We can analyze speech sounds from various perspectives and the two major areas of study are phonetics and phonology. PHONETICS studies how speech sounds are produced, transmitted, and perceived. Imagine that the speech sound is articulated by a Speaker A. It is then transmitted to and perceived by a Listener B. Consequently, a speech sound goes through a three-step process, as shown in Figure 2. 1.

Figure 2.1 The process of speech production and perception

Naturally, the study of sounds is divided into three main areas, each dealing with one part of the process:

● ARTICULATORY PHONETICS is the study of the production of speech sounds.

● ACOUSTIC PHONETICS is the study of the physical properties of speech sounds.

● PERCEPTUAL or AUDITORY PHONETICS is concerned with the perception of speech sounds.

PHONOLOGY is the study of the sound patterns and sound systems of languages. It aims to "discover the principles that govern the way sounds are organized in languages, and to explain the variations that occur" (Crystal, 1997: 162).

In phonology we normally begin by analyzing an individual language, say English, in order to determine its PHONOLOGICAL STRUCTURE, i. e. which sound units are used and how they are put together. Then we compare the properties of sound systems in different languages in order to make hypotheses about the rules that underlie the use of sounds in them, and ultimately we aim to discover the rules that underlie the sound patterns of all languages.

In this chapter, we will introduce and discuss some of the basic ideas of articulatory phonetics and phonological analysis.

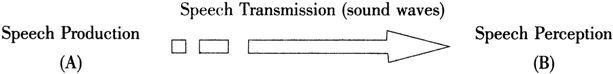

SPEECH ORGANS, also known as VOCAL ORGANS, are those parts of the human body involved in the production of speech (Figure 2.2). It is striking to see how much of the human body is involved in the production of speech: the lungs, the trachea (or windpipe), the throat, the nose, and the mouth.

The pharynx, mouth, and nose form the three cavities of the VOCAL TRACT. Speech sounds are produced with an AIRSTREAM as their sources of energy. In most circumstances, the airstream comes from the lungs. It is forced out of the lungs and then passes through the bronchioles and bronchi, a series of branching tubes, into the trachea. Then the air is modified at various points in various ways in the larynx, and in the oral and nasal cavities: the mouth and the nose are often referred to, respectively, as the ORAL CAVITY and the NASAL CAVITY.

Inside the oral cavity, we need to distinguish the tongue and various parts of the palate, while inside the throat, we have to distinguish the upper part, called PHARYNX, from the lower part, known as LARYNX. The larynx opens into a muscular tube, the pharynx, part of which can be seen in a mirror. The upper part of the pharynx connects to the oral and nasal cavities.

The contents of the mouth are very important for speech production. Starting from the front, the upper part of the mouth includes the upper lip, the upper teeth, the alveolar ridge, the hard palate, the soft palate (or the velum), and the uvula. The soft palate can be lowered to allow air to pass through the nasal cavity. When the oral cavity is at the same time blocked, a NASAL sound is produced.

The bottom part of the mouth contains the lower lip, the lower teeth, the tongue, and the mandible (i. e. the lower jaw). In phonetics, the tongue is divided into five parts: the tip, the blade, the front, the back and the root. In phonology, the corresponding sounds made with these parts of the tongue are often referred to as CORONAL (tip and blade), DORSAL (front and back) and RADICAL (root).

Figure 2.2 The organs of speech (Based on MacMahon, 1990: 7)

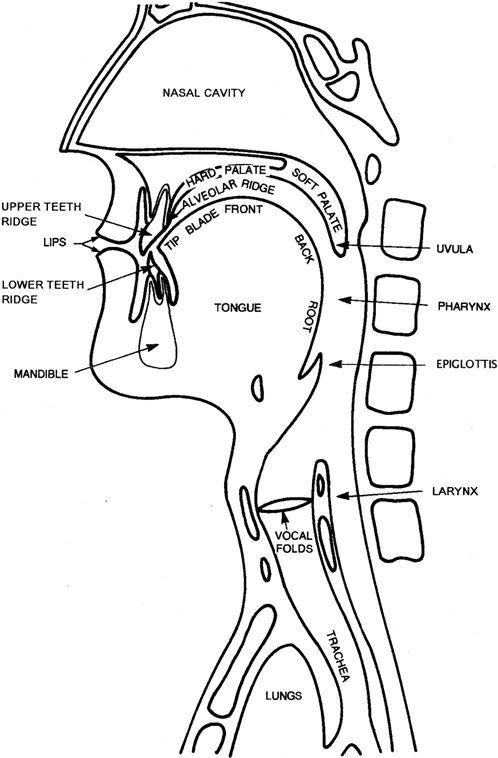

At the top of the trachea is the larynx, the front of which is protruding in males and known as the "Adam's Apple". The larynx contains the VOCAL FOLDS, also known as "vocal cords" or "vocal bands". The vocal folds (Figure 2.3) are a pair of structure that lies horizontally with their front ends joined together at the back of the Adam's Apple. Their rear ends, however, remain separated and can move into various positions.

Figure 2.3 The vocal folds (Source: Roca & Johnson, 1999: 15)

For most phonetic purposes, however, it is sufficient to say that the vocal folds are either (a) apart, (b) close together, or (c) totally closed.

● When the vocal folds are apart, the air can pass through easily and the sound produced is said to be VOICELESS. Consonants [p, s, t] are produced in this way.

● When they are close together, the airstream causes them to vibrate against each other and the resultant sound is said to be VOICED. [b, z, d] are voiced consonants.

● When they are totally closed, no air can pass between them. The result of this gesture is the glottal stop [?].

In 1886, the Phonetic Teachers' Association was inaugurated by a small group of language teachers in France who had found the practice of phonetics useful in their teaching and wished to popularize their methods. It was changed to its present title of the INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ASSOCIATION (IPA) in 1897.

One of the first activities of the Association was to produce a journal in which the contents were printed entirely in phonetic transcription. The idea of establishing a phonetic alphabet was first proposed by the Danish grammarian and phonetician Otto Jespersen (1860—1943) in 1886, and the first version of the INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ALPHABET (the IPA chart) was published in August 1888. Its main principles were that there should be a separate letter for each distinctive sound, and that the same symbol should be used for that sound in any language in which it appears. The alphabet was to consist of as many Roman alphabet letters as possible, using new letters and diacritics only when absolutely necessary. These principles continue to be followed today.

The IPA chart has been revised and corrected several times and is widely used in dictionaries and textbooks throughout the world. The latest version was revised in 2005.

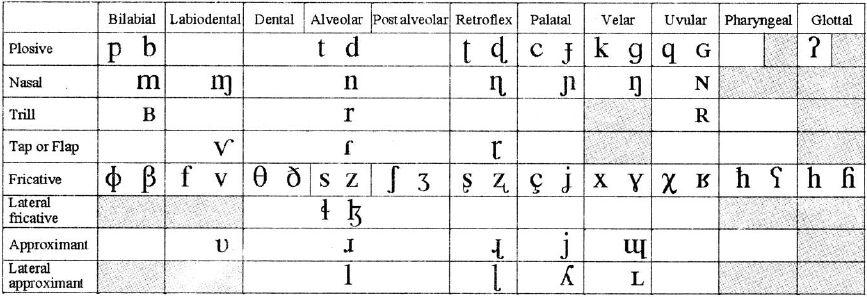

THE INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ALPHABET (revised to 2005)

CONSONANTS(PULMONIC)

2005 IPA

2005 IPA

Where symbols appear in pairs, the one to the right represents a voiced consonant. Shaded areas denote articulations judged impossible.

