From topics.nytimes.com 译/ 辛献云

音频

作为视觉艺术家,宫崎骏既是一位恣意豪放的幻想家,又是一位严谨的自然主义者;作为故事讲述者,他所讲述的寓言故事既让人耳目一新,又给人一种说不出的古老感。他作品的奇妙感既来自于他给拥挤的青少年奇幻作品市场带来的那份新鲜和新奇感,又来自一种令人紧张的神秘离奇的熟悉感,仿佛他将深埋在集体无意识中的传说复活了。

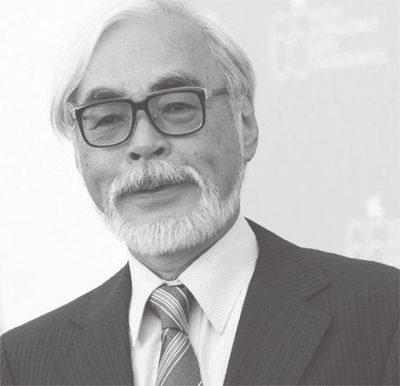

Hayao Miyazaki is regarded by many people as the world's greatest maker of animated films. At the age of 71, with more than 20

features

to his credit, Mr. Miyazaki has become a beacon for those who believe that animation has a special power to tell stories with universal appeal. "He celebrates the quiet moments," said John Lasseter, the chief creative officer of Pixar and Disney Animation Studios, in

enumerating

to his credit, Mr. Miyazaki has become a beacon for those who believe that animation has a special power to tell stories with universal appeal. "He celebrates the quiet moments," said John Lasseter, the chief creative officer of Pixar and Disney Animation Studios, in

enumerating

traits that make Mr. Miyazaki "one of the most original" filmmakers ever.

traits that make Mr. Miyazaki "one of the most original" filmmakers ever.

Mr. Miyazaki's work has often combined computer animation with traditional techniques and has provided inspiration for films like the Toy Story

installments

, Cars and Up.

, Cars and Up.

Mr. Miyazaki roots are in both

manga

and

anime

and

anime

(comic books and animated films). Starting with his 1997 epic, Princess Mononoke, he has used computer-generated imagery in his movies.

(comic books and animated films). Starting with his 1997 epic, Princess Mononoke, he has used computer-generated imagery in his movies.

The conscious sense of mystery is the core of Mr. Miyazaki's art. Spend enough time in his world and you may find your perception of your own world refreshed, as it might be by a similarly intensive immersion in the

oeuvre

of

Ansel Adams

of

Ansel Adams

,

J. M. W. Turner

,

J. M. W. Turner

or

Monet

or

Monet

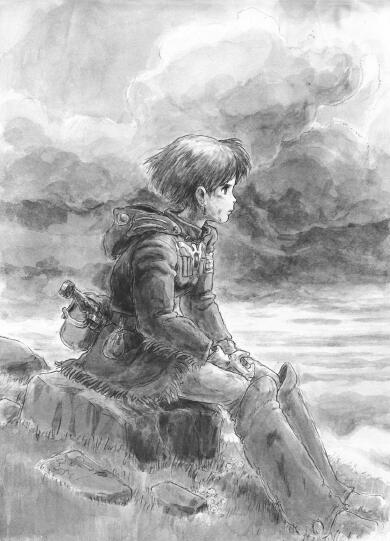

. After a while, certain vistas—a rolling meadow dappled with flowers and shadowed by high cumulus clouds, a range of rocky foothills rising toward snow-capped peaks, the fading light at the edge of a forest—deserve to be called Miyazakian.

. After a while, certain vistas—a rolling meadow dappled with flowers and shadowed by high cumulus clouds, a range of rocky foothills rising toward snow-capped peaks, the fading light at the edge of a forest—deserve to be called Miyazakian.

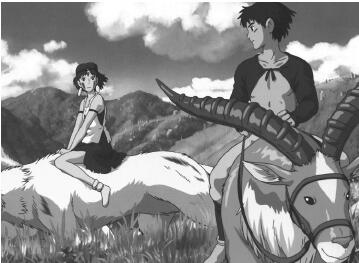

So do certain stories, especially those involving a resourceful, serious girl contending with the machinations of wise old women and the sufferings of enigmatic young men. And so do certain themes: the catastrophic irrationality of war and other violence; the folly of disrespecting nature; the moral complications that arise from ordinary acts of selfishness, vanity and even kindness.

