On Estimating Functional Gene Number in Eukaryotes

On Estimating Functional Gene Number in Eukaryotes

S. J. O’Brien

Editor’s Note

Around 30 years before the Human Genome Project mapped the tens of thousands of protein-coding genes of the human genome, debate over the eukaryotic gene complement was rife. The total number of genes was thought to be far less than the amount of DNA in the haploid genome, leading some to suggest that over 90% of the eukaryotic genome was nonfunctional or “junk”. Here geneticist Stephen J. O’Brien questions this assumption, arguing that the evidence for junk DNA is based on the response of the functioning genes to natural selection. Non-coding DNA is now thought to comprise most of the human genome, but the term “junk” is used with caution since functions have been ascribed to some so-called “junk” sequences. 中文

MANY recent studies have been concerned with the construction of biological model systems to describe adequately regulation of gene action during development of eukaryotes 1-5 . The number of genes in mammals and Drosophila has been suggested to be 1 to 2 orders of magnitude less than the amount of available DNA per haploid genome could provide 2-7 . Although Drosophila and mammalian nuclei contain enough unique DNA to specify for respectively 10 5 and 10 6 genes of 1,000 nucleotide pairs 8,9 , it has been argued that a much lower estimate of functional gene number is more reasonable 2-7 . Conversely, these conclusions indicate that more than 90% of the eukaryotic genome may be composed of nonfunctional or noninformational “junk” DNA. Here we demonstrate these estimations have not been fundamentally proven; rather they are based on simplifying assumptions of questionable validity, in some cases contradictory to experimental data. 中文

The perceptive model proposed by Crick 5 provides that the structural genes for proteins are situated generally in the interbands observed in the giant salivary gland chromosomes of Drosophila . The chromosome bands, which contain all but a few % of the DNA, are the sites of regulatory elements and presumably large amounts of noninformational DNA. The model thus predicts approximately 5,000 structural genes in Drosophila , the approximate number of salivary gland bands which can be observed. 中文

This model is strongly supported by the elegant work of Judd et al . 10 who examined 121 lethal and gross morphological point mutations that map in the zeste to white region of the tip of the X chromosomes in D . melanogaster . There are 16 salivary gland chromosome bands or chromomeres in this region corresponding to 16 complementation groups of the morphological or lethal point mutations. In addition a series of overlapping deficiencies supports the 1 band:1 complementation group relationship. Extrapolation over the entire genome gives approximately 5,000 complementation groups or genes to 5,000 chromosome bands. There are also estimates available on the total number of lethal loci in the Drosophila genome. By screening for large numbers of lethal chromosomes either in natural populations or following irradiation, it is possible to relate the frequency of allelism to the number of lethal loci by a simple Poisson distribution: and the number of lethals thus measured in Drosophila gives a result between 1,000-2,000 11,12 . 中文

