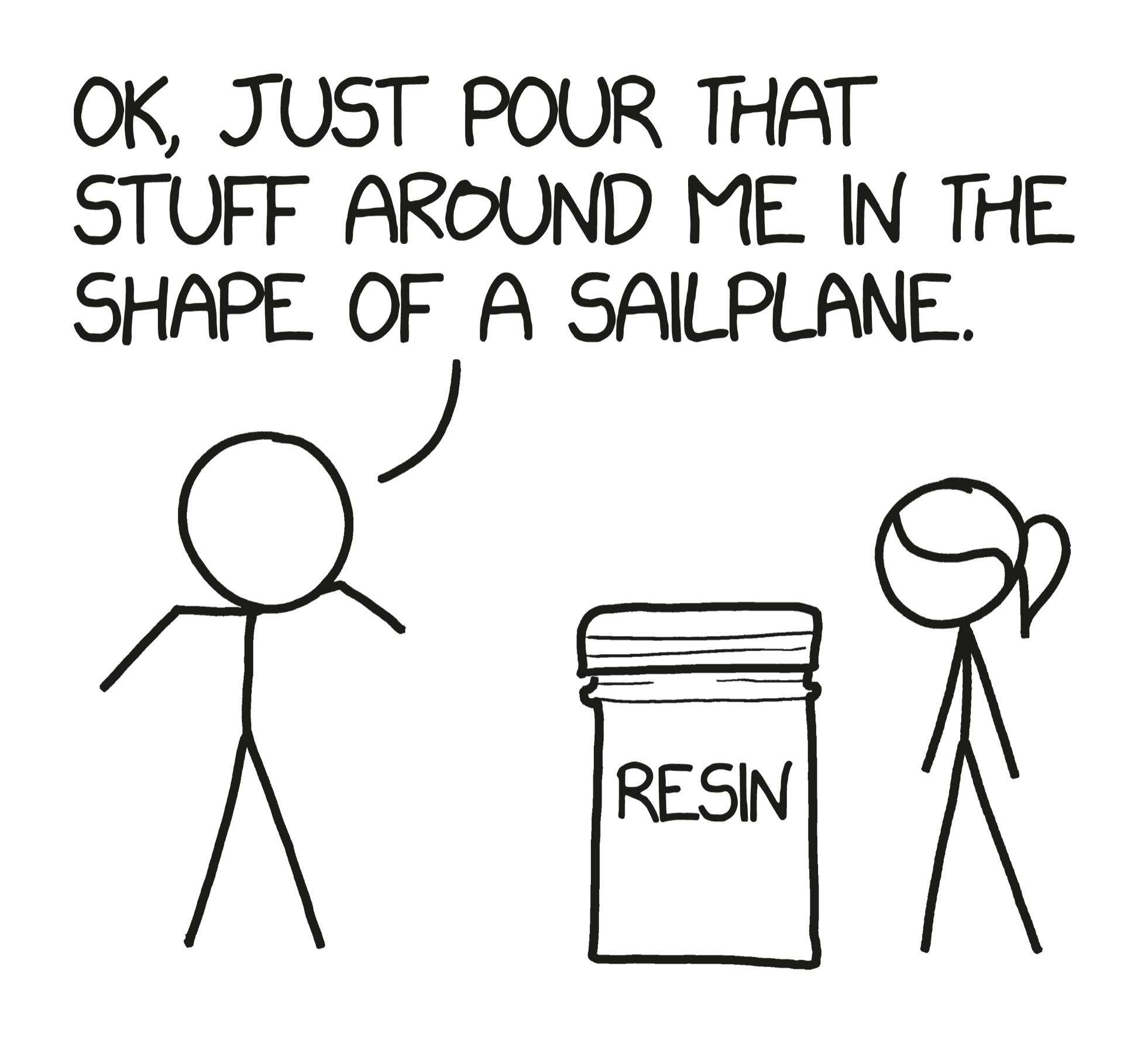

If you want to jump high, you just need to construct an outfit shaped like a sailplane—you can make one out of fiberglass resin and carbon fiber—and head to the mountains of Argentina.

If you find the right spot, and if conditions are just right, you can seal yourself into your sailplane suit, * jump into the air, catch the ridge lift, and ride the wind into the stratosphere. It’s possible that a glider pilot riding these waves might be able to cruise at higher altitudes than any other wing-borne aircraft. That’s not bad for a single jump! *

If you’re really lucky, maybe you can find a spot that’s upwind from where the Olympics are being held. That way, when you jump off the edge, the winds in the stratosphere will carry you over the venue ...

... letting you set the greatest high jump record in the history of the sport.

They probably won’t give you a medal, but that’s fine. You’ll know you’re the real champion.