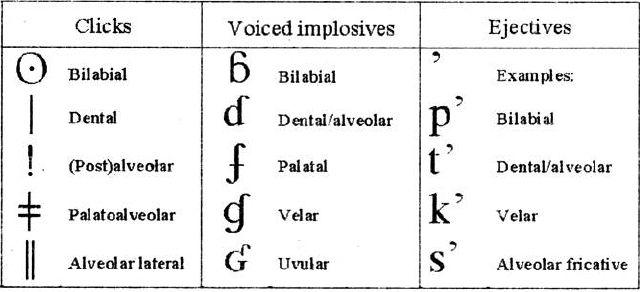

CONSONANTS (NON-PULMONIC)

OTHER SYMBOLS

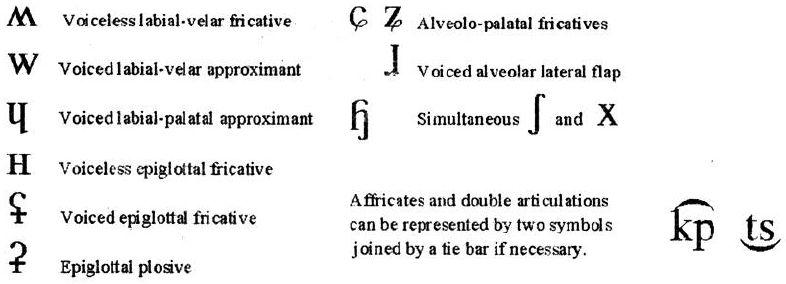

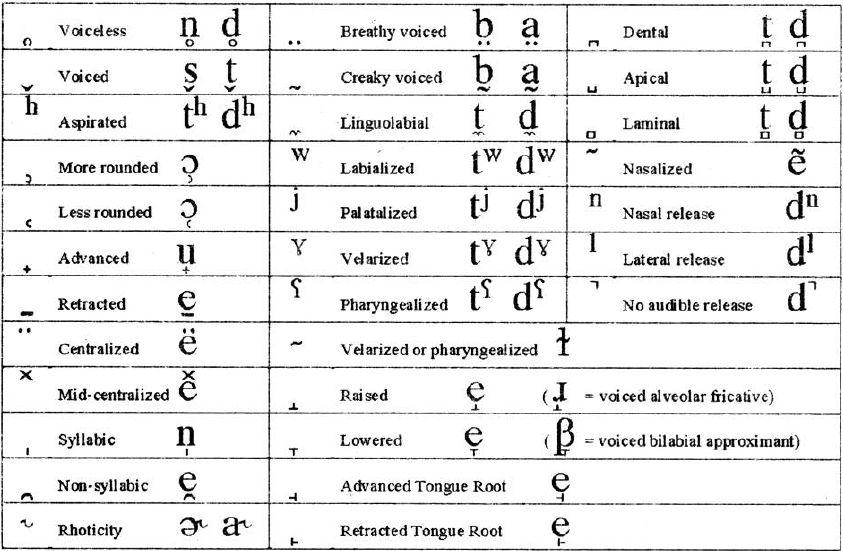

DIACRITICS Diacritics may be placed above a symbol with a descender, e. g.

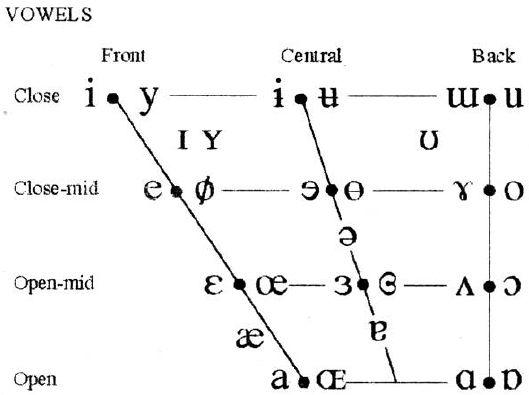

Where symbols appear in pairs, the one to the right represents a rounded vowel.

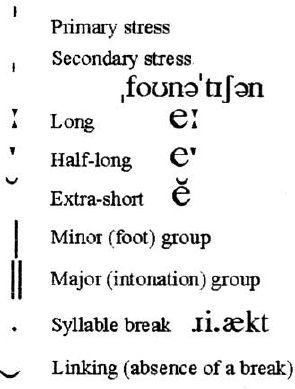

SUPRASEGMENTALS

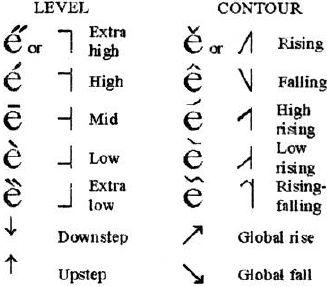

TONES AND WORD ACCENTS

In the IPA chart, the sound segments are grouped into CONSONANTS and VOWELS, which will be discussed in detail in the next section. The consonants are then divided into pulmonic and non-pulmonic consonants: PULMONIC sounds are produced by pushing air out of the lungs, as in most circumstances, while NON-PULMONIC sounds are produced by either sucking air into the mouth, in the case of clicks, or closing the glottis and manipulating the air between the glottis and a place of articulation further forward in the vocal tract, as is the case of implosives and ejectives. The vowels are shown their relevant positions in a cross-sectional diagram of the oral cavity.

The "other symbols" are actually a group of consonants that involve more than one place or manner of articulation, which cannot be placed into one of the slots in the consonant chart.

The DIACRITICS are additional symbols or marks used together with the consonant and vowel symbols to indicate nuances of change in their pronunciation. The suprasegmentals are used to represent stress and syllables, whereas the last group of symbols is used to show tonal differences and intonation patterns.

In the description of sound segments, a basic distinction is made between consonants and vowels. Consonants are produced "by a closure in the vocal tract, or by a narrowing which is so marked that air cannot escape without producing audible friction". By contrast, a vowel is produced without such "stricture" so that "air escapes in a relatively unimpeded way through the mouth or nose" (Crystal, 1997: 154). The distinction between vowels and consonants lies in the obstruction of airstream.

As there is no obstruction of air in the production of vowels, the description of the consonants and vowels cannot be done along the same lines.

In the production of consonants at least two articulators are involved. For example, the initial sound in bad involves both lips and its final segment involves the blade (or the tip) of the tongue and the alveolar ridge. The categories of consonant, therefore, are established on the basis of several factors. The most important of these factors are: (a) the actual relationship between the articulators and thus the way in which the air passes through certain parts of the vocal tract, and (b) where in the vocal tract there is approximation, narrowing, or the obstruction of air. The former is known as the Manner of Articulation and the latter as the Place of Articulation.

The MANNER OF ARTICULATION refers to ways in which articulation can be accomplished: (a) the articulators may close off the oral tract for an instant or a relatively long period; (b) they may narrow the space considerably; or (c) they may simply modify the shape of the tract by approaching each other.

(1) STOP (or PLOSIVE): Complete closure of the articulators is involved so that the airstream cannot escape through the mouth. It is essential to separate three phases in the production of a stop: (a) the closing phase, in which the articulators come together; (b) the hold or compression phase, during which air is compressed behind the closure; (c) the release phase, during which the articulators forming the obstruction come rapidly apart and the air is suddenly released. Technically this third phase is called "PLOSION", hence the name "plosive", but because of the closure involved in the production of plosives, the alternative name "stop" is frequently used to refer to this category of sounds. In English, [p, b, t, d, k, g] are stops.

(2) NASAL: If the air is stopped in the oral cavity but the soft palate is down so that it can go out through the nasal cavity, the sound produced is a NASAL STOP. Otherwise it is an ORAL STOP. Although both types of sounds are stops, phoneticians have retained the term STOP to indicate an oral stop and used the term NASAL to indicate a nasal stop. [m, n, ŋ] are nasals found in both English and Chinese.