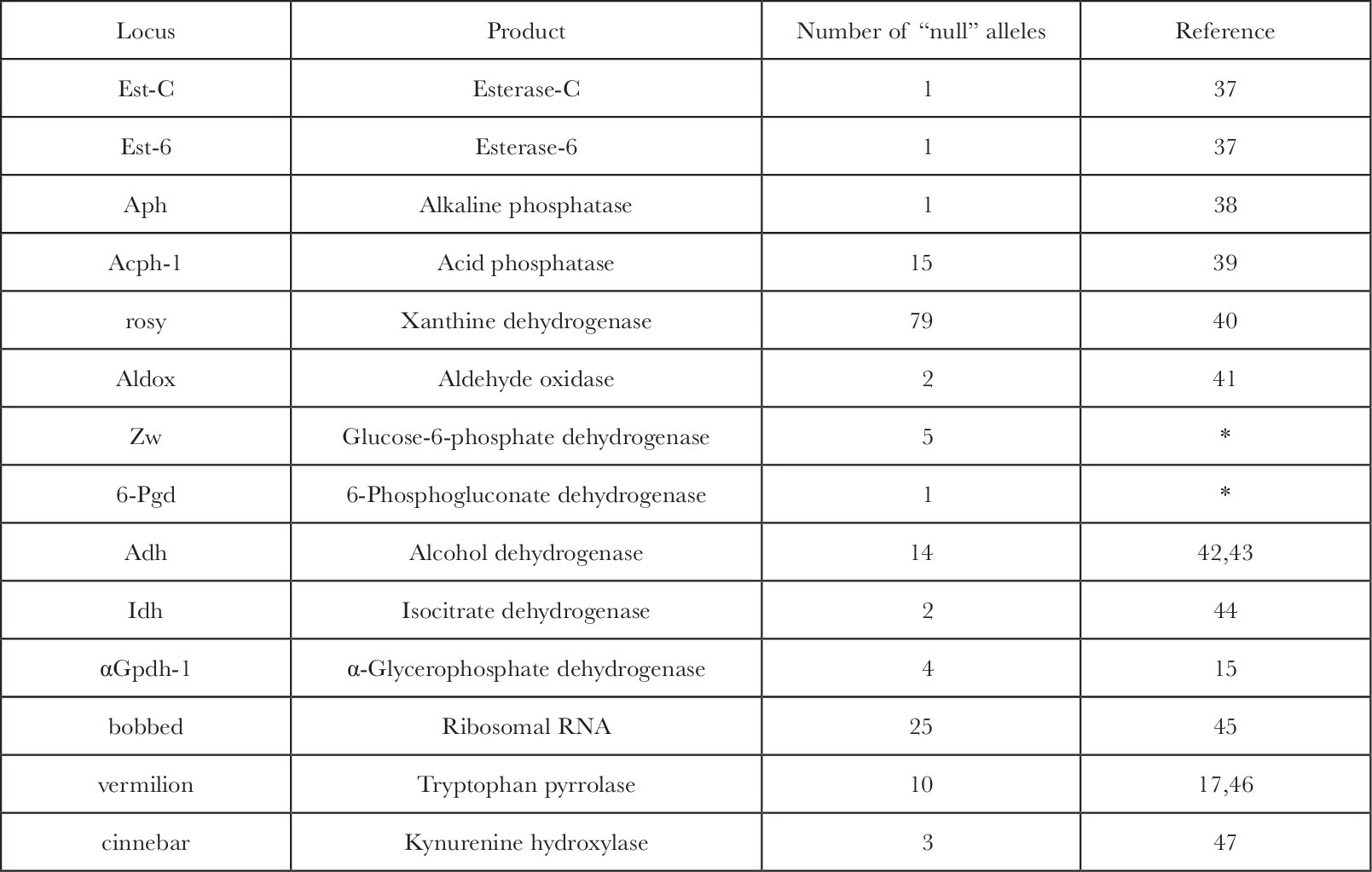

The problem with extrapolation of the fine structure analysis and the lethal data to the functional gene number is our inability to answer the question: how many genes when mutated are capable of producing a lethal or gross morphological phenotype? The answer is not known specifically but the available data suggest that only a very small percentage of all gene products are critical enough to kill the organism if absent. In Drosophila over 30 genes have a known gene product 13 , of which there are 14 at which “null” alleles eliminate the protein, its activity, or the RNA product entirely, and of these (Table 1) only the bobbed locus has lethal alleles 14 . Most alleles, however, at that locus, which is the structural gene for ribosomal RNA, are viable even at very low levels of rRNA. The other genes, which code for enzymes whose function a priori seemed essential for normal metabolism, are in no case lethal when homozygous for completely “null” alleles. 中文

Table 1. Genes in Drosophila melanogaster with Known Gene Products and Recovered “Null” Alleles

* W. J. Young, personal communication.

Null alleles at the first eleven loci above were detected by the loss of histochemical stain development on an electrophoretic gel. The sensitivity of this assay detects at least 5% of normal enzyme levels. In several cases ( Acph-1, rosy, Adh, α Gpdh-1 ), analytical enzyme assays with a sensitivity near 0.1% of wild type enzyme levels also failed to detect trace activity in “null” homozygotes. In the two cases where cross reacting material (CRM) was measured ( Acph-1 and ry ) it was also negligible. 中文

Null alleles of at least two of the loci were induced in a crossing scheme that would have recovered lethal alleles ( α Gpdh-1 and Acph-1 ). A lethal “null” allele would also be detected as an exceptional heterozygote with normal alleles of different eletrophoretic mobilities in those cases of “null” alleles discovered in natural or laboratory populations ( Est-C, Est-6, Aph, Aldox, and Idh ). 中文