As a visual artist, Mr. Miyazaki is both an

extravagant

fantasist and an exacting naturalist; as a storyteller, he is an inventor of fables that seem at once utterly new and almost unspeakably ancient. Their strangeness comes equally from the freshness and novelty he brings to the crowded marketplace of

juvenile

fantasist and an exacting naturalist; as a storyteller, he is an inventor of fables that seem at once utterly new and almost unspeakably ancient. Their strangeness comes equally from the freshness and novelty he brings to the crowded marketplace of

juvenile

fantasy and from an unnerving, uncanny sense of familiarity, as if he were

resurrecting

fantasy and from an unnerving, uncanny sense of familiarity, as if he were

resurrecting

legends buried deep in the collective unconscious.

legends buried deep in the collective unconscious.

Mr. Miyazaki's world is full of fantastical creatures—cute and fuzzy, icky and creepy, handsome and noble. There are lovable forest sprites, skittering dust balls, as well as talking cats, pigs and frogs. Howl's Moving Castle, adapted from a novel by

Diana Wynne Jones

, features a

garrulous

, features a

garrulous

flame; Spirited Away had its melancholy, wordless no-face monster; Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, the director's first masterpiece, was nearly overrun by enormous trilobite-shaped insects called Om.

flame; Spirited Away had its melancholy, wordless no-face monster; Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, the director's first masterpiece, was nearly overrun by enormous trilobite-shaped insects called Om.

Some of Mr. Miyazaki's creations seem to have precedents and analogues in folklore, fantasy literature and other cartoons. The

porcine

title character in the 1992 film Porco Rosso, for example, is a dashing Italian pilot from the early days of aviation, and it is just conceivable that he might have a

stuttering

title character in the 1992 film Porco Rosso, for example, is a dashing Italian pilot from the early days of aviation, and it is just conceivable that he might have a

stuttering

cousin somewhere on the

Warner Brothers

cousin somewhere on the

Warner Brothers

lot, looking for a pair of pants to match his blazer. But most members of Mr. Miyazaki's ever-expanding

menagerie

lot, looking for a pair of pants to match his blazer. But most members of Mr. Miyazaki's ever-expanding

menagerie

—including Totoro, the slow-moving,

pot-bellied

—including Totoro, the slow-moving,

pot-bellied

, vaguely

feline

, vaguely

feline

character who has become the logo and

mascot

character who has become the logo and

mascot

of his Studio Ghibli—come entirely from the filmmaker's own prodigious imagination. Mr. Miyazaki was once asked where he thought his work fitted within the expanding universe of children's pop culture. "The truth is I have watched almost none of it," he said with a slightly weary smile. "The only images I watch regularly come from the weather report."

of his Studio Ghibli—come entirely from the filmmaker's own prodigious imagination. Mr. Miyazaki was once asked where he thought his work fitted within the expanding universe of children's pop culture. "The truth is I have watched almost none of it," he said with a slightly weary smile. "The only images I watch regularly come from the weather report."

The director, a compact, white-haired man whose demeanor combines gravity with a certain

impishness

, was not just being

flip

, was not just being

flip

. It is hard to think of another filmmaker who is so passionately interested in weather. Violent storms, gentle breezes and sun-filled skies are vital, active elements, bearers of mood, emotion and meaning. His monsters and animals, who share the screen with more conventionally human-looking animated figures—adolescent girls with wind-tossed hair, short skirts and saucer eyes,

mustachioed

. It is hard to think of another filmmaker who is so passionately interested in weather. Violent storms, gentle breezes and sun-filled skies are vital, active elements, bearers of mood, emotion and meaning. His monsters and animals, who share the screen with more conventionally human-looking animated figures—adolescent girls with wind-tossed hair, short skirts and saucer eyes,

mustachioed

soldiers and wrinkled

crones

soldiers and wrinkled

crones

—are an integral part of Mr. Miyazaki's landscape, but the most striking feature of his films may be the landscapes themselves.

—are an integral part of Mr. Miyazaki's landscape, but the most striking feature of his films may be the landscapes themselves.

The action in his movies takes place far from the

cramped

cities of modern Japan, and also from the futuristic metropolises that provide the dystopian backdrop of so much anime. His characters tend to live in hillside villages or in tidy, old-world towns where half-timbered houses

huddle

cities of modern Japan, and also from the futuristic metropolises that provide the dystopian backdrop of so much anime. His characters tend to live in hillside villages or in tidy, old-world towns where half-timbered houses

huddle

along cobblestone streets. As much as they can, in gliders, on broomsticks and under their own magical powers, these characters take to the sky; the

evocation

along cobblestone streets. As much as they can, in gliders, on broomsticks and under their own magical powers, these characters take to the sky; the

evocation

of flying, for

metaphorical

of flying, for

metaphorical

purposes and for the sheer visual fun of it, is one of Mr. Miyazaki's favorite motifs. But one reason he ventures aloft may be to offer a better view of earth and water, which he renders with cinematic precision and painterly virtuosity.

purposes and for the sheer visual fun of it, is one of Mr. Miyazaki's favorite motifs. But one reason he ventures aloft may be to offer a better view of earth and water, which he renders with cinematic precision and painterly virtuosity.

Even though his frames evoke the careful brushwork and delicate emotions of Japanese landscape painting, Mr. Miyazaki is very much a product of postwar Japan, and he sits at the artistic and commercial pinnacle of his country's

churning

,

eclectic

,

eclectic

visual culture. Though he has concentrated almost entirely on film, his earlier career includes television cartoons and manga. Animation, which arrived in Japan with the American occupying force, has since the war become at once the embodiment of the country's antic modernity and also, in the hands of artists like Mr. Miyazaki, a vehicle for reimagining and preserving its history.

visual culture. Though he has concentrated almost entirely on film, his earlier career includes television cartoons and manga. Animation, which arrived in Japan with the American occupying force, has since the war become at once the embodiment of the country's antic modernity and also, in the hands of artists like Mr. Miyazaki, a vehicle for reimagining and preserving its history.

Mr. Miyazaki's movies, whose settings variously evoke medieval Japan, 19th-century Europe and the antique futures of

Jules Verne

and

H. G. Wells

and

H. G. Wells

, cast a sorrowful, sometimes scolding eye toward the present. The antiwar implications of Howl's Moving Castle are as unmistakable as the ecological warnings in Nausicaä and Princess Mononoke, and in nearly every film, technological

hubris

, cast a sorrowful, sometimes scolding eye toward the present. The antiwar implications of Howl's Moving Castle are as unmistakable as the ecological warnings in Nausicaä and Princess Mononoke, and in nearly every film, technological

hubris

, political ambition and greed are the true roots of evil. His criticism of the modern world, though, seems less

topical

, political ambition and greed are the true roots of evil. His criticism of the modern world, though, seems less

topical

than philosophical; his movies do not represent a point of view, but rather present a way of seeing that is radically

at odds

than philosophical; his movies do not represent a point of view, but rather present a way of seeing that is radically

at odds

with what usually meets the eye.

with what usually meets the eye.

It can hardly be denied that they are marvels of escapist entertainment, but this is in no small part because they offer escape from the noise and aggression that dominate so much other modern entertainment. His power to enchant can seem unlimited—the wizards, witches and sorcerers who bedevil, beguile and befriend his heroes are less his

alter egos

than

his kinfolk

than

his kinfolk

—but it arises from and communicates an equally powerful sense of disenchantment

—but it arises from and communicates an equally powerful sense of disenchantment

It is not that Mr. Miyazaki's films are pessimistic, exactly; being fairy tales, they do arrive at happy endings. ("I'm not going to make movies that tell children, 'You should despair and run away,'" he said.) But the route he chooses toward happiness can be troubling, perhaps especially to an American audience that expects sentimental affirmations based on clear demarcations between good and evil. The division of the world into heroes and villains is a habit Mr. Miyazaki regards with suspicion. "The concept of portraying evil and then destroying it—I know this is considered mainstream, but I think it's rotten," he said. "This idea that whenever something evil happens someone particular can be blamed and punished for it, in life and in politics, it's hopeless." Like the natural world, which follows its own laws and rhythms— "it does what the hell it pleases," in Mr. Miyazaki's words—human nature is not something that can easily be explained or judged.

In the Miyazakian cosmos, minds change, as do bodies, rivers, forests, nations and everything else. Wizards turn into birds of prey; young girls are transformed overnight into 90-year-old women; greedy parents are changed into pigs; shooting stars mutate into fire demons. You can call this magic, or you can call it art. But it may just be that he reveals, in his quiet, moving, haunted pictures, the hidden senses of the word "animation," which after all means not only to set things in motion, but also, more profoundly, to bring them to life.

在许多人看来,宫崎骏是世界上最伟大的动画电影制作者。71岁时,他名下就有了二十多部故事片。对于那些坚信动画有一种特殊力量、讲述的故事具有普遍吸引力的人来说,宫崎骏就是指路明灯。皮克斯和迪士尼动画工作室的首席创意官约翰·拉塞特在总结是什么使宫崎骏成为一位“最有独创性的”电影制片人时,这样说道:“他歌颂平静的时刻。”

宫崎骏的作品往往将电脑动画和传统技法结合起来,给诸如《玩具总动员》系列、《汽车总动员》以及《飞屋环游记》等许多电影提供了灵感。

宫崎骏的创造之根既在于“漫画”,又在于“动画”(动漫书和动漫电影)。从1997年他的史诗性作品《幽灵公主》开始,他一直都在自己的电影里使用电脑制作的图像。

有意识地表现神秘感是宫崎骏艺术的核心。如果你在他的艺术世界里徜徉足够长的时间,你就会发现自己对世界的认知焕然一新,这一点和一个人长期深深沉浸在安塞尔·亚当斯、J.M.W.特纳和莫奈的艺术作品中会发生的情况一样。一段时间之后,你就会发现,某些景象足以堪称宫崎骏式的表现手法:一片起伏的草坪,上面点缀着鲜花,空中高高漂浮着的积雨云在草坪上投下阴影,一段岩石嶙峋的山麓小丘缓缓升起,伸向白雪覆盖的顶峰,还有森林边缘渐渐暗淡的光线。

某些故事同样具有典型的宫崎骏特色,特别是那些关于某个聪明而又认真的女孩与精明狡猾的老妇人设下的诡计斗智斗勇的故事,以及那些关于神秘的年轻人遭受痛苦的故事。某些主题也是如此,比如战争和其他暴力行为的灾难性和非理性,不尊重大自然的愚蠢行为,由自私、虚荣甚至善举等普通行为引发的复杂的道德问题。

作为视觉艺术家,宫崎骏既是一位恣意豪放的幻想家,又是一位严谨的自然主义者;作为故事讲述者,他所讲述的寓言故事既让人耳目一新,又给人一种说不出的古老感。他作品的奇妙感既来自于他给拥挤的青少年奇幻作品市场带来的那份新鲜和新奇感,又来自一种令人紧张的神秘离奇的熟悉感,仿佛他将深埋在集体无意识中的传说复活了。

宫崎骏的世界充满了各种奇幻的生灵。有的聪明可爱,有的迷迷糊糊,有的令人厌恶,有的令人惊悚,有的英俊潇洒,有的高贵显赫。有可爱的森林精灵,有蹦蹦跳跳的尘球,还有会说话的猫、猪、青蛙等。在电影《哈尔的移动城堡》(改编自黛安娜·温尼·琼斯的长篇小说)中,有一个多嘴多舌的火苗;在《神隐少女》中,有一个性情忧郁、沉默寡言的无脸怪物;在他导演的第一部杰作《风之谷》中,整部电影几乎被一种名叫奥姆的三叶虫形状的硕大昆虫所充斥。

宫崎骏创造的某些形象似乎可在民间传说、奇幻文学以及其他卡通作品中找到先例或者类似的形象。比如,在1992年的电影《红猪》中,以猪的形象出现的主人公是一位精神抖擞的意大利飞行员,生活在航空时代初期。我们不难想象,这位“猪”主人公在华纳兄弟的某部作品中可能会有个口吃的表兄弟,正在为搭配运动夹克而四处找裤子。但在宫崎骏创造的日益壮大的动物园里,大多数成员——包括那个大腹便便、行动迟缓、疑似猫科动物的龙猫(现已成为他的吉卜力工作室的徽标和吉祥物)——都是完全来自这位制片人自身不可思议的想象。有一次,有人问宫崎骏,在日益壮大的儿童通俗文化的世界里,他认为自己的作品地位何在。“事实是我几乎从来没有看过那些作品,”他略显疲惫地微笑着说,“我经常看的唯一的图像来自天气预报。”