(3) FRICATIVE: A fricative is produced when there is close approximation of two articulators so that the airstream is partially obstructed and turbulent airflow is produced. The audible friction defines this class of sounds and thus explains the label "fricative". [f, v, θ, ð, s, z, ʃ, ʒ, h] are fricatives in English.

(4) APPROXIMANT: This is an articulation in which one articulator is close to another, but without the vocal tract being narrowed to such an extent that a turbulent airstream is produced. The gap between the articulators is therefore larger than for a fricative and no turbulence (friction) is generated. In English, this class of sounds include [w, ɹ, j] ([ɹ] often represented as [r] for ease of printing although [r] is a very different sound in IPA). As [j] and [w] can also be analyzed as vowels, it is an important point to note that this category overlaps with that of vowel.

(5) LATERAL: The obstruction of the airstream is at a point along the center of the oral tract, with incomplete closure between one or both sides of the tongue and the roof of the mouth. As the lateral passage forms a stricture of open approximation, it is called "lateral". If friction is produced, it is a "lateral fricative". If no noise of friction is produced, it is a "lateral approximant". [l] is the only one lateral in English.

(6) TRILL: A trill (sometimes called ROLL) is produced when an articulator is set vibrating by the airstream. A major trill sound is [r], as in red and rye in some forms of Scottish English.

(7) TAP and FLAP: When the tongue makes a single tap against the alveolar ridge to produce only one vibration, the sound is called a tap ([ɾ]). An example of the tap is the American substitution for [t, d, n] in words such as city [sɪɾɪ] and letter [leɾɚ]. The flap ([ɽ]) is pronounced with the tip of the tongue curled up and back in a retroflex gesture and then striking the roof of the mouth in the post-alveolar region as it returns to its position behind the lower front teeth. In some forms of American English, the flap occurs in words like dirty [dɚːɽi] and sorting [sɔ̃ːɽɪŋ], after r-colored vowels in a stressed syllable (Ladefoged, 2006: 171; see 2. 2. 3 below for r-colored vowels).

(8) AFFRICATE: Affricates involve more than one of these manners of articulation in that they consist of a stop followed immediately afterwards by a fricative at the same place of articulation. In English, the "ch[tʃ]" of church and the "j[dʒ]" of jet are both affricates.

The PLACE OF ARTICULATION refers to the point where a consonant is made. Practically consonants may be produced at any place between the lips and the vocal folds. Eleven places of articulation are distinguished on the IPA chart.

(1) BILABIAL: Bilabial consonants are made with the two lips. In English, bilabial sounds include [p, b, m], as in pet, bet and met. [w], as in we and wet, involves an approximation of the two lips but is produced slightly differently: the tongue body is raised towards the velum at the same time and, for this reason, in the IPA chart it is treated as a labial-velar approximant, listed in the section of "other symbols", outside the main consonant chart.

(2) LABIODENTAL: These are made with the lower lip and the upper front teeth. [f, v], as in fire and via, are produced by raising the lower lip until it nearly touches the upper front teeth.

(3) DENTAL: Dental sounds are made by the tongue tip or blade (depending on the accent or language) and the upper front teeth. Only fricatives [θ, ð] are found to be strictly dental.

(4) ALVEOLAR: Alveolars are made with the tongue tip or blade and the alveolar ridge. Sounds produced at this place include [t, d, n, s, z, ɹ, l] for English, which is a large group of sounds.

(5) POSTALVEOLAR: These are made with the tongue tip and the back of the alveolar ridge. Such sounds include [ʃ, ʒ], as in ship and genre. This place is also known as PALATO-ALVEOLAR.

(6) RETROFLEX: Retroflex sounds are made with the tongue tip or blade curled back so that the underside of the tongue tip or blade forms a stricture with the back of the alveolar ridge or the hard palate. In Chinese Putonghua, the retroflex fricative [ʂ] is typical as in书'book' [ʂu] and事儿'thing' [ʂɚ].

(7) PALATAL: Palatal sounds are made with the front of the tongue and the hard palate. The only English sound made here is [j], as in yes and yet.

(8) VELAR: Velars are made with the back of the tongue raised to touch the velum. Examples in English are velar stops [k, g], as in cat and get, and velar nasal [ŋ], as in sing.

(9) UVULAR: Uvulars are made with the back of the tongue and the uvula. In French, the letter "r" is pronounced as the uvular fricative [ʁ], as in votre 'your'.

(10) PHARYNGEAL: Pharyngeal sounds are made with the root of the tongue and the walls of the pharynx. Arabic is a language which contains pharyngeal fricatives, [ħ,

].

].

(11) GLOTTAL: Glottal sounds are made with the two pieces of vocal folds pushed towards each other. The [h] in hat and hold is often described as a glottal fricative. The glottal stop [ʔ] is formed by bringing together the vocal folds, building up pressure behind them as for a stop and then releasing the vocal folds. Because of such a gesture, it is more of the lack of sound than a sound. A glottal stop is often perceived in words like fat [fæʔt] and pack [pæʔk], and many speakers of English have it for the "t" in words like button [bʌʔn], beaten [biːʔn], and fatten [fæʔn].

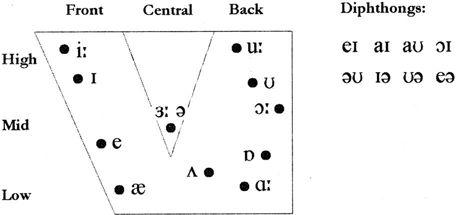

As the vowels cannot be described in the same way as the consonants, a system of cardinal vowels has been suggested to get out of this problem. The CARDINAL VOWELS, as exhibited by the vowel diagram in the IPA chart, are a set of vowel qualities arbitrarily defined, fixed and unchanging, intended to provide a frame of reference for the description of the actual vowels of existing languages.

The front, center, and back of the tongue are distinguished, as are four levels of tongue height:

● the highest position the tongue can achieve without producing audible friction (high or close);

● the lowest position the tongue can achieve (low or open); and

● two intermediate levels, dividing the intervening space into auditorily equivalent areas (mid-high or open-mid, and mid-low or close-mid). (Crystal, 1997: 155 - 156)

The system defines eight "primary" cardinal vowels, in relation to which a further set of "secondary" cardinal vowels can be defined. By convention, the eight primary cardinal vowels are numbered from one to eight as follows: CV1 [i], CV2 [e], CV3 [ɛ], CV4 [a], CV5 [ɑ], CV6 [ɔ], CV7 [o], CV8 [u]. The first five of these are unrounded vowels while CV6, CV7 and CV8 are rounded ones.

A set of secondary cardinal vowels is then obtained by reversing the liprounding for a given position: CV9 [y], CV10 [ø], CV11 [œ], CV12 [Œ], CV13 [ɒ], CV14 [ʌ], CV15 [γ], CV16 [ɯ]. Further secondary cardinal vowels can be added to the inventory: vowels which have tongue-positions halfway between [i] and [u] are represented as [ɨ] and [ʉ].

The IPA also makes available some more symbols for frequently occurring vowels, including [ɪ, ʏ, ʊ, ɘ, ɵ, ɜ,

, ɐ, ӕ]. The neutral vowel [ə] is often referred to as SCHWA. Note that by convention, where symbols appear in pairs, the one to the right represents a rounded vowel and the one to the left represents an unrounded vowel.

, ɐ, ӕ]. The neutral vowel [ə] is often referred to as SCHWA. Note that by convention, where symbols appear in pairs, the one to the right represents a rounded vowel and the one to the left represents an unrounded vowel.

Theoretically, as far as phoneticians are concerned, any segment must be either a vowel or a consonant: if a segment is not a vowel, it is a consonant. The problematic area is that the initial sound in hot gives little turbulence, depending on how forcefully it is said, and in yet and wet the initial segments are obviously vowels (MacMahon, 1990: 10; Crystal, 1997: 154 - 155). To get out of this problem, the usual solution is to say that these segments are neither vowels nor consonants but midway between the two categories. For this purpose, the term "SEMI-VOWEL" is often used.

Languages also frequently make use of a distinction between vowels where the quality remains constant throughout the articulation and those where there is an audible change of quality. The former are known as PURE or MONOPHTHONG VOWELS and the latter, VOWEL GLIDES. In the latter, if a single movement of the tongue is involved, the glides are called DIPHTHONGS. Diphthongal glides in English can be heard in such words as way [weɪ], tide [tɑɪd], how [hɑʊ], toy [tɔɪ], and toe [təʊ]. A double movement produces TRIPHTHONGS. They are really diphthongs followed by the schwa [ə], found in English words like wire [wɑɪə] and tower [tɑʊə].

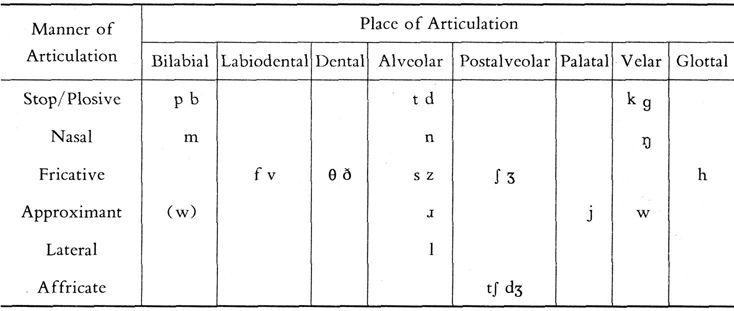

In many cases the pronunciation of English depends on individual speaker's accent and personal circumstances. Although no standard has been established on the way English should be pronounced, one form of English pronunciation is the most common model accent in the teaching of English as a foreign language. It is referred to as RECEIVED PRONUNCIATION (RP), and many people also call it BBC English, Oxford English, or King's/Queen's English. RP originates historically in the southeast of England and is spoken by the upper-middle and upper classes throughout England. It is also widely used in public schools and spoken by most newsreaders of the BBC network. In the USA, the widely accepted accent used by most educated speakers is often referred to as GENERAL AMERICAN (GA), but the differences between RP and GA in consonants are much less noticeable than those of the vowels. A chart of English consonants is given in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 A chart of English consonants

When there are two sounds that share the same place and manner of articulation, they are distinguished by VOICING, the one on the left is voiceless and the one on the right is voiced.

Now the consonants of English can be described in the following way:

[p] voiceless bilabial stop

[b] voiced bilabial stop

[s] voiceless alveolar fricative

[z] voiced alveolar fricative

When no distinction is made in voicing, only two words will be necessary. Therefore, [m] is a "bilabial nasal", [j] a "palatal approximant", and [h] a "glottal fricative". [l] may be called an "alveolar lateral" or simply a "lateral" (as in English there is only one lateral sound).

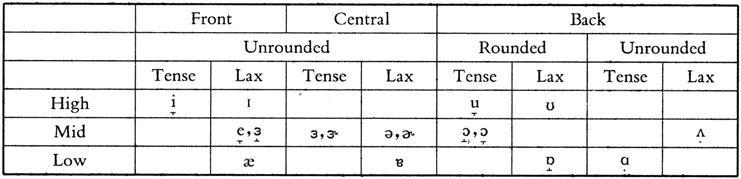

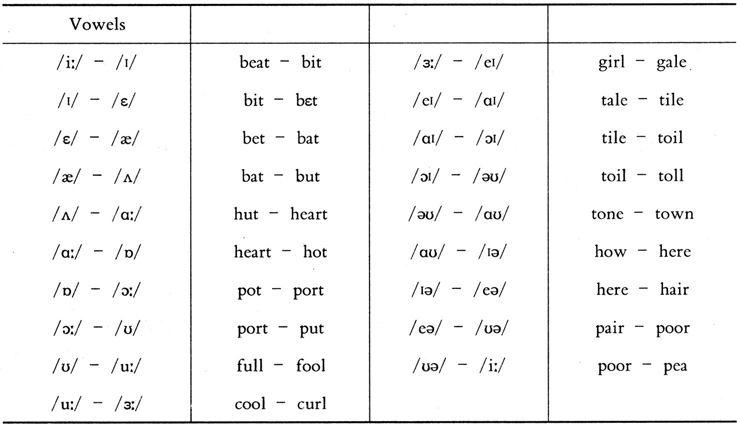

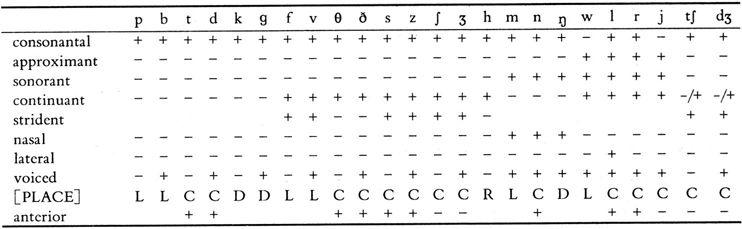

Various forms of symbols have been used for the representation of English vowels by different writers and, in this book we will follow that of Wells (2000) for the transcription of RP vowels, shown in Table 2.2. Remember that this is by no means a reproduction from the IPA chart. Instead, it is a modified version based on the IPA for making things easier.

Table 2.2 English vowels (RP)

There are certain differences between the qualities of vowels in RP and GA. Notably, the central vowels [ɜ, ə] are r-COLORED or RHOTIC for GA, transcribed as [ɝ] and [ɚ], respectively. It means that they involve curling the tip of the tongue up in a gesture of retroflection and the phenomenon is known as r-COLORING or RHOTICITY. Another major difference is that in GA [ɑ] is used where it is [ɒ] in RP, and [æ] often replaces [ɑː] in RP. Table 2.3 shows the actual RP and GA vowels, with details of their differences from the IPA vowels shown by diacritics.

Several things need to be explained here. Firstly, the idea of TENSENESS is introduced to indicate the difference between [i] and [ɪ], [ɜ] and [ə], etc. In the traditional classification of English vowels, they were said to be different in length, thus noting them as [iː] and [i], [əː] and [ə], and so on. Later, however, it was argued that they were not just different in length but they were simply different sounds. As vowels tend to be shorter before voiceless consonants, the length of [ɪ] in bid is about the same as that of [i] in beat. The difference in quality is more prominent: [i] and [ɪ] are simply different sounds, the former being pronounced with more tension. Therefore, many people simply use the different symbols to indicate the difference in quality between these pairs of sounds and ignore the length symbol [ː].

Table 2.3 Classification of RP and GA pure vowels

(Source: Roca & Johnson, 1999: 190. Note that where symbols appear in pairs, the one to the right represents the GA counterpart.)

Secondly, the low central vowel [ɐ] is often used in present-day RP for the vowel in words like but, mum or up, instead of the more traditional [ʌ]. There are also other changes in the RP, including a lower position for [æ] to the quality of CV4 [ɑ], the use of [ʌɪ] for [ɑɪ], and [ɛː] for [eə].

Thirdly, diacritics can be used to show the nuances of differences between the actual vowel qualities in English and the hypothetical vowel qualities in the cardinal vowel system. For example, the [i] in English is a little lower than CV1 and the vowel in bed is a little lower than CV2 for RP and a little higher than CV3 for GA. This explains why both [e] and [ɛ] are found in use for the phonetic transcription of English. Similarly, [ɔ] is pronounced at a slightly higher position and is more rounded in RP than in GA.

As a result, the description of English vowels needs to fulfill four basic requirements:

● the height of tongue raising (high, mid, low);

● the position of the highest part of the tongue (front, central, back);

● the length or tenseness of the vowel (tense vs. lax or long vs. short), and

● lip-rounding (rounded vs. unrounded).

We can now describe the English vowels in this way:

| [iː] | high front tense unrounded vowel |

| [u] | high back lax rounded vowel |

| [a] | mid central lax unrounded vowel |

| [ɒ] | low back lax rounded vowel |

So far we have been investigating how individual sound segments are articulated, but speech is a continuous process, so the vocal organs do not move from one sound segment to the next in a series of separate steps (Crystal, 1997: 158). Rather, sounds continually show the influence of their neighbors. For example, if a nasal consonant (such as [m]) precedes an oral vowel (such as [æ] in map), some of the nasality will carry forward so that the vowel [æ] will begin with a somewhat nasal quality. This is because in producing a nasal the soft palate is lowered to allow airflow through the nasal tract. To produce the following vowel [æ], the soft palate must move back to its normal position. Of course it takes time for the soft palate to move from its lowered position to the raised position. This process is still in progress when the articulation of [æ] has begun. Similarly, when [æ] is followed by [m], as in lamb, the velum will begin to lower itself during the articulation of [æ] so that it is ready for the following nasal.

When such simultaneous or overlapping articulations are involved, we call the process COARTICULATION. If the sound becomes more like the following sound, as in lamb, it is known as ANTICIPATORY COARTICULATION. If the sound shows the influence of the preceding sound, it is PERSEVERATIVE COARTICULATION, as is the case of map.

The fact that the vowel [æ] in lamb has some quality of the following nasal is a phenomenon we call NASALIZATION. The IPA chart contains a set of diacritics for the purpose of transcribing the minute difference between variations of the same sound. To indicate that a vowel has been nasalized, we add a curved line to the top of the symbol [æ], as [

]. By the same token, we can use these diacritics for recording other variations of the same sound. Take [P] for example, it is ASPIRATED in peak and UNASPIRATED in speak. This aspirated voiceless bilabial stop is thus indicated by the diacritic

h

, as [p

h

], whereas the unaspirated counterpart is transcribed as [p].

]. By the same token, we can use these diacritics for recording other variations of the same sound. Take [P] for example, it is ASPIRATED in peak and UNASPIRATED in speak. This aspirated voiceless bilabial stop is thus indicated by the diacritic

h

, as [p

h

], whereas the unaspirated counterpart is transcribed as [p].

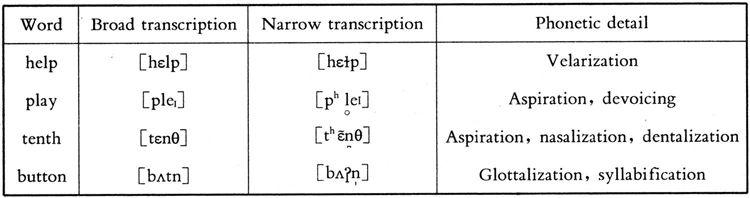

For most purposes, however, it is not necessary to indicate such variations of a sound every time. And we often use the common symbol [r] for the more unusual symbol [ɹ]. When we use a simple set of symbols in our transcription, it is called a BROAD TRANSCRIPTION. Thus the use of more specific symbols to show more phonetic detail is referred to as a narrow transcription. Both are phonetic transcriptions so we put both forms in square brackets [ ]. Compare the pairs of transcriptions in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4 Broad and narrow transcriptions of English words

Phonology is not specifically concerned with the physical properties of the speech production system. In the study of coarticulation in English, for example, it is often said that the articulation of the [t] sounds in the words tea and too differ from each other slightly. In the [t] of tea the tongue is brought towards the front of the mouth in comparison with the [t] of too, because the front vowel [iː] of tea drags the tongue slightly further forward in the mouth than the back vowel [uː] of too. In fact, it is virtually impossible to pronounce a clear and pure [iː] type vowel immediately after the kind of [t] sound found in too. Phoneticians are concerned with how these two [t]'s differ in the way they are pronounced while phonologists are interested in the patterning of such sounds and the rules that underlie such variations.

As Crystal (1997: 162) points out, "phonological analysis relies on the principle that certain sounds cause changes in the meaning of a word or phrase, whereas other sounds do not". A simple methodology to demonstrate this is to take a word, replace one sound by another, and see whether a different meaning results. For instance, the word tin in English consists of three separate sounds, each of which can be given a symbol in a phonetic transcription, [tɪn]. If we replace [t] by [d], a different word results: din. [t] and [d] are thus important sounds in English, because they enable us to distinguish tin from din, tie from die, and many more word pairs. Similarly, [iː] and [ɪ] can be shown to be important units too.

This technique, called the MINIMAL PAIRS test, can be used to find out which sound substitutions cause differences of meaning. For English, it leads to the identification of over 40 "important" units, called PHONEMES. Phonemes are transcribed with the IPA symbols, but within slant lines instead of square brackets /p/, /t/, /e/, etc. Some of the minimal pairs for English vowel phonemes are shown in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5 Some of the minimal pairs for English vowel phonemes

(Based on Crystal, 1997: 162)

The word PHONEME simply refers to a "unit of explicit sound contrast": the existence of a minimal pair automatically grants phonemic status to the sounds responsible for the contrasts (Roca & Johnson, 1999: 53). A linguistic system is built on the idea of contrasts. By selecting one type of sound instead of another we can distinguish one word from another (Spencer, 1996: 3).

Languages differ in the selection of contrastive sounds. In English, for example, the distinction between aspirated [p h ] and unaspirated [p] is not phonemic. They both belong to the same phoneme /p/ but are realized as different phonetic sounds conditioned by different positions. Compare the words peak and speak, for instance. The /p/ in peak is aspirated, phonetically transcribed as [p h ] while the /p/ in speak is unaspiratcd, phonetically [p]. In Chinese, however, the distinction between /p/ and /p h / is phonemic so that宾'guest' and拼'to piece together' are transcribed as /pin/ and /p h in/ respectively. The difference between the pinyin symbols band pis not the difference of voicing but the difference of aspiration - there is no voiced [b] in Chinese Putonghua.

By convention, PHONEMIC TRANSCRIPTIONS are placed between slant lines(/ /) while phonetic transcriptions are placed between square brackets ([ ]). In phonetic terms, phonemic transcriptions represent the "broad" transcriptions. In this sense, "broad" and "phonemic" transcriptions coincide, so there is good reason for dictionaries to use either slant lines or square brackets as they are normally phonemic and "broad". Once phonetic detail is given, however, square brackets should be used to embrace the phonetic symbols.

English dictionaries usually transcribe the words peak and speak as /pi:k/ and /spiːk/ respectively. However, when the two words are actually pronounced, we know that in English there is a rule that /p/ is unaspirated after /s/ but aspirated in other places. To bring out the "phonetic" difference, an aspirated sound is transcribed with a raised "h" after the symbol of the sound so a phonetic transcription for peak is [p h iːk] and that for speak is [spiːk].

In this example, [p, p h ] are two different PHONES and are variants of the phoneme /p/. Such variants of a phoneme are called ALLOPHONES of the same phoneme. In this case the allophones are said to be in COMPLEMENTARY DISTRIBUTION because they never occur in the same context: [p] occurs after [s] while [p h ] occurs in other places. We can represent this rule as:

(1) /p/→[P] / [s]__________

[p h ] elsewhere

(Note: "__________" is the position in which /p/ appears.)

This phenomenon of variation in the pronunciation of phonemes in different positions is called ALLOPHONY or ALLOPHONIC VARIATION. Another example of allophony in English is the phoneme /l/. We all know that it is pronounced differently in lead and deal, where in the second case the tongue is curled a little backwards towards the velum (VELARIZATION). We often call this "dark l" and use the symbol [

] in phonetic (or narrow) transcription. [l], as pronounced in lead, is called "clear l". Consequently, lead is transcribed as [liːd] and deal as [diː

] in phonetic (or narrow) transcription. [l], as pronounced in lead, is called "clear l". Consequently, lead is transcribed as [liːd] and deal as [diː

] phonetically. The rule seems very simple: the phoneme /l/ is pronounced as [l] before a vowel and as [

] phonetically. The rule seems very simple: the phoneme /l/ is pronounced as [l] before a vowel and as [

] after a vowel. They are again in complementary distribution. It can be represented as:

] after a vowel. They are again in complementary distribution. It can be represented as:

(2) /l/→ [l] /__________V

[

] / V____________

] / V____________

But things with /l/ are not so easy: in a word like telling, where there is a vowel both before and after -ll-, how do we decide whether the phoneme /l/ is pronounced as before a vowel or after a vowel? This will become clear later in this chapter, but to say that [p,p

h

] belong to the phoneme /p/ and [1,

] belong to the phoneme /l/ greatly reduces the number of phonemes in English the four sounds are attributed to only two phonemes.

] belong to the phoneme /l/ greatly reduces the number of phonemes in English the four sounds are attributed to only two phonemes.

Not all the phones in complementary distribution are considered to be allophones of the same phoneme, however. There is another restriction for phones to fall into the same phoneme: they must be phonetically similar. PHONETIC SIMILARITY means that the allophones of a phoneme must bear some phonetic resemblance. For example, [l,

] are both lateral approximants, and they only differ in places of articulation; [p, p

h

] are both voiceless bilabial stops differing only in aspiration. In either case, the allophones are both phonetically similar and in complementary distribution.

] are both lateral approximants, and they only differ in places of articulation; [p, p

h

] are both voiceless bilabial stops differing only in aspiration. In either case, the allophones are both phonetically similar and in complementary distribution.

Sometimes a phoneme may also have FREE VARIANTS. For example, the final consonant of cup may not be released by some speakers so there is no audible sound at the end of this word. In this case, it is the same word pronounced in two different ways: [k

h

ʌp

h

] and [k

h

ʌp

], with the diacritic "

], with the diacritic "

" indicating "no audible release" in IPA symbols, i. e. the sound is not actually heard. The difference may be caused by dialect or personal habit, instead of by any distribution rule. Such a phenomenon is called FREE VARIATION. Free variation is often found in regional differences. For example, most Americans pronounce the word either as [iːðɚ] whereas most British people say [aɪðə]. Individual differences may also determine the use of [dɪrɛkʃn] or [daɪrɛkʃn] for the word direction.

" indicating "no audible release" in IPA symbols, i. e. the sound is not actually heard. The difference may be caused by dialect or personal habit, instead of by any distribution rule. Such a phenomenon is called FREE VARIATION. Free variation is often found in regional differences. For example, most Americans pronounce the word either as [iːðɚ] whereas most British people say [aɪðə]. Individual differences may also determine the use of [dɪrɛkʃn] or [daɪrɛkʃn] for the word direction.

In this section we will introduce some more ideas of phonology. Let us begin by looking at the following sets of words. Consider their pronunciation in each case.

Ex. 2 - 1

| a. cap [kæp] |

can [k

n]

n]

|

| b. tap [tæp] |

tan [t

n]

n]

|

Ex. 2 - 2

| a. tent [tεnt] | tenth [tεnθ] |

| b. ninety [nainti] | ninth [naɪnθ] |

Ex. 2 - 3

| a. since [sins] | sink [sɪŋk] |

| b. mince [mɪns] | mink [mɪŋk] |

In both Ex. 2 - 1a and 2 - 1b, the words differ in two sounds. The vowel in the second word of each pair is "nasalized" because of the influence of the following nasal consonant. In Ex. 2 - 2, the nasal /n/ is "dentalized" before a dental fricative. In Ex. 2 - 3, the alveolar nasal /n/ becomes the velar nasal [ŋ] before the velar stop [k]. In this situation, NASALIZATION, DENTALIZATION, and VELARIZATION are all instances of ASSIMILATION, a process by which one sound takes on some or all the characteristics of a neighboring sound.

Assimilation is a phonological term, often used synonymously with coarticulation (2.3.1), which is more of a phonetic term. Similarly, there are two possibilities of assimilation: if a following sound is influencing a preceding sound, we call it REGRESSIVE ASSIMILATION; the converse process, in which a preceding sound is influencing a following sound, is known as PROGRESSIVE ASSIMILATION (Spencer, 1996: 47). All our examples in ex. 2 - 1~2 - 3 are instances of "regressive assimilation".

Assimilation can occur across syllable or word boundaries (Clark & Yallop, 1995: 89), as shown by the following:

Ex. 2 - 4

a. pan[ŋ]cake

b. sun[ŋ]glasses

Ex. 2 - 5

a. you can[ŋ] keep them

b. he can[ŋ] go now

Studies of English fricatives and affricates have shown that their voicing is severely influenced by the voicing of the following sound. The five pairs of English fricatives and affricates are listed in (3).

(3) f, v; θ, ð; s, z; ʃ, ʒ; tʃ, dʒ

Examples in ex. 2 - 6 show how fricatives and affricates in English may be assimilated in voicing:

Ex. 2 - 6

| a. five past | [fɑɪvpɑːst] | → | [fɑɪfpɑːst] |

| b. love to | [lʌvtə] | → | [lʌftə] |

| c. has to | [hæӕtə] | → | [hæstə] |

| d. as can be shown | [əzkənbifəun] | → | [əskənbifəun] |

| e. lose five-nil | [lu:zfɑɪvnɪl] | → | [lu:sfɑɪvnɪl] |

| f. edge to edge | [ɛdʒtəɛdʒ] | → | [ɛtʃtəɛdʒ] |

The first column of symbols shows the way these phrases are pronounced in slow or careful speech while the second column shows how they are pronounced in normal, connected speech. Investigations into other sounds reveal that DEVOICING, a process by which voiced sounds become voiceless, in such contexts does not occur with other sounds, such as stops and vowels (Spencer, 1996: 46 - 49).

These changes exhibit PHONOLOGICAL PROCESSES in which a TARGET or AFFECTED SEGMENT undergoes a structural change in certain ENVIRONMENTS or CONTEXTS. In each process the change is conditioned or triggered by a following sound or, in the case of progressive assimilation, a preceding sound.

We can represent the process by means of an arrow:

(4) /v/ → [f]

Our data have shown that this does not only apply to /v/ but also to other fricatives, like /z/ and /dʒ/. Therefore, we can make a more general rule to indicate that voiced fricatives are transformed into voiceless fricatives before voiceless segments:

(5) voiced fricative → voiceless /__________voiceless

(ibid. p.47)

This is a PHONOLOGICAL RULE. The slash (/) specifies the environment in which the change takes place. The bar (called the FOCUS BAR) indicates the position of the target segment. So the rule reads: A voiced fricative is transformed into the corresponding voiceless sound when it appears before a voiceless sound.

An interesting case is the indefinite article a/an in English. Consider the following:

Ex. 2 - 7

a. a hotel, a boy, a use, a wagon, a big man, a yellow rug, a white house

b. an apple, an honor, an orange curtain, an old lady

All the words begin with a in Ex. 2 - 7a while an is used in Ex. 2 - 7b. We know that an is used when the following word begins with a vowel sound. How do we capture this in phonological representation? We should notice that it is the lack of a consonant between vowels that requires the nasal [n] to be added to the article a. For that matter, we treat the change of a to an as an insertion of a nasal sound.Technically, this process of insertion is known as EPENTHESIS. We can formulate this rule as (with ø indicating an empty position and V a vowel):

(6) ø→ [n] / [ə]__________V

Now let us examine a more complex phenomenon. We know that in English nominal plural forms are regular in most cases. The regular plural pattern, however, is highly dependent on the phonological environment. Look at the following forms:

Ex. 2 - 8

| a. desk | [dɛsk] | desks | [dɛsks] |

| b. chair | [tʃeə] | chairs | [tʃeəz] |

| c. box | [bɒks] | boxes | [bɒksəz] |

We see that the plural suffix, -(e) s in written form, is pronounced in three different ways: [s], [z], and [əz]. If we examine more words, we find that (a) [s] is used when the preceding sound is a voiceless consonant other than /s, ʃ, tʃ/, (b) [z] occurs when the preceding sound is a vowel or a voiced consonant other than /z, ʒ, dʒ/, and (c) [əz] follows any of the following sounds: /s, z, ʃ, ʒ, tʃ, dʒ/. This group of fricatives and affricates, which often behave in the same way, is traditionally known as SIBILANTS.

Now, the three variants of the plural form in English are applied in the following fashion:

(7) a. The [s] appears after voiceless sounds.

b. The [z] appears after voiced sounds.

c. The [əz] appears after sibilants.

(Note: Voiced sounds include vowels.)

In order to bring out the rule that governs this pattern, we need to say that [z], which occurs in the most cases, is the basic form and the other two forms are derived from it. The basic form is technically known as the UNDERLYING FORM or UNDERLYING REPRESENTATION (UR). The derived form is the SURFACE FORM or SURFACE REPRESENTATION (SR). Therefore, [s] is a matter of devoicing and [əz] is a case of epenthesis. The two rules are represented as follows:

(8) /z/ → [s] / [ -voice, C]____________ (Devoicing)

(9) ø → [ə] / [ +sibilant]__________[z] (Epenthesis)

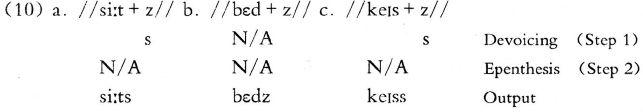

With these two rules at hand, see if we can derive the correct SRs from the URs. Consider the derivations in (10):

(Note: N/A = not applicable, where the rule does not apply.)

In Step 1 devoicing is applied, giving [s] for [siːts] for seats and [keɪss] for cases because they both end in voiceless consonants. When we come to Step 2 there is nowhere to add [ə] as neither (a) nor (c) contains a [z]-ending [z] has been changed to [s] for cases. The epenthesis rule cannot apply to [s]! Clearly, something has gone wrong. The problem is that devoicing will always apply to /z/ after a voiceless consonant and then there is never the environment for epenthesis to apply. The obvious solution is to say that epenthesis will always apply before devoicing, as in (11):

This gives us the correct surface forms. Thus, in this particular case, we have to follow a specially stipulated RULE ORDERING (Spencer, 1999: 54). If this order is disturbed, incorrect derivation will result. This rule ordering is however not always needed, as it falls to a much more general rule of language, the ELSEWHERE CONDITION, stated simply as (12):

(12) The Elsewhere Condition

The more specific rule applies first.

With the Elsewhere Condition, it is not necessary to discuss the rule ordering every time it occurs.

The idea of DISTINCTIVE FEATURES was first developed by Roman Jacobson (1896—1982) in the 1940s as a means of working out a set of phonological contrasts or oppositions to capture particular aspects of language sounds. Since then several versions have been suggested, so if you read books on phonology published at different times, expect to find different sets of features.

Some of the major distinctions include [consonantal], [sonorant], [nasal] and [voiced]. The feature [consonantal] can distinguish between consonants and vowels, so all consonants are [+ consonantal] and all vowels [- consonantal]. [sonorant] distinguishes between what we call OBSTRUENTS(stops, fricatives and affricates) and SONORANTS (all other consonants and vowels), with obstruents being [- sonorant] and others [+ sonorant]. [nasal] and [voiced] of course distinguish nasal (including nasalized) sounds and voiced sounds respectively.

These are known as BINARY FEATURES because we can group them into two categories: one with this feature and the other without. Binary features have two values or specifications denoted by "+" and "-" so voiced obstruents are marked [+ voiced] and voiceless obstruents are marked [- voiced].

The place features are not binary features they are divided up into four values: [PLACE: Labial], [PLACE: Coronal], [PLACE: Dorsal], and [PLACE: Radical], which are often written in shorthand forms as [Labial]p, [Coronal]p, [Dorsal]p, and [Radical]p.

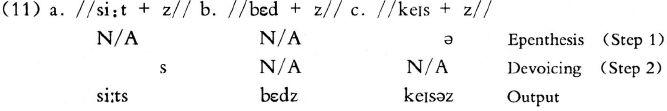

In contemporary phonology, some twenty such features are used to group speech sounds from different angles. Table 2.6 shows the feature specifications for English consonant phonemes.

Table 2.6 Distinctive feature matrix for English consonant phonemes

(Source: Radford, et al. 1999: 141. Note that 1) L = Labial, C = Coronal, D = Dorsal, R = Radical. 2) "-/+" is a special type of feature value for an affricate indicating that the sound has both specifications, one after another. 3) "anterior" is used to separate "coronal" into two further regions.)

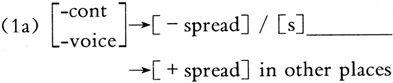

A useful feature for consonants not found in Table 2.6 is [±spread] (for "spread glottis"), which distinguishes between "aspirated" and "unaspirated" voiceless obstruents. Aspirated sounds are [+ spread] and unaspirated sounds are [- spread]. Now we can represent the rule that governs the unaspiration of /p/ after [s] in 2.3.3 (1) in terms of features, as in (1a):

This is a more general rule, which also applies to /t/ and /k/. It means that /p, t, k/ ([- voiced, - cont]) are all unaspirated ([- spread]) after [s] and aspirated ([+ spread]) in all other positions.

At this level, there is no need to know exactly what each feature value means. It will do as long as you can find out from this table what features will make a group of sounds distinct from others. Sometimes it is not possible to simply single out one phoneme as phonological rules generally will not affect only one phoneme, but a class of phonemes sharing certain features.

Let us now examine the regular past tense forms in English.

Ex. 2-9

a. stopped, walked, coughed, kissed, leashed, reached

b. stabbed, wagged, achieved, buzzed, soothed, bridged

c. steamed, stunned, pulled

d. played, flowed, studied

e. wanted, located, decided, guided

The spelling here is again very simple, with -(e) d added to the base form of the verb, but the pronunciation of these endings are different: in (a) the -ed is pronounced as [t], in (b-d) it is [d], and in (e) it is [ɪd]. We can easily recognize the rules behind these variations in pronunciation as:

(13) The regular past tense form in English is pronounced as [t] when the word ends with a voiceless consonant, [d] when it ends with a voiced sound, and [ɪd] when it ends with [t] or [d].

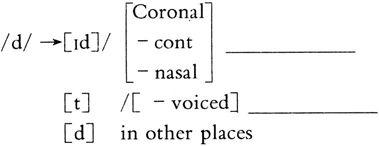

The rule can be formulated, in feature form, as:

(14) The past tense rule in English

The features [C, -cont, -nasal] are sufficient to separate [t] and [d] from all other consonants. We take /d/ as the underlying (phonemic) form because it is the mostly distributed covering all sonorants. [ɪd] is the most specific and therefore must be applied first among the three possibilities, according to the Elsewhere Condition 【1】 .

SUPRASEGMENTAL FEATURES are those aspects of speech that involve more than single sound segments. The principal suprasegmentals are stress, tone, and intonation.

The SYLLABLE is an important unit in the study of suprasegmentals. In English, a word may be MONOSYLLABIC (with one syllable, like cat and dog) or POLYSYLLABIC (with more than one syllable, like transplant or festival).

A syllable must have a NUCLEUS or PEAK, which is often the task of a vowel. However, sometimes it is also possible for a consonant to play the part of a nucleus, as in the word table, which consists of a syllable [t

h

eɪ] and a syllable

. In the second syllable there is only the syllabic consonant

. In the second syllable there is only the syllabic consonant

to function as the nucleus. Consonants [m, n] also have such functions in English, as in bottom

to function as the nucleus. Consonants [m, n] also have such functions in English, as in bottom

and cotton

and cotton

.

.

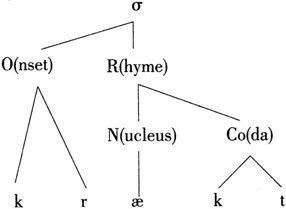

When we say that words like bed, dead, fed, head, led, red, said, thread, wed rhyme, we mean that the sounds after the first consonant or consonant cluster are identical. Therefore, we can divide a syllable into two parts, the RHYME (or RIME) and the ONSET. The vowel within the rhyme is the nucleus, with the consonant(s) after it termed the CODA. We can thus represent the SYLLABIC STRUCTURE of the word cracked in (18), with the Greek letter

("sigma") to represent a syllable.

("sigma") to represent a syllable.

(15)

All syllables must have a nucleus but not all syllables contain an onset and a coda. A syllable that has no coda is called an OPEN SYLLABLE while a syllable with coda is a CLOSED SYLLABLE.

Different languages permit different kinds of syllables. In English, the onset position may be empty or filled by a cluster of as many as three consonants, while the coda position may be filled by as many as four consonants (as in sixths [siksθs]). For this matter, the English syllable may be represented as (((C)C)C)V((((C)C)C)C). The Chinese Putonghua syllable, however, allows at most one consonant in the onset position and only nasals [n, ŋ] in the coda. Thus the Putonghua syllable is represented as (C) V (C).

No agreement has been reached as to what forms a syllable. Consequently, the division of syllables in polysyllabic words has to be solved according to some principles. One of these is the MAXIMAL ONSET PRINCIPLE (MOP), which states that when there is a choice as to where to place a consonant, it is put into the onset rather than the coda (Radford, et al., 1999: 91 - 92). This explains the question of why /l/ in telling is pronounced as [l], not [

], as discussed in 2.3.3 (2). Although there are vowels before and after -ll-, by MOP it must go with the second syllable as onset, so the pronunciation is [l] as it should be before the vowel.

], as discussed in 2.3.3 (2). Although there are vowels before and after -ll-, by MOP it must go with the second syllable as onset, so the pronunciation is [l] as it should be before the vowel.

STRESS refers to the degree of force used in producing a syllable. In transcription, a raised vertical line [ˈ] is often used just before the syllable it relates to. A basic distinction is made between stressed and unstressed syllables, the former being more prominent than the latter, which means that stress is a relative notion. At the word level, it only applies to words with at least two syllables. At the sentence level, a monosyllabic word may be said to be stressed relative to other words in the sentence.

The stress pattern in English is no easy matter (see Gimson, 2001: 224 - 235 and Roach, 2000: Chapters 10 & 11 for detailed descriptions). In principle, the stress may fall on any syllable. They also change over history and exhibit regional or dialectal differences. For example, it has been observed that in'tegral, coˈmmunal, forˈmidable and conˈtroversy are becoming the norm whereas ˈintegral, ˈcommunal, ˈformidable and ˈcontroversy are often considered conservative (Clark & Yallop, 1995: 350 - 351). Speakers of RP and those of GA also differ in their preferences in the stress pattern of these words: laˈboratory (RP), ˈlaboratory (GA); ˈdebris (RP), deˈbris (GA); ˈgarage (RP), gaˈrage (GA).

It has also been observed that stress is sometimes placed on a different syllable for the different grammatical function a word plays. For example, conˈ vict (v.) - ˈconvict (n.), inˈsult (v.) - ˈinsult (n.), proˈduce (v.) - ˈproduce (n.), reˈbel (v.) - ˈrebel (n.), reˈcord (v.) -ˈrecord (n.).

For long words, there are often two stressed syllables, one being more stressed than the other. The more stressed syllable is the primary stress, preceded by [ˈ], while the less stressed syllable is known as the secondary stress, which is indicated by a preceding symbol [ˌ]. In the word ˌepiphe ˈnomenal, for example, the primary stress falls on -no- while the secondary stress is on epi-.

Sentence stress is much more interesting. In general situations, notional words are normally stressed while structural words are unstressed. Nevertheless, sentence stress is often used to express emphasis, surprise etc. so that in principle stress may fall on any word or any syllable:

Ex. 2 - 10

a. John bought a red bicycle.

b. ˈJohn bought a red bicycle.

c. John ˈbought a red bicycle.

d. John bought a ˈred bicycle.

e. John bought a red ˈbicycle.

INTONATION involves the occurrence of recurring fall-rise patterns, each of which is used with a set of relatively consistent meanings, either on single words or on groups of words of varying length (Cruttendcn, 1997: 7). For example, the fall-rise tone in English typically involves the meaning of a contrast within a limited set of items stated explicitly or implicitly. This tone is used in all of the following examples:

Ex. 2 - 11

a. (Isn't her name Mary?) No / ν Jenny

b. The old man didn't come / whereas the ν young man / did come and actually enjoyed himself

c. ν I didn't do it

("/" indicates an intonation-group boundary and the "ν" mark indicates a fall-rise tone spread over all syllables before the next boundary.)

A difference in tone changes the meaning of a group of words and, when this happens, it is called a difference in intonation. The rising tone at the end of an utterance is often used for asking yes-no questions and showing politeness or surprise, whereas the falling tone sometimes leads to rudeness and abruptness.

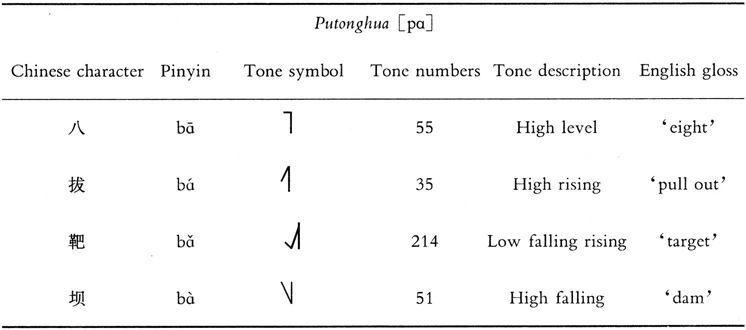

In Chinese tone changes are used in a different way, affecting the meanings of individual words. In Chinese Putonghua, a syllable such as [pɑ] can have at least four meanings depending on the tone on which it is spoken (Table 2.7). More meanings are found if we consider the different characters with the same pronunciation and tone form. Languages like Chinese are known as TONE LANGUAGES.

Table 2.7 Tones in Putonghua

In Table 2.7, the third column (tone symbol) shows the IPA tone symbol for the word, with the vertical bar at the right of the tone marking the range of the speaker's voice, and the position and shape of the line attached on its left showing the tone change during the word. The fourth column (tone numbers) shows in numbers the movement of the tone contour, with the lowest position being 1 and the highest, 5.

注 释

【1】 Note that after the Elsewhere Condition was formulated, the original expression elsewhere, as seen in 2.3.3 (1), in the final part of the rule, was changed to in other places.