Five of the fourteen loci have alleles which produce visible recessive phenotypes; ry , cn and v affect eye colour, bb affects bristles, and α Gpdh-1 “null” mutations which, although they appear morphologically normal, lack ability to sustain flight. The fraction 5 of 14 should not, however, be taken as an estimation of the fraction of loci at which “null” alleles produce an observable phenotype. This number is probably an overestimate because 4 of the 5 loci in question (all except α Gpdh-1 ) were discovered initially as morphological mutations and their gene product was deduced and identified from their visible phenotype. 中文

The eye colour mutations affect enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of eye pigments, and the bobbed locus, which shows a syndrome of effects usually associated with protein synthesis, was identified as the gene for rRNA. The phenotype of the α Gpdh-1 “null” mutations might easily have been missed had not the importance of the enzyme in insect flight been known previously 15 . The 11 other loci were identified only as the genes for selected enzymes, and of these none exhibited lethality or any morphological phenotype when “null” alleles were found. 中文

In two cases double “null” mutants of alkaline and acid phosphatase (R. S. MacIntyre, personal communication) and of Z w and 6-Pgd (W. J. Young, personal communication) were constructed and proved viable, fertile, and morphologically normal. Also, in two of the five cases where there is an observable phenotype, bb and α Gpdh-1 , there occurs a modification of the phenotype in the afflicted stocks. In the case of bb the diminished rDNA cistrons become “magnified” to approach the wild type rRNA levels within a few generations 16 . Flies genetically deficient for α-glycerophosphate dehydrogenase lack the ability to sustain flight due to their disrupted α-glycerophosphate cycle 15 , but after 25 generations this phenotype becomes modified and flies recover the ability to fly normally (S. O’Brien, unpublished data). Biological adaptive capacity for physiological compensation for lesions in the structural genes of important functions must be very extensive to protect the fly so efficiently from genetically sensitive loci even in the presumably critical functions. 中文

One might argue that even the smallest cytologically observable mutations in most cases are recessive lethals 10,14,17 . Resolution of such cytology, however, demands that at least 1 of the 5,000 chromomeres of Drosophila polytene chromosomes must be absent to detect a deletion. The precision of the technique then is at the level of 10 6 nucleotides, the average amount per chromomere, enough DNA for 20 genes of average length. I suggest that there could be up to 20 functional genes in each region of which only one might be lethal in its mutant configuration. 中文

A second widely used argument which suggests a minimum of informational DNA in the eukaryote genome (less than 10% of the available DNA) states that the mutational genetic load would be inordinate if mammals used all their DNA to carry and transmit biological information. Ohno 4 states that with a mutation rate of 10 -5 in mammals containing enough DNA for 3×10 6 genes, if all this DNA were informative, each gamete would contain 30 new mutations, which would produce a genetic load sufficient to have exterminated mammals years ago. Evaluation of these mutational and substitutional load restrictions on functional gene number depends upon the unresolved question of the selective neutrality of gene substitutions, and will be treated from both perspectives. 中文

If one accepts that the majority of gene substitutions and polymorphisms are selectively neutral, then the restrictions imposed by a genetic load on functional gene number become negligible. Neutral gene substitutions certainly cannot contribute to any accumulating substitutional or mutational load which depends upon selective disadvantage for its action. We must therefore estimate whether the number of functional genes are minimal, or rather that most gene substitutions are inconsequential with respect to natural selection. Proponents of selective neutrality feel that most substitutions are neutral, which removes any restrictions on large numbers of functional gene loci. 中文

There have been serious objections raised concerning the role of selective neutrality 18,19 . One of the weakest tenets of this hypothesis is that it is based very heavily on the multiplicative aspect of fitness, which assumes that selection acts independently and in an additive fashion over all loci in a population. That this is not the case has been argued cogently by several authors 20-22 . The main point is that selection acts on the whole organism, not on the genotype at each polymorphic locus in each organism in a population 22 . If multiplicative fitness is an unrealistic assumption, then besides questioning selective neutrality as a major force, it also removes the restrictions imposed by the mutational and substitutional load on the number of functional genes. 中文

