Irregularity is called so in contrast with regularity. If all linguistic forms are regular morphologically and phonologically, there are by no means irregulars by the name. But it is not otherwise true that all linguistic forms are irregular. Irregularity does not exist in every grammatical category. In modern English, irregularity lies in three grammatical fields: irregular markings of plural nouns, past-tense and past-participle verbs, and comparatives and superlatives of adjectives and adverbs, among which they are all in the minority.

The majority of English countable nouns are regular and predictable in the spelling of the plural form by adding -s to the end of the singular form or -es to those singulars that end in a sibilant sound(/s/, /z/, /ts/, /dz/). However, there are several nouns which are irregular in their spelling. These nouns are exceptions when it comes to making them plural. When irregular nouns become plural, their spellings change in different ways or they may not change at all from singular forms. Some nouns that end in -f or -fe are changed to -ves in the plural, as in calf-calves, half-halves . Some nouns change the vowel sound in becoming plural as in foot-feet, goose-geese, louse-lice, man-men, mouse-mice, tooth-teeth, woman-women . Some Old English plurals are still in use, as in child-children, ox-oxen . Some nouns ending in -o take -s as the plural, while others take -es: auto-autos, echo-echoes . Some nouns do not change at all: deer-deer, offspring-offspring . Some nouns retain foreign plurals: criterion-criteria . Other irregular plurals retain from different languages: tempo-tempi (Italian), schema-schemata (Greek). More can be found in Appendix I.

The English language has a large number of irregular verbs. In the great majority of these, the past participle and/or past tense is not formed according to the usual patterns of English regular verbs. Other parts of the verb—such as the present 3rd person singular -s or -es, and present participle -ing—may still be formed regularly.

Among the exceptions are the verb to be and certain defective verbs, which cannot be conjugated into certain tenses.

Most English irregular verbs are native, originating in Old English(an exception being “catch” from Old North French “cachier”). They also tend to be the most commonly used verbs. The ten most commonly used verbs in English are all irregular.

In general, English contains about 180 “irregular” verbs that form their past tense in idiosyncratic ways, such as ring-rang , sing-sang , go-went , and think-thought . In contrast with the regulars, the irregulars are unpredictable. The past tense of sink is sank , but the past tense of slink is not slank but slunk ; the past tense of think is neither thank nor thunk but thought , and the past tense of blink is neither blank nor blunk nor blought but regular blinked . Also in contrast to the regulars, “irregular verbs define a closed class: there are about 180 of them in present-day English, and there have been no recent new ones”(Pinker, 1999: 5). And they have a corresponding advantage compared with the regulars: there are no phonologically unwieldy forms such as edited ; all irregulars are monosyllables(or prefixed monosyllables such as become and overtake )that follow that canonical sound pattern for simple English words. For instance, the past tense of T-forms include: burnt , clapt , crept , dealt , dreamt , dwelt , felt , leant , leapt , learnt , meant , spelt , smelt , spilt , spoilt , stript , vext . T-forms can be divided into two categories: those with a vowel change and those without a vowel change. T-forms with a vowel change include: crept , dealt , dreamt , felt , leapt , meant . The T-forms with a vowel change are still very common in modern English. In fact, crept , dealt , felt and meant are the only accepted forms. In the case of dreamt and leapt , although dreamt and leapt are still quite common and acceptable in both written and spoken English, the regular forms dreamed and leaped seem to be more popular in modern usage. T-forms without a vowel change include: burnt , clapt , dwelt , leant , learnt , spelt , smelt , spilt , spoilt , stript , vext . The T-forms without a vowel change are slowly disappearing from the language. Dwelt is the only form in this category which is more frequently used than the regular -ed form. Burnt , leant and learnt are still relatively common in spoken English and fairly common in written English. Spelt , smelt , spilt and spoilt are quickly disappearing. Stript , clapt and vext are rarely used in contemporary English.

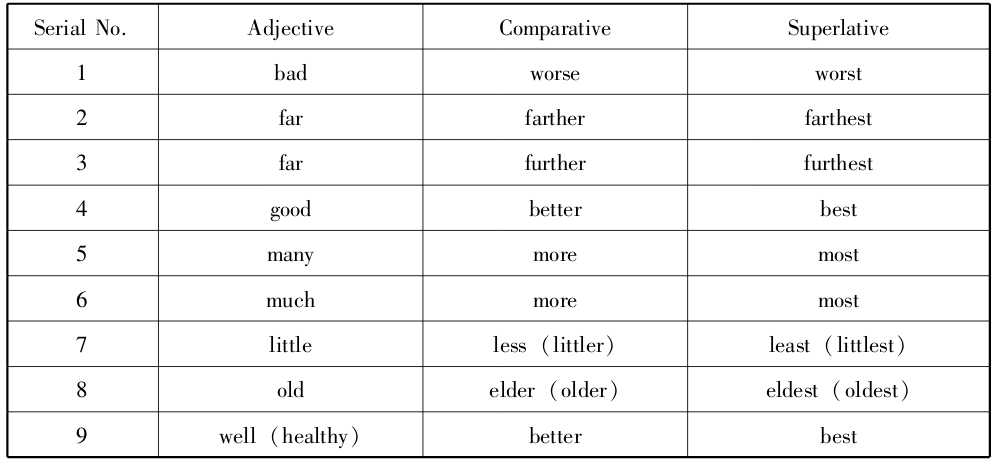

The regular way to make comparative or superlative adjectives is to add -er or -est to the end of bare adjectives or adverbs, or to use the peripheral form of more or most before. A small number of adjectives, however, are irregular and some of these can be regular or irregular. The most important ones are listed in Table 1.1:

Table 1.1 Irregular comparatives and superlatives of adjectives and adverbs