宫崎骏导演身材精悍,满头白发,举止庄重之中又带有一点顽皮,但他说这话时并非轻率地开玩笑。很难想象有哪位制片人会像他那样热衷于天气。狂暴的雷雨、柔和的微风、阳光明媚的天空都是他作品中常用的重要元素,是情绪、感情和意义的载体。他所创造的怪物和动物与那些更为传统的人物动画形象——在风中飘着长发、穿着短裙、长着圆盘般大眼睛的青春期女孩,留着胡须的士兵以及满脸皱纹的干瘪老太婆——共享银幕。这些怪物和动物是宫崎骏的动画景观中不可分割的一部分,但他的电影最为显著的特点也许就是景观本身。

他的电影情节发生地往往远离现代日本空间狭促的城市,远离那些为众多动画片提供反乌托邦背景的具有未来风格的大都市。他的角色往往居住在位于山坡的小村庄或者整洁的古镇里,半木结构的房屋凌乱地坐落在鹅卵石铺就的街道两旁。这些角色各有神通,经常一飞冲天,有乘坐滑翔机的,有骑着扫把的,还有利用自身魔力的。对飞翔的艺术再现,不管是从比喻意义上还是从纯粹的视觉效果上来说,都是宫崎骏最喜欢表现的主题之一。但他喜爱向空中冒险的一个原因也许是为了提供更为美丽的大地与河流的画面,在表现这些画面时,他既运用了电影特有的精准细腻,又体现出画家那样的艺术鉴赏力。

尽管宫崎骏的电影画面让人联想起日本风景画的严谨笔法和细腻情感,但他更多地还是战后日本的“产物”,在日本风云激荡、百家争鸣的视觉文化中,他站在了艺术和商业的顶峰。虽然他的精力几乎全都投入到电影中,但他早期的创作生涯其实还包括电视卡通剧和漫画。动画片是随美国占领军一起到达日本的,自战后以来成为日本滑稽现代性的化身。同时,在宫崎骏这样的艺术家手中,动画片也成了重塑历史、保存历史的载体。

宫崎骏的电影再现了不同的社会背景,有中世纪的日本、19世纪的欧洲,还有儒勒·凡尔纳以及H·G·威尔斯创造的古老的未来,并向当今时代投以忧郁——有时也带有责备——的目光。《哈尔的移动城堡》中的反战意味和《风之谷》以及《幽灵公主》中的生态警告同样无可置疑。而且,几乎在他的每一部电影中,技术傲慢、政治野心和贪婪无度都是罪恶的真正根源。然而,他对现代世界的批判,与其说是针砭时弊,倒不如说是哲学意义上的;他的电影并不代表某种观点,而是提供了看待事物的一种方式,这种方式和我们平时所见大相径庭。

几乎无可否认的是,它们都是遁世娱乐产品的杰作,但这种遁世意义非同寻常,因为它们使人可以逃离其他现代娱乐形式中所充斥的噪音和侵害。他施展魔力的能力似乎没有止境,那些折磨、欺骗或者帮助他主人公的巫师、巫婆和魔法师与其说是他的另一个自我,倒不如说是他的近亲。但这种施展魔力的能力来自于——同时也表现出——一种同样强大的幻灭感。

严格地说,宫崎骏电影并不悲观;作为童话,他们也确实有皆大欢喜的结局。(“我不想拍出一部电影告诉孩子:‘你应该绝望、逃避,’”他说。)但是他所选择的幸福路线有可能令人感到不安,也许对美国观众来说尤为如此,因为他们认为任何情感上的主张都要建立在明确区分善恶的基础上。然而,对于将世界划分为英雄与坏蛋的做法,宫崎骏一向抱有怀疑态度。“先创造邪恶,然后再摧毁它——我知道这是主流做法,但我认为这是老掉牙的套路,”他说,“一旦发生了邪恶之事,就要责备、惩罚某个人,不管在生活中还是在政治中,这种想法都是不可救药的。”就像自然界一样遵循自身的法则和节奏一样——用宫崎骏的话来说就是“它高兴怎样就怎样”——人性也不是那么容易就能解释清楚或者下结论的。

在宫崎骏创造的世界里,身体、河流、森林、国家以及其他一切事物都会发生变化,思想也一样。巫师会变成猛禽;妙龄女郎一夜之间会变成90岁的老妪;贪婪的父母会变成猪猡;流星会变成火魔。你可以称之为魔法,你也可以称之为艺术。但他也可能只是在以不动声色的、动态的、令人欲罢不能的画面来揭示“动画”一词的深层含义:说到底,“动画”的意义不仅仅是要让物品动起来,更为深刻的是,要赋予它们生命。