There are a number of ways, suggested by myself and others, that a population can escape the rigours of multiplicative fitness, or more specifically, immediate selective consequence. These include diploidy 23 , epistasis 20,21 , synonymous base substitutions 7 , frequency dependent selection 24 , linkage disequilibrium 25 , and alternative metabolic pathways (Table 1). All these factors, because they can effectively shield new mutations from the rigours of natural selection, even though the mutations may be deleterious in another genetic environment, counter the assumption of multiplicative fitness. If this assumption is removed, so also is the necessity of restrictive genome size in Drosophila and mammals. 中文

Long sequences (150-300 nucleotides) of polyadenylic acid are generally attached to messenger RNA in eukaryote cells 26-28 . Although post-transcriptional addition of poly A to messenger RNA has been postulated 29-31 , the presence of poly T of comparable length in the nuclear DNA suggests transcriptional addition also 32 . RNA-DNA hybridization kinetics show that up to 0.55% of mammalian nuclear DNA anneals with poly A, corresponding to 1.1% poly dA-dT sequences 32 . This suggests a minimum of 5×10 4 poly dA-dT sites. If each of these sequences is transcribed with an adjacent structural gene, the number of functional genes must be greater than 5×10 4 by the addition of post-transcriptionally added poly A messages, plus non-messenger RNA genes, plus all non-transcribed regulatory genes. This number may be considerable. 中文

In the cellular slime mould, Dictyostelium discoideum , 28% of the nonrepetitive nuclear genome is represented in the cellular RNA during the 26 h developmental cycle 33 . If only one of the complementary strands of DNA of any gene is transcribed, the estimate represents 56% of the single copy DNA. Because the nonrepetitive genome size of Dictyostelium contains approximately 3×10 7 nucleotide pairs 34 , there are at least 16,000 to 17,000 RNA transcripts of average gene size (1,000 nucleotides) present over the cell cycle. Similarly, 10% of the mouse single copy sequences are represented in the cellular RNA of brain tissue. This hybridization result implies that a minimum of 300,000 different sequences of 1,000 nucleotides each are present in the mouse brain alone 35 . Results of RNA-DNA annealing experiments with Drosophila larval RNA indicate that between 15-20% of the unique nuclear genome is represented in larval RNA (R. Logan, personal communication), which corresponds to 30,000-40,000 RNA gene transcripts of average length. As the mouse and Drosophila data include only certain tissues and developmental times respectively, they probably are underestimates of the total unique DNA transcribed by 10-30%, based upon the degree of differences in RNA sequences exhibited at various developmental stages in Dictyostelium . 中文

Interpretation of DNA-RNA hybridization experiments as an estimation of functional genes could be argued to be invalid because a large proportion of cellular RNA is the rapidly degraded “heterogeneous nuclear RNA” which never leaves the nucleus for translation 26,28,36 . RNA does not have to be translated to have a function, indeed RNA has a number of functions other than translation. Three points support gene function of such RNA when considered together: first, the actual presence of the gene; second, the transcription of information, and third, the transcription of different non-repetitive sequences at different developmental times and in different tissues 33,35 . 中文

The major arguments supporting the contention that much of eukaryotic DNA is neither transcribed nor functional are based essentially on the response of the functioning genes to natural selection. The tremendous amounts of physiological and/or genetic compensatory mechanisms which defer the presumed deleterious effects of mutations make such arguments subject to re-evaluation. Furthermore, the molecular data with the poly A sites and RNA transcript estimates suggest greater amounts of gene action than have been presumed. 中文

Although it is impossible to measure exactly the number of functional genes in eukaryotes, the acceptance of evidence for these minimum amounts seems a little premature. 中文

Supported by a postdoctoral award from the National Institute of General Medical Science. 中文

I thank Drs. R. J. MacIntyre, W. Sofer, R. C. Getham, J. Bell, and M. Mitchell for criticism and discussion. 中文

( 242 , 52-54; 1973)

S. J. O’Brien

Gerontology Research Center, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore City Hospitals, Baltimore, Maryland 21224

Received August 28; revised December 11, 1972